How Germany's World War I Stormtroopers Became Human Tanks

Could this have won the war for the Kaiser?

The word "stormtrooper" has a funny reputation. It conjures memories of brownshirted Nazi thugs terrorizing Jews, or images of Darth Vader's white-armored henchmen in Star Wars.

But in 1918, stormtroopers were Germany's human equivalent of the tank. A two-legged weapon that almost brought victory to Germany in World War I.

The origins of the stormtroopers, or stosstruppen (assault troops), began in the trench warfare of World War I. Within months after the war began in August 1914, the Western Front had fossilized into 450 miles of trenches stretching from the Belgian coast to the Swiss border.

No matter, said the generals. Our glorious infantry will smash through them with a bayonet charge. But the PBI (Poor Bloody Infantry) soon realized they were mere sheep for the slaughter against machine guns and barbed wire.

No matter, said the generals. We shall simply annihilate the enemy with a massive artillery barrage -- as in the 1.5 million shells that preceded the British 1916 Somme offensive -- and then the infantry shall merely have to stroll forward to occupy the ground. Instead, the enemy waited in their underground dugouts until the barrage lifted before emerging to mow down the attacking infantry.

After a while, the Western Front had degenerated into a mere struggle for attrition, the most futile form of warfare. Strategy at bloodbaths like Verdun consisted of flinging enough firepower to kill more of the enemy than they killed of you. Mahatma Gandhi may have been a pacifist, but he understood the problem better than the military professionals when he said "an eye for an eye leaves the whole world blind."

By 1917, with both sides running low on manpower and in national willingness to sacrifice their men, a better way was needed. Some method that would break the deadlock before the combatants attrited each other into national extinction.

Fortunately, while war is horrible, it is also dynamic. Stalemates are eventually broken, either because one side gives up, both sides make peace, or a military solution is found. In 1917-18, both the Allies and Germans found a way to break out of the stranglehold of trench warfare.

For the Allies, the solution was technological. The tank was invented as a trench-buster, a mechanical fortress that could survive passage across No Man's Land between the opposing lines. Its armor allowed it to shrug off bullets and shrapnel, its weapons could knock out German machine gun nests before the machine guns knocked off the Allied infantry, while its internal combustion engine carried that firepower and armor to the enemy's door. Given Allied superiority in natural resources and industry, it was a logical solution.

Imperial Germany had no such luxury. Outnumbered in manpower and industrial potential, worn down by years of war against a numerically superior opponent, the Kaiser's army couldn't hope to beat the Allies in what the Germans dreaded as a materialschlacht (a war of material).

The solution was the stormtrooper.

Instead of brute force or technology, German storm tactics relied on brainpower. Rather than hitting the enemy trenches head-on as in previous First World War battles, the idea was to find weak points in his line and penetrate those soft spots. Don't expend blood and time assaulting enemy strong points, said German doctrine. Bypass them and cut them off from their headquarters and supply depots. Seep into the enemy's rear and overrun his artillery batteries and command posts. By the time the defender realizes what is happening on, his front-line troops will be surrounded and isolated, to be mopped up later by follow-up waves of regular German troops.

If this sounds familiar, it's because this is exactly how blitzkrieg operated in World War II. Rommel, Patton and Zhukov would have understood the German approach very well.

Storm tactics were championed by General Oskar von Hutier, an army commander battling Tsarist Russia on the Eastern Front. Hutier envisioned an offensive beginning with an artillery barrage intensive enough to paralyze the defenders, but short enough to avoid giving them too much warning to bring up reserves. The barrage would comprise poison gas as well as high-explosive shells to stun the enemy as well as force them to don cumbersome gas masks.

Advancing behind a creeping artillery barrage that would keep landing just ahead of the German troops, the stosstruppen would cross No Man's Land in dispersed small units rather than massed targets. Heavily armed with light machine guns, mortars and the newly invented flamethrower, they would penetrate between strong points and continue into the rear areas.

A trial run came in October 1917 on the Italian front, where Austria-Hungary and Italy were mired in a bloody campaign of mountain warfare in the Alps. But at the Battle of Caparetto, German stormtroopers and infiltration tactics enabled a German-Austrian offensive to capture 265,000 Italians and nearly knock Italy out of the war.

More was to come. Since the beginning of the war, Germany had been forced to split its forces between East and West. But the fall of the Tsar, which led to the Bolsheviks pulling Russia out of the war, enabled Germany to transfer nearly 50 divisions from the East to the West in 1918. For the first time in a while, the Germans outnumbered the Anglo-French armies, but not for long: America had entered the war, and soon 2 million fresh, healthy men would arrive in France.

But even with numerical superiority, what could Germany do? Another "big push," with infantry and artillery, would only gain a couple of miles of territory at a ferocious price. But the stosstruppen offered a chance for that rarest of World War I outcomes: a breakthrough.

Fortunately for the Germans, the Allies made their task easier. The way to defend against infiltration, as against blitzkrieg mechanized offensives in the next war, was defense in depth. Multiple defensive lines could wear down and blunt an enemy attack. The way to survive massive bombardment, as Hitler's troops learned at the hands of Soviet artillery, was to leave just a few troops in the front lines and keep the bulk further to the rear to escape the barrage and then counterattack.

But unaware -- or disregarding warning of -- German infiltration tactics, the British Fifth Army packed its forward trenches with troops while their strong points were placed so far apart that they couldn't cover the gaps in between.

Sure enough, the Kaiserschlacht (Kaiser's battle), Germany's spring 1918 offensive, began with a hurricane barrage of high-explosive and gas shells that devastated the crowded British forward trenches. Cloaked by smoke, gas and fog, Stosstruppen infiltrated between the British strong points and cut off the dazed defenders.

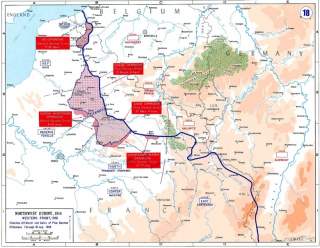

The Kaiserschlacht began with Operation Michael on March 21, 1918. Whereas the British and French had spent hundreds of thousands of men and several months to advance a mile or two, the Germans penetrated 40 miles in two weeks. The Allies, long accustomed to static combat, now found themselves in mobile warfare for the first time since the opening battles of 1914.

Between March and June 1918, Germany launched four offensives. At first they succeeded so well that the British commander, Field Marshal Douglas Haig, warned his troops that their "backs are to the wall." Yet by the end, it was the Germans who had lost.

One reason was poor German strategy; instead of aiming for key British supply ports on the coast, it attacked further inland. Worse yet, the Germans discovered that no matter how deeply they punched through Allied defenses, supplies and reinforcements trudging through a moonscape of shell craters could never keep up with the assault spearheads.

But most of all, after four years of attrition, Germany only had a limited supply of fit young men with the stamina and energy for infiltration tactics. Once that supply of energetic manpower was consumed, the tired, older men who made up the regular German army were no substitute. The Allies, on the other hand, had thousands of tanks. By November 1918, the German army could not resist Allied combined arms offensives of tanks, infantry and artillery.

Do the stosstruppen offer lessons for today? The most obvious is one that has eluded the U.S. military since the Civil War: clever tactics are a match for superior weapons and technology. It's a lesson that the Viet Cong and the Taliban have taken to heart, and one that the Chinese and Russians will utilize as well.

Yet before we toast the triumph of the human spirit, let us remember that stormtroopers didn't save Imperial Germany. The Allies could always build more tanks. The Germans, despite later Nazi visions of Aryan stud farms, couldn't suddenly hatch more 18-year-old stormtroopers like so many eggs. Perhaps there is something distasteful and unheroic about waging war through drones. But most soldiers standing in a muddy trench in 1918 would have been more than happy to let a machine do the dangerous work.

Technology alone doesn't win wars. But it's better to shed machines than blood.

Michael Peck is a contributing writer for the National Interest. He can be found on Twitter and Facebook.

Image: Map of the final German offensives on the Western Front, 1918. Wikimedia Commons/Public domain