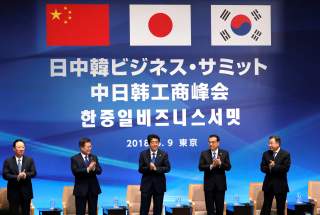

Japan and South Korea Need a "Nixon Goes to China Moment"

Moon and Abe are stubborn, but that means any deal they strike will hold better than if their political rivals were doing the negotiations.

Most of the news now about the relationship between South Korea and Japan is negative as the trade spat between the two deepens. Japan initially used a narrow trade maneuver to punish South Korea for its shifting positions on Japan’s culpability for wartime behavior in Korea. In return, Seoul hit back by creating its own trade restrictions. The South Korean government has created a whole new category of trade partners who are not reliable enough for immediate national security clearance and made Japan the only country in this category.

The rhetoric has also been tough. South Korean president Moon Jae-in has taken a very firm line. He has said South Korea will “never lose to Japan again” and that North and South Korea should cooperate to “overtake Japan.” The deep, ideological resentment for Japan on the South Korean left particularly—Moon is from the liberal party—is now exploding all over television and public spaces. I went to the Busan beach two weeks ago, and there were even anti-Japan placards dug into the sand with kids playing among them.

In Japan, there has been a similar hardening. Public opinion has swung behind Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s tough stance. Even the left-wing media, which has been far more honest about Japan’s violent wartime behavior in Korea and China, is quiet. “Korea fatigue”—the perception that South Korea purposefully will not let go of wartime issues and focus on the future—has long been an issue on the Japanese right. That seems to be spreading now.

So it increasingly looks like things will get worse before they get better. It appears that the trade war will likely drag on until the end of the year at least. Japan’s conservative government is pretty clearly exhausted with South Korea. It does not want to keep re-litigating the war, and it has chosen an unexpected and apparently rather effective leverage point. The South Korean response has been full-throated nationalism. Moon suggested North-South “peace economy” to actively compete against Japan, a move which would jeopardize the South Korean relationship with the United States if Moon were to truly act on it.

But this kind of fracture may well have been inevitable and something which the two sides need to get out of their systems. This is likely why the United States has been so quiet on the spat. In the past, Washington sought to mediate or tamp down these fights. At one point, former President Barack Obama personally intervened to bring Abe and then-South Korean President Park Geun-hye together.

The logic was always that both sides would find it politically easier to make concessions to Washington than to each other. (U.S. efforts to mediate the Israeli-Palestinian tangle are premised on similar logic.) Unfortunately, the actual outcome was stasis and irresolution. Because America insured both sides against the consequences of intransigence, neither side moved in a serious way. Issues were papered over, left to fester or worsen, and nationalist maximalists on both sides were allowed to run amok. (The films produced in both countries in the last decade or so nicely illustrates this last point.)

So this time around, the United States is stepping back. Washington’s past management failed and the flare-ups keep recurring. America’s position seems to be that it is now time for the two to work this out on their own. And U.S. Track II commentary has been broadly supportive of that Trump administration position. There is no wave of papers, op-eds, tweets, and so on this time demanding U.S. mediation. Everyone is burned out and want both countries to resolve their dispute themselves.

At this point, this is almost certainly a prerequisite for progress, and it perversely helps that Moon represents the most anti-Japanese elements in South Korea and Abe the most “Korea fatigued” faction in Japan. Deals between the South Korean right and the Japanese left will always be suspect to maximalists back home. The only way this will be resolved in a durable way is if the nationalists see themselves in the leadership, and then that trusted leadership makes concessions nonetheless.

This is, famously, the logic behind President Richard Nixon’s opening of Red China in the 1970s. Had his Democratic opponents done it, they would have been pilloried as communist sympathizers. Nixon’s anti-communist credentials gave him enough credibility with the American right to pull off a move like this. Similarly, the veteran and tough leader Charles de Gaulle was able to extract France from Algeria in the 1960s. De Gaulle was unable to control his right flank as well as Nixon—there were army rebellions and assassination attempts on de Gaulle—but had has socialist opponents tried it, there may well have been civil strife.

Moon and Abe are in the same position. They represent the most recalcitrant, stubborn elements in their societies, the constituencies which must be brought along if any final deal between South Korea and Japan is going to hold over time. For example, the South Korean right brokered a deal Japan in 2015 over wartime issues and the South Korean left broke it as soon as it took back the presidency.

The stage is now set for these two to slug it out initially: to let out all the primal nationalist anger, unhindered by external actors (America) or internal opposition (softer, conciliatory domestic groups). So this will get worse before it gets better, but it probably has to. And then, after all the screaming, exertion, and maximalism is revealed to just make things worse, the political space for durable softening will emerge. After three decades of these spats and almost no movement through conciliation, a painful collision is likely the only way to back off the maximalists and make room for a “Nixon goes to China” moment.

Robert E. Kelly is a professor of international relations in the Department of Political Science and Diplomacy at Pusan National University. More of his work may be found at his website,AsianSecurityBlog.wordpress.com.

Image: Reuters