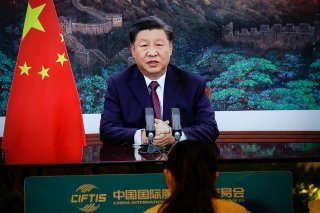

Xi Jinping's Coercive China Strategy Is Creating More Enemies Than Friends

Whatever Xi thinks he’s doing, the outcome is, on the face of it, disastrous for China’s long-term strategic interests.

What is China trying to achieve by its sudden lurch to a bullying, ‘wolf warrior’ global stance? For all the billions of dollars of intelligence hardware and software pointed at Beijing right now, the reality is that Xi Jinping’s strategic thinking is a black box.

The leadership intent of the Chinese Communist Party must be glimpsed through opaque speeches, the coded signals of coercive behaviour and the increasingly unhinged statements of China’s diplomats and party-controlled media.

Whatever Xi thinks he’s doing, the outcome is, on the face of it, disastrous for China’s long-term strategic interests. China has never had many, or indeed any, close friends internationally, but in less than a year the wolf warriors have irretrievably trashed whatever trust Beijing may have had as a trading, investment and research partner around the world.

This is a remarkable achievement. In a divided America, opposition to China is the one policy uniting Republicans and Democrats. Beijing’s bad behaviour has produced a consensus in the European Union and Britain to push back, has given ASEAN a stronger common purpose and has ignited in Australia a determination to ‘step up’ in the Pacific and spend more on defence.

Here’s one measure of how quickly and dramatically things have changed: on 20 January this year, John Howard chaired the ‘sixth annual Australia–China High Level Dialogue’ sponsored by the Foreign Affairs Department, whose press release claimed that ‘the Dialogue will help strengthen partnerships and friendships, maintain trust, and develop deeper understanding between Australia and China’.

Eight months later, not one word of that sentence could be applied to our relationship with China. Even China’s rusted-on Australian cheer squad is losing vigour in claiming that it’s Canberra’s lack of pragmatic wordsmithing that is causing the rift.

Had China continued down the Deng Xiaoping–mandated path of ‘Hide your capacities, bide your time’, I’m no longer sure that Australia would have been able to muster the collective willpower to prevent the wholesale compromising of our economy, political system, critical infrastructure, universities and business community—such was the attraction of Chinese money.

In reality, Covid-19 and wolf-warrior coercion were the wake-up call we needed, but that still leaves the essential puzzle about why it is that Beijing abandoned a strategy that was delivering its objectives and replaced it with an approach that is damaging its position.

I suggest that three broad factors are shaping Xi’s strategic thinking. Understanding these factors will help us define our policy responses and anticipate what happens next.

The first factor is that CCP policymaking is increasingly centred on one person—Xi Jinping. Through regular purges of the party and the People’s Liberation Army since 2012, Xi has removed political opponents, made himself the commander-in-chief of the military and the central driver of policy in every area from the South China Sea to the Belt and Road Initiative to the pandemic response.

If there is a centre of coordinated opposition to Xi’s policy inside the party, it is not readily visible. What is known as the ‘recentralisation’ of authority within the CCP is turning into a cult of personality around Xi.

There are clear dangers in such an approach. What senior party figure would or could approach Xi to tell him that the wolf-warrior tactic is damaging the party’s global interests? The most likely result would be that an internal critic would be purged from any position of influence.

Xi’s political instincts have been honed by his own experience of seeing his father, Xi Zhongxun, a heroic figure in the early history of the CCP, persecuted and jailed during the Cultural Revolution in the 1960s. Xi was himself exiled to a rural province at that time.

It is tempting to think that Xi’s authoritarian style is partly motivated by a determination not to be purged like his father. His leadership is also informed by deep ideological schooling in Marxist–Leninist ideology—a reality too easily dismissed in the West.

Xi has, in effect, brought Leninist authoritarianism into the 21st-century world of artificial intelligence and all-seeing surveillance. Having embarked on a path to consolidate all power to himself, it is difficult to see how Xi can break from his current course of action. In effect, that means China’s more assertive and uncompromising approach in the world will be here for as long as Xi remains in power.

The second factor shaping Xi’s approach is that, overwhelmingly, what matters to him is strengthening the position of the CCP inside China. How the wider world reacts to Beijing’s actions is vastly less important.

This helps to explain why China really has no interest in negative international responses to the militarisation and de facto annexation of the South China Sea; the trashing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration on Hong Kong; or the egregious human rights violations in Xinjiang, Tibet and elsewhere.

What matters most to the party is how its actions are perceived by the Chinese people. Asserting control over these areas plays well to a highly nationalistic domestic audience.

Beijing’s increasingly inflammatory rhetoric about defeating ‘separatism’ in Taiwan, by use of military force if necessary, may be seen by the wider world to be destabilising Asian security, but inside China it rallies popular support around the party.

At a time when the CCP is being criticised domestically for its mismanagement of the early stages of Covid-19 and is failing to deliver economic growth to achieve better living standards, stoking nationalist sentiment helps consolidate party control.

To China’s leaders, a second-order player like Australia should, ideally, just shut up. As foreign minister Yang Jiechi dismissively told his Singaporean counterpart in 2010: ‘China is a big country and other countries are small countries, and that’s just a fact.’

This combination of an overwhelming priority on domestic affairs and a barely disguised contempt for the opinions of ‘small countries’ leaves Beijing angry and frustrated at the audacity of other nations wanting to pursue their own interests.

One example of this mindset in operation is Beijing’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ claim that Australia engaged in ‘blatant obstruction and interference in China’s normal law enforcement’, by bringing journalists Bill Birtles and Mike Smith home last week.

Let’s be clear: Birtles and Smith weren’t smuggled out of the country; they left on a commercial flight after being questioned by local police. But how dare a small country question the CCP’s right to snatch people off the streets, hold them indefinitely without charge and put them before a legal system thoroughly beholden to party priorities.

The point for Australia is simply that, short of complete capitulation of our interests and values, there is nothing Canberra can do or say that will avoid China’s criticism.

This needs to be understood by elements of the Australian business and university sectors that persist in thinking Beijing’s behaviour is somehow the result of our actions—like the claim by one commentator in The Australian last week that China is ‘ruthlessly exploited’ because we are forcing them ‘to pay exorbitant prices for iron ore’. Seriously? So much for supply and demand.

There is one exception to the claim that no external power is more important to China than Beijing’s domestic priorities and that is, of course, the United States. What America does matters profoundly to China, not least because for perhaps the next five to 10 years the US retains the military balance of power.

Much of China’s international behaviour is shaped by judgements of how America will react. In the case of the South China Sea, once it became clear to Beijing that the Obama administration wasn’t going to actively oppose its island building, the opposition of Southeast Asia, Australia and other countries was immaterial.

In that context, the most important potential flashpoint to watch in coming months is Taiwan, and specifically whether Washington has any appetite to prevent China’s efforts to isolate and predate Taipei.

The third factor shaping China’s switch to the wolf-warrior approach is that Xi has concluded that coercion works. Research published by ASPI last week identified 152 cases of Chinese coercive diplomacy over the past decade applied to 27 countries and many businesses.

The actions China was seeking to punish or deter included engaging with Taiwan in ways not approved by Beijing, holding meetings with the Dalai Lama, blocking Huawei’s 5G technology and seeking investigations into the Chinese origins of Covid-19.

In many cases, and particularly in instances when Beijing was threatening businesses, the reality is that the coercion worked.

The lesson for Beijing is that access to its economy is a powerful lever for countries and businesses alike and threats to constrain access to the Chinese market can indeed force changes to behaviour that benefit China.

The lesson for Australia and all democracies is that making concessions to Beijing’s wolf-warrior behaviours will only encourage more coercion.

In my assessment, this undermines the argument that Australia should somehow try to plot a ‘middle course’ between the US and China. Beijing’s current approach doesn’t leave room for the possibility that countries can shape a course that is in any way different from China’s definition of what the right behaviour should be.

Based on this assessment of Chinese strategic motivations, it is highly likely that Beijing’s more assertive approach will continue if Xi stays in office. That is going to hurt Australia, but the only mitigation is to reduce our economic dependence on China.

It is desperately important for Australian interests that whoever is the American president after November, the US sets down a set of clear red lines on Chinese behaviour on Taiwan and Asian security more widely.

Finally, Australia needs to keep accelerating the pace of our own military plans, especially adding to our deterrent capacity with sufficient hitting power to raise the costs and challenges for any potential aggressor that might wish to do us harm.

Peter Jennings is the executive director of ASPI and a former deputy secretary for strategy in the Department of Defence. A version of this article was published in the Weekend Australian.

This article first appeared at the Australian Strategic Policy Institute.

Image: Reuters.