This Is Why A Conflict Between China and America Could Quickly Spiral Out Of Control

It's easier to start a war than end one.

Key point: China tends to only want peace on its own terms.

It’s easier to start a war than to end a war, as many a nation has learned to its cost. That’s particularly true with China. In 1937, Japan tried to conquer China: eight years later, when Japan surrendered, it was still trying. By late 1951, the Korean War had degenerated into a stalemate, and still China battled UN troops while the negotiations at Panmunjon dragged on.

So if a U.S.-China war happened today, how would it end? Once China goes to war, it may not be in a hurry for the conflict to end, according to one China expert.

“In general, China’s approach to diplomacy, escalation, and mediation created obstacles to conflict resolution,” writes Oriana Skylar Mastro, a professor of security studies at Georgetown University, in a post on the Lawfare blog.

Mastro argues that wars are more likely to end when three conditions are present: the foes are willing to talk, they are willing to de-escalate the violence to induce negotiations, and are open to third-party mediation.

The problem is that Communist China has not embraced these conditions during its previous conflicts. In terms of wartime diplomacy, “China was willing to open communication channels in the initial stages of conflict only with weaker parties,” Mastro writes. “Otherwise, China cut off communications and delayed talking until it had demonstrated sufficient toughness through fighting.”

China has also preferred to escalate rather than de-escalate in the expectation that “heavy escalation would ensure a short conflict that ended on China’s terms.” As for mediation by third parties, “because China specifically involved them to pressure the adversary on China’s behalf and not to act as genuine mediators, the Chinese internationalization of disputes did not lead to swift resolution.”

In an article in the International Studies Review, Mastro explained how the Korean War demonstrated these tendencies. China rejected negotiations during the first eight months of the war in the hopes that its armies could eject the UN forces and win the war. The massive intervention of Chinese forces reflected a belief that early and rapid escalation would convince the United States that saving South Korea would be too costly, while it also hoped that global public opinion and America’s European allies would induce the United States to leave Korea.

Given that history, Mastro believes that Beijing may be tempted to opt for rapid and heavy escalation of a regional conflict to win the war before the United States can intervene. “It isn’t when China has achieved a favorable negotiating position,” Mastro told the National Interest. “It’s when it can come to the table without looking weak for doing so, which is usually before that. They may not reach a settlement until they are in a favorable position, but they’ll talk before that if they think they can incorporate diplomacy into the strategy without hurting their war efforts.”

However, Mastro is careful to point out that “China is not the same country it was when it fought its previous wars.” China’s military is stronger than its neighbors, its economy is more integrated into the global market, and the Communist Party has less control over public opinion than Mao or Deng Xiaoping did. Indeed, increasingly nationalistic Chinese public opinion will make it tougher for China to back down.

Because China is stronger today, it may be more willing to negotiate an end to a conflict during the early stages (though Mastro notes that may not be the case in a Sino-Japanese war, where the powers are more equal). However, “the bad news is that a greater openness to wartime diplomacy does not necessarily mean China is interested in quickly and fairly settling disputes. Beijing may just want to open a channel of communication to allow its adversary to capitulate completely to its demands.”

Mastro suggests that the United States should openly indicate its willingness to talks during wartime, and offer its services as a mediator if the conflict does not involve America. The U.S. military and State Department should devise a joint political-military strategy “that takes advantage of military victories to the greatest degree possible and reduces the costs of operational setbacks.” The United States should also try to enlist the support of China’s allies such as Russia, Pakistan and Cambodia.

Ultimately, we can’t really know how today’s China will end a war until it fights a war. But Mastro paints a picture of a nation confident enough in its own power that it will only settle for peace on its own terms.

Michael Peck is a contributing writer for the National Interest. He can be found on Twitter and Facebook. This first appeared in June 2018.

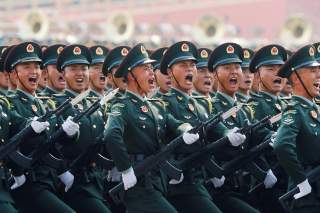

Image: Reuters.