Montana-Class: The U.S. Navy Battleship That Was Never Built (Mistake?)

Though they were ultimately never actually produced, the Montana-class battleships were the last battlewagons ever to be ordered by the U.S. Navy.

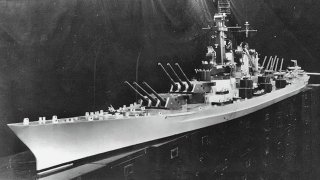

Meet the Montana-Class: Of all the battleships that served in the illustrious history of the U.S. Navy, the Iowa-class battleships are undoubtedly the most famous, thanks in no small part to two factors. They were the last battleships of any nation to fire their guns in anger, namely during Operation Desert Storm in 1991.

The Japanese surrender during WWII was hosted by an Iowa-class BB, the U.S.S. Missouri (BB-63), affectionately nicknamed “The Mighty Mo.”

But had historical fate taken a different twist, the Mighty Mo and her sister ships might have been supplanted in fame and prestige by “The Mighty Monty,” i.e. the Montana-class battleships (No pun intended with “Monty” vis-a-vis Montgomery Burns from The Simpsons, Field Marshal Bernard Law Montgomery, or the movie The Full Monty, by the way).

“A Capital Ship for an Ocean Trip…”

Though they were ultimately never actually produced, the Montana-class battleships were the last battlewagons ever to be ordered by the U.S. Navy, authorized under the “Two Ocean Navy” building program and funded in the Fiscal Year 1941. These ships were nearly a third larger than the preceding Iowa-class, at 921 feet (280.41 meters) in length and with a beam of 121 feet (36.88 meters), and a displacement of 60,500 tons—nearly 71,000 tons with full war load.

For a basis of comparison, the Imperial Japanese Navy’s (IJN) Yamato and Musashi were still slightly heavier at 72,809 tons fully laden and wider abeam at 128 feet (38.9 meters) but shorter in hull length at 862 feet (233 meters). The IJN’s super-BBs still had the biggest guns, at 18.1 inches (46 cm), as the Montanas would have retained the 16-inchers (40.64 cm) of the Iowas, but with an added twist: three extra such guns, for a dozen in total, and increased armor—21,000 tons with bulkheads at 18-inches of plating—for good measure.

A total of five of these behemoths were ordered, with the namesake in her class (BB-67) to be built at the Philadelphia Navy Yard along with the Ohio (BB-68); whilst Maine (BB-69) and New Hampshire (BB-70) were to be constructed at the New York Navy Yard in Brooklyn; and the Louisiana (BB-71) at the Norfolk Navy Yard in Portsmouth, Virginia. The Navy would eventually resurrect the Ohio moniker for its ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) class, but that’s a different story.

Although the Montanas would not have one-upped Yamato and Musashi in terms of the main gun bore size, the American’s 16-inch/50-caliber guns were indeed no slouch in terms of accuracy, power, and range, as they could lob 2,700-pound (1224.69 kg) shells over an astonishing distance of up to 23 miles (37 km).

Each gun took dozens of sailors to fire, and these dozens of sailors in turn comprised just a small fraction of the total crew complement of 2,355 enlisted sailors and commissioned officers.

The “dirty dozen” (so to speak) main guns were in turn backed up by a secondary battery of twenty 5-inch (12.7 cm)/38-caliber guns – the standard bore size for the main guns on U.S. Navy destroyers (DDs) and destroyer escorts (DEs) at the time.

Very impressive stats. So then, what killed the Montanas in their proverbial womb?

Why the Montana-Class Failed?

For starters, with all that extra firepower and bulk also came extra expense, in terms of fun and maintenance. Moreover, as noted by my 1945 colleague Brent M. Eastwood, “The Navy was also willing to roll with the punches and react to modern trends in warfare.

The airplane and the aircraft carrier proved to be more important and vital compared to the battleship. A squadron of dive bombers could menace these big ships to the point of full destruction.

Ship on ship warfare was also changing. The Navy had assumed before the war that battleships would use their decisive power to eliminate the maximum amount of enemy shipping. Enemy submarines were also always dangerous, and a launch of numerous torpedoes at once could endanger the battleship – no matter how thick the armor.”

Last but not least, the death knell of the Montana-class was sounded by its speed, or lack thereof, 28 knots compared with the 33-knot maximum speed capability of the Iowas. As 1945 colleague Peter Suciu states, this was “not fast enough to escort carriers, but still fast enough to operate in the battle line.

Given the threat of enemy aircraft, especially in how the Royal Navy’s HMS Prince of Wales and HMS Repulse were sunk off the coast of Singapore in December 1941 – less than a year after she was commissioned – by torpedo aircraft, the slower speed was an issue.” Given how these sinkings comprised arguably the single darkest day in the history of the Royal Navy, this was no mere trifling consideration for Britain’s American allies.

“I Would Like to Have Seen Montana…”

With all of those factors weighing in upon the decision, the Navy canceled the Montana program on 21 July 1943.

But had those Navy planners been in possession of a crystal ball and thus been able to foresee the Iowa-class battleships’ new leases on life as Earth-shattering shore bombardment platforms during the Korean War, Vietnam War, Lebanon, and first Iraq conflicts alike, who knows if those decision-makers might’ve changed their minds?

Christian D. Orr is a former Air Force officer, Federal law enforcement officer, and private military contractor (with assignments worked in Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, Kosovo, Japan, Germany, and the Pentagon). Chris holds a B.A. in International Relations from the University of Southern California (USC) and an M.A. in Intelligence Studies (concentration in Terrorism Studies) from American Military University (AMU). He has also been published in The Daily Torch and The Journal of Intelligence and Cyber Security.