The U.S. Military Needs To Study World War II If It Wants to Beat China in a War

The U.S. Pacific strategy was to intercept and deny the enemy's energy resources.

It makes no sense to attempt to enter a fight on Chinese terms, in their own front yard, against a massive opponent who has historically demonstrated the ability to take a great number of punches on home ground and still stay in the fight.

Military organizations are often accused of fighting the last war. In the case of the U.S. Air Force, the war in question is Desert Storm, the last unambiguous U.S. victory and a major milestone in the development of American air power.

(This first appeared in 2015.)

The Gulf War was a major success, demonstrating effective applications of stealth, precision and electronic warfare. But the war was fought with overwhelming logistical, numerical and technological superiority against an adversary that was geographically isolated, poorly trained, badly equipped and ineptly led.

It is unlikely that the United States will operate from such a position of advantage again. Pentagon planners should give up on the fantasy of a short, decisive war against the People’s Republic of China — any “short, decisive war” involving the PRC is likely to end in a PRC victory.

In a potential conflict with China, it is the U.S. that is geographically and numerically disadvantaged. Further, China has organized military developments for the past two decades around one key principle — that the U.S. would not be allowed to repeat Desert Storm.

The U.S. Department of Defense summarizes the Chinese approach under an “anti-access, area denial,” a.k.a A2AD label, but is overly focused on finding technological means to operate in the A2AD environment in order to attempt a repeat of the Gulf War’s air campaign. China is perhaps the least likely country to succumb to such a strategy, which is really an attempt to match strength against strength in an epic, mano-a-mano battle where China holds advantages in distance and mass that we are unlikely to ever overcome conventionally.

If the Air Force is going to do its part in deterring the PRC, the Pentagon must contribute to a viable offset strategy that relies as much on geography as technology. This is not to say that the United States cannot effectively fight the PRC, only that it cannot do so with a replay of techniques that proved successful more than two decades ago over Iraq.

The war the United States should base its strategy upon is another conflict in which it fought an island nation that had successfully executed an “A2AD” strategy by physically occupying much of the Asian landmass from Manchuria to Burma — to Wake Island and the Solomons.

The example we are looking for, and should be planning to, is the Pacific War from 1941 to 1945.

An analysis of the flow of goods and materials into and out of China reveals that with 98 percent of all freight moving by sea, China is practically, if not geographically, an island nation.

As such, it is vulnerable to interdiction of trade routes and energy supplies to a far greater degree than a land power, and this is a national vulnerability that air power is well-positioned to exploit — if applied properly.

Fighting Japan

The Pacific War against Japan was not a quick war. Excepting the very end, it had no “shock and awe” component. It was a grinding advance across limited real estate to approach the Japanese home islands from the south while maintaining pressure on other fronts, including the interior of China, New Guinea and the Philippines, India and Burma.

Fundamentally, it was a series of campaigns focused on establishing a logistical chain for Allied forces. That allowed the application of air power against Japan until such time as a massive amphibious assault could be undertaken or the home islands could be starved into submission.

Equally important, it was a sustained counter-logistics campaign conducted against an island nation occupying island territory across the theater.

The U.S. executed a sustained maritime interdiction campaign beginning at the outset of the war. Admittedly, it was the only option available to the U.S. Navy, but also one that had received a great deal of thought prior to the outbreak of war. Adm. Thomas Hart, commander of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet, authorized unrestricted submarine warfare before the Japanese second wave had recovered aboard its carriers following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

While air power accounted for sinking more warships; submarines and mine warfare accounted for 1,360 of the 2,117 large merchant ships sunk by U.S. forces. Despite the fact that Japan impressed captured ships into service, its merchant marine shrank continuously during the war because of relentless Allied attack.

Eventually, the Japanese merchant fleet was unable to perform its most basic functions — it could not replenish forward naval forces, move resources to Japan, supply outposts, or evacuate forces that could not be resupplied.

The maritime interdiction campaign was essentially a joint campaign intended in what we would characterize today as an A2AD environment. Land-based air was the major source of air power in the west, while carrier-based air supported island-hopping campaigns beginning in November 1943. Fifth Air Force’s first responsibility was to gain control of the air, which entailed substantive offensive and defensive components with limited fighter resources.

In 1942, 5AF bombers spent the majority of its time conducting logistics and counter-logistics, attacking Japanese maritime traffic, ports, airfields and oil refineries while moving critical supplies to New Guinea. In its efforts to prevent the Japanese from reinforcing their troops in New Guinea, 5AF routinely attacked anything that moved on the water.

While merchant ships loss statistics tell some of the story, they do not tell all of it. The official statistics only count ships of 500 tons displacement or greater used for long-haul routes. Japan supplemented its short haul supply fleet with small watercraft of less than 500 tons displacement.

5AF in particular attacked watercraft during the day, from locally-built barges to tramp steamers and small warships, sinking them quite literally in the hundreds. In sea areas beyond the routine reach of aircraft and in joint attack areas by night, PT Boats and submarines applied constant pressure.

By November 1942, Japanese naval forces in and around the Solomons ceased all offensive operations and dedicated its light forces almost entirely to resupply. By May 1943, the Imperial Japanese Navy’s abandoned its defensive perimeter around New Guinea. Japanese troops deaths on New Guinea alone exceeded 148,000, the vast majority through disease and starvation. From November 1942 until the end of the war, 5AF claimed to have sunk 1.75 million tons of enemy shipping, excluding barges and similar small craft.

In the home islands, the effects of maritime interdiction were substantial. In 1941, Japan’s industrial development was a fairly recent event. Japan began orienting the economy towards war in 1928, multiplying its heavy industrial production by 500 percent by 1940.

Defeating Japan

Japan’s industry needed to import raw materials, including and especially oil, ferro-alloys and nonferrous metals. Tokyo established strategic reserves in bauxite and oil. But attacks on shipping reduced the Japanese industrial base far below capacity.

Japan’s economy was not structured or resourced for a long war against an industrial power. By 1943, the Allies were successfully interdicting oil in part, and the flow of oil from the Dutch East Indies completely halted in April 1945.

The successful interdiction of the Indies did not completely shut off the flow of materials to Japan. Manchuria provided iron, coking coal, salt, bauxite and arable land, but did not provide significant sources of petroleum. Taiwan, a Japanese territory since 1895, provided resources including petroleum, but not nearly in sufficient quantities for wartime Japan’s needs.

Japanese centered its synthetic fuel production in China and Manchuria. By 1944, Japan had reached its peak production, with 15 plants producing 717,000 barrels of oil. Combined with domestic production in 1944 of 1.6 million barrels from the Japanese home islands, only nine percent of the annual oil demand was not subject to maritime interdiction.

For the majority of the war, Allied vessels did not carry out interdiction operations in the short water route across from Korea to Japan. The Sea of Japan had proven a particularly difficult operating area for submarines, and it was not within reach of U.S. aircraft. After the submarine USS Wahoo sank in November 1943, and no American sub re-entered the Sea of Japan until June 1945.

But in March 1945, Tinian-based B-29s began the largest aerial mining effort in history, codenamed Operation Starvation.

The U.S.’s intention was to close the Shimonoseki Strait, blockade Tokyo and Nagoya in the adjacent inland sea — and mine ports in Korea and the northern Japanese coast. At the time, the strait was Japan’s key maritime chokepoint, with 80 percent of the country’s maritime traffic passing through. Total monthly traffic consisted of 1.25 million metric tons of shipping, consisting of 20–30 ships above 500 tons and 100–200 ships below 500 tons.

Operation Starvation effectively shut down maritime traffic in targeted areas, accounting for more ships damaged or sunk during the last six months of the war than all other sources over the entire Pacific Theater combined.

The efforts to deprive Japan of needed resources were long-running and widespread. The mix of submarines, carrier aviation and land-based air power was an effective combination for conducting an extensive campaign at long ranges, in spite of enemy defenses and a lack of local basing for Allied air power.

Despite plans for an invasion of the Japanese home islands, many senior airmen felt that a combination of a maritime blockade and strategic bombing could drive Japan to surrender. In any event, the use of atomic weapons forced a rapid surrender and ended the debate.

Nevertheless, it is clear that absent any direct attack on the home islands by any means, the maritime interdiction campaign had successfully brought Japan to the brink of surrender. Like any island nation, Japan was uniquely vulnerable to the interruption of sea traffic.

Island nation

We do not think of China as an island nation. After all, it has almost double the land border of the United States and borders 13 independent countries.

But the land transportation links over these borders are extremely limited. The border terrain is unfavorable, dominated by desert, steppes, mountains and jungle. Border disputes with several countries, including Bhutan, India and Pakistan, have delayed or prevented development of transportation infrastructure along the PRC’s borders.

The total number of border “ports” along the Chinese border stands at 90, counting the newest connection to the Afghanistan border, but excluding airports. That number compares unfavorably with the 119 border crossings between the U.S. and Canada alone. The comparison is inherently unbalanced, in that the Chinese border is relatively undeveloped, while the U.S.-Canadian border has benefited from more than two centuries of continuous expansion.

The U.S. and Canadian road and rail networks are effectively linked, whereas Chinese railroads do not even share the same gauge — i.e. track width — as any of their neighbors excepting Mongolia and North Korea, and sometimes not even then. Continuous rail lines extend only into Russia, Kazakhstan, North Korea and Vietnam, requiring either bogie exchange or cargo crossloading wherever there is a gauge change.

The total cross-border Chinese cargo carried by rail in 2012 was 54.24 million metric tons, with another 64.9 million tons moved by truck. This is a fraction of comparable U.S. overland trade in that same year, where the rail systems moved 139 million tons with trucks moving 177 million tons. Roughly a fifth — 19 million tons in 2012 — of the PRC’s import flow by rail is coal mined in Mongolia.

There are only five long-haul rail lines crossing the border at all — three crossing from Siberia and two from Kazakhstan, and those lines carry more exports than imports. The primary reason for the expansion of the PRC’s rail crossings in the last five years has been to carry exports to markets rather than to import goods or resources.

The fifth line, Hunchun, has been closed for most of the last 15 years, but reopened in late 2013. In 2014, the Hunchun line moved comparatively little rail traffic, mostly coal.

While China has expanded and upgraded its border crossings in the last five years, they are limited in capacity by the infrastructure on both sides of the border. All five lines are far more limited than their U.S. counterparts, because they tend not to be double tracked — less than half of China’s rail lines are double tracked — and do not have the high height limits of U.S. trains, which can carry double-stack containers.

China’s road systems are also substantially less developed, with long distances between markets and with limited capacity compared to the U.S. interstate system. Also unlike the United States, China’s international land ports are concentrated in five locations, all rail and road-served.

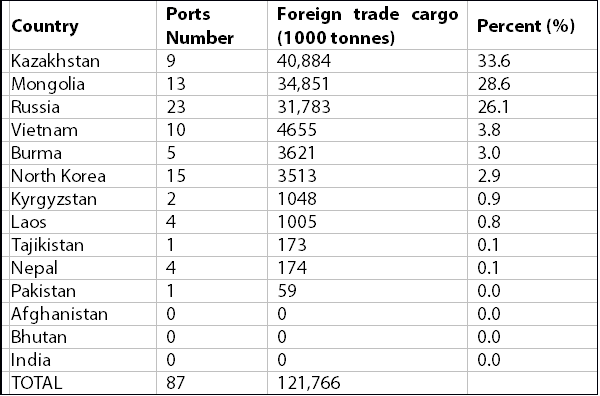

The table above shows China’s total cross-border cargo movement traffic for 2012, which includes river, road and rail traffic. Air traffic and petroleum pipelines are not included.

Notably, there were no exploitable land routes to Afghanistan (even now, the road only goes to the PRC side of the border) or Bhutan, which does not even have diplomatic relations with China. Despite the fact that China is India’s largest trading partner, the countries do not exchange goods across their disputed border.

China has three international oil pipelines, crossing from Russia, Kazakhstan and Burma. Officially, the total capacity is 980,000 barrels per day, but this number is deceptive. The largest capacity pipeline, through Burma, has yet to move more than test quantities of oil, although it has been moving natural gas.

The Sino-Burmese oil pipeline is limited by the fact that while the pipeline exists, the oil has nowhere to go once it reached the Chinese terminus in Kunming. As of this writing, China’s Kunming refinery has not been built — and there are no internal oil pipelines from Kunming to elsewhere in China.

Energy sector

China is not entirely self-sufficient in any of the non-renewable energy sources that it uses to provide electricity and transportation. As a result, China has two key vulnerabilities on the energy front.

The first is the distribution network within country, which is highly energy-intensive and largely dependent on oil. This ties together with electricity generation, in that China’s power generation capacity is mostly coal-dependent, and coal is dependent on surface transport for distribution. For 2013, coal provided 65 percent of China’s energy consumption, which has been a relatively constant figure for the last decade.

China meets 96 percent of its coal demand domestically. Chinese coal imports tend towards coking coal for industrial processes, versus steam coal for power generation. But the PRC imports the majority of its petroleum, and the maritime petroleum transport network involves long distance movement that the PRC cannot possibly protect.

As of 2014, China is the world’s second largest oil importer, approaching the United States. Throughout 2014, China averaged 6.2 million barrels per day, compared to 7.4 million for the United States. However, in February 2015, China’s oil imports spiked at an average rate of 7.53 million barrels per day, exceeding the U.S. for the month.

Driven in part by low oil prices, China fills its strategic reserves while prices are low, maintaining at least a 30-day supply of imported oil — and probably closer to 100 days.

As with coal, China’s demand exceeds domestic production, but China imports much more oil, approaching 60 percent of its total requirement.

Petroleum import data alone gives an incomplete picture of China’s fuel requirements. Crude oil is simply sticky black goo with very little utility in its unrefined state. Refining is necessary to turn that goo into useable fuels. In 2013, China’s total refining capacity was 12.6 million barrels per day, behind only the U.S. at 17.8 million barrels and representing a comfortable overcapacity of about 24 percent.

The output of China’s refineries has typically focused on lighter distillates, tending towards diesel fuel and gasoline, which allowed China to become a net diesel fuel exporter in 2012.

In 2014, driven by a strong market, Chinese major refineries switched to the more profitable middle distillates — naphtha, kerosene and jet fuel — becoming a net kerosene and jet fuel exporter and reversing a trend that hadseen China as Asia’s largest jet fuel importer only a year earlier.

This occurred despite the fact that China’s smaller, private “teakettle” refineries, which account for a quarter of the nation’s refinery capacity, produce no jet fuel components at all.

Overall, China’s expansion of its refinery capability within the past four years has left the PRC able to meet 98 percent of its demand for petroleum distillates, and capable of having a net export balance for all distillate fuels except naphtha. China’s vulnerability to supply interdiction is largely limited to crude oil, although as naphtha is a key ingredient for jet fuel, this remaining import dependency is still significant.

Maritime dependence

China’s trade across land borders is relatively low, but its sea trade is massive. Using figures from only the top 15 coastal ports, the volume of seaborne trade in 2013 came to 7.28 billion tons, up from 6.65 billion tons in 2012. Using 2012 figures, this means that international road and rail trade comes to less than 1.8 percent of the volume of freight transported by sea.

That disparity is likely to have increased in 2013 and 2014 as the amount of seaborne trade is increasing at a faster rate than any other transport mode in both relative and absolute terms.

Put another way, the annual movement of freight through all of China’s international borders is matched in under 60 days by Shanghai’s port complex alone. There is no conceivable condition under which China’s land trade routes could mitigate a maritime interdiction campaign.

The huge disparity between land and sea trade is likely to continue to increase. Overland trade is infrastructure-limited, and depends heavily on road and rail infrastructure in neighboring countries. Russia’s pipeline and rail infrastructure in Siberia has to serve multiple customers, including Russia itself, Japan and Korea.

With sea trade essentially a global phenomenon, the infrastructure is well-established and continuing to expand worldwide, without intermediate bottlenecks.

Worse for China, its naval power projection capability is limited, and the maritime geography is strategically unfavorable. The first and second island chains contrain China, putting it in a position where all of its maritime trade must pass through waterways that can fall under the control of foreign powers. China’s maritime trade generally passes through a number of chokepoints, most especially the Straits of Malacca.

Overland transport of oil via pipeline and rail accounts for less than 10 percent of all oil imports, and this only from Russia and Kazakhstan. Even Russia relies on maritime transport for oil. In 2014, 55 percent of the oil imported from Russia went by sea rather than pipeline or rail.

Looking at the rest of the totals, it’s clear that around 85 percent of the oil imported into China passes through the Straits of Malacca — 77 percent — or the Panama Canal, which comprises eight percent. Around 50 percent of the PRC’s oil imports pass through two chokepoints rather than just one — the Straits of Hormuz, the Panama Canal or Bab Al Mandar as well as Malacca.

The limits on the Strait of Malacca have a real impact on ship design, as ships too long or deep for the narrow passageway have to detour around Indonesia and sail through the Lombok Strait.

Tanker sizes have actually shrunk since the 1970s partly because of this. “Malaccamax” designs are the largest ships able to transit Malacca, and are classed a Very Large Crude Carriers. A typical VLCC can carry two million barrels of oil, but is reliant on offshore terminals or smaller tankers for loading and offloading. A single VLCC carries about four days maximum flow for the Siberian and Kazakh pipelines combined. Eleven to 15 of these vessels pass through Malacca daily, in both directions.

From a military standpoint, the majority of maritime trade is irrelevant. Container ships, which move commercial goods, constitute the majority of maritime traffic and are not militarily relevant except for spare parts and system components.

Similarly, while China imports vast quantities of raw materials, particularly iron, its domestic production of most raw materials — such as metal ores, minerals, rare earths and potash — counts it among the top three global producers, depending on the year.

In the 1930s, Japanese military expansion looked towards China’s resources as a solution to Japan’s natural resource shortages, recognizing that China is comparatively resource rich. While China cannot fuel its industrial machine with domestic products alone, it has the capacity to maintain its military industry almost entirely with domestic supplies of raw materials.

But China’s vulnerability comes from the fact that while its resources are large, the country’s massive consumption exceeds the capability of domestic resource production. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the energy sector, where Chinese demand for coal, petroleum and natural gas is satiated only through foreign imports. Indeed, it is these energy imports that could provide a key degree of leverage on the military front.

China’s power projection capabilities depend on maritime energy imports— along with the industries that produce it and the transportation networks that supply and move it.

Implications

The vast majority of China’s imports come from well outside the capability of the Chinese air force and navy to effectively protect. Unlike Japan and South Korea, which could reasonably expect to maintain northern supply routes to Alaska against Chinese opposition, the Chinese have no such geographical advantage or supporting alliance structure.

Moreover, in any conflict with China, the United States would start in a much more favorable position than it did against Japan in 1941. Washington has more combat power forward, and its partners are nations in their own right and not poorly defended colonial outposts.

China today cannot compare with Imperial Japan for amphibious sealift, and will not have a decade-long running start on territorial expansion on the Asian mainland. Certainly, America’s forward basing posture leaves U.S. forces subject to direct attack from the PRC proper, but the islands which host these bases are not under the threat of occupation.

The unfavorable maritime geography and dependency on overseas trade leaves China vulnerable to a strategic interdiction strategy — a joint effort designed to prevent the movement of resources related to military forces or operations.

In contrast with maritime interdiction, strategic interdiction is not a broad blockade but is a targeted effort to interdict primarily the production and transport of energy resources.

A campaign would have four elements.

1.) A “counterforce” effort designed to attrit the adversary air forces (particularly bombers), naval forces (gray hulls) and naval auxiliaries (replenishment) to the point where they can neither project military power nor defend against U.S. power projection, at least far beyond the PRC continental shelf.

2.) An “inshore” element, which consists of operations to deny effective use of home waters, including rivers and coastal waters. Standoff or covert aerial mining is a key component of this element.

3.) An “infrastructure degradation” plan intended to disrupt or destroy specific soft targets, such as oil terminals, oil refineries, pipelines and railway chokepoints such as tunnels and bridges. Many of these targets would be in airspace not defended by ground-based air defense.

4.) A “distant” maritime strategy, which occurs out of effective adversary military reach, intended to interdict energy supplies. This strategy is aimed primarily at bulk petroleum carriers (tankers) and secondarily at coal transports, and not at container, dry bulk or passenger vessels. Such a strategy might not be lethally oriented, directed instead towards the seizure and internment of PRC-bound vessels.

A strategic interdiction campaign is fundamentally a logistically based strategy. The primary objective is to effectively neutralize certain elements of PRC military power by starving it of energy. In effect, this strategy targets naval and air forces, which rely on jet fuel, and leaves the gasoline and diesel-dependent army to compete with domestic fuel needs — because without the PLAAF and the PLAN, the PLA cannot leave the mainland.

The primary targets are primarily air and secondarily naval forces, affecting them by an indirect route that is difficult to counter over the medium to long term.

Much has been said, with respect to PRC missile forces, that the objective is to “shoot the archer,” the implication being that such an action would prevent the archer from launching standoff weapons against air or surface targets.

An SI campaign is designed to starve the archer — the forces which protect the archer, the folks who make, carry and deliver the arrows, and the people who brought the archer to the battlefield in the first place. A complete campaign design would take advantage of the relationship between energy and infrastructure to disrupt a slice of the energy web in as many places as possible.

Such a strategy is inherently asymmetric and favors the United States, in that it cannot succeed against the American mainland. The United States’ maritime geography is extremely favorable, with four coasts that are difficult to interdict, two of which are not adjacent to the Pacific. The power projection capability required to conduct a maritime interdiction campaign against the homeland is well outside any projected PLAN capability.

The strategy also takes advantage of the U.S. advantage on blue-water naval capabilities and long-range strike aircraft. Indeed, the U.S. air power advantage is critical to any interdiction campaign, just as it was in World War II.

Against the Soviet Union, the United States elected not to undertake an approach to directly offset the Soviet advantage in numbers and the vulnerabilities of Europe to a ground invasion. Instead, it adopted offset strategies to asymmetrically counter the USSR’s strengths, leading to both tactical nuclear weapons and a revolution in precision munitions and sensors.

A quarter century after the fall of the Berlin Wall, it is perhaps time to adopt a third offset strategy aimed squarely at the PRC. For more than two decades, the standing U.S. Air Force template for applying combat air power against a target country has been the Desert Storm model. While this model may still have some applicability, it is long past time to abandon it for a conflict against a peer or near-peer nation.

The United States conducted Desert Storm against an adversary that was surrounded by enemies, outnumbered and technologically outmatched by a force with unlimited local basing, better training, leadership and equipment.

None of those conditions will apply in a conflict with China, where the United States will likely have parity in a number of these areas, a slight degree of superiority in others, and a critical disadvantage in basing, numbers and magazine depth.

It makes no sense to attempt to enter a fight on Chinese terms, in their own front yard, against a massive opponent who has historically demonstrated the ability to take a great number of punches on home ground and still stay in the fight.

The key to a successful strategy then is to maximize the potential of real, existing advantages — long range aviation, advanced naval forces and a combat-experienced enterprise — and match them against China’s import vulnerabilities, long sea lines of communication, energy requirements and unfavorable maritime geography.

With this particular set of opposing conditions, the obvious strategy template is derived from the Pacific War experience from 1941 to 1945. If the United States is going to adopt a previous strategy, it should at least be appropriate to the conditions.

This article by Michael W. Pietrucha originally appeared at War is Boring in 2015.

Image: Flickr