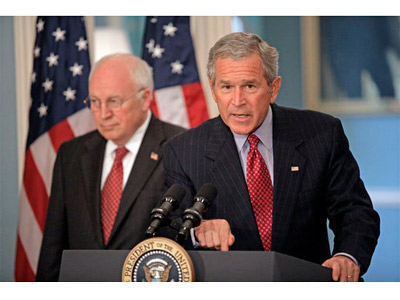

Misunderestimating Bush and Cheney

Mini Teaser: George W. was no puppet of his Vice President—and for better or worse, we're still living in the world he built.

Peter Baker, Days of Fire: Bush and Cheney in the White House (New York: Doubleday, 2013), 816 pp., $35.00.

A SPECTER is haunting Washington—the specter of George W. Bush. President Obama may have spent almost five years in the White House by now, but it’s still possible to detect the furtive presence of a certain restless shade lurking in the dimmer corners of the federal mansion. Needless to say, this is something of a first: usually U.S. presidents have to die before they can join the illustrious corps of Washington ghosts, and 43 is, of course, still very much alive in his tony Dallas neighborhood, by all accounts enthusiastically pursuing his new avocation as an amateur painter. Yet his spirit is proving remarkably hard to exorcise.

Anyone who doubts this need only consider the current debate about how to deal with Bashar al-Assad. The pollsters and the pundits have found a remarkably stubborn public consensus against the use of force, and the reasons for this reluctance invariably circle back to the case of a previous Baathist dictator who stood accused of using weapons of mass destruction against his own citizens. America’s war against Saddam Hussein may be history, but for once the American people’s notoriously flabby short-term memory has not failed them. They have distinctly little appetite for anything that looks like a redo.

So how could George W. Bush, of all people, have created such a potent legacy? As New York Times White House correspondent Peter Baker reminds us in his magisterial new book Days of Fire, Bush left office as one of the most unpopular presidents of modern times. The Iraq War was clearly the signal failure of his presidency—a point now conceded even by many of his erstwhile supporters. But that’s just the first item in the index of errors. What about the shameful embrace of torture as a principle of the so-called global war on terror? The bewildering insouciance toward the war in Afghanistan? The self-destructive contempt for America’s allies? The fumbling response to the Katrina disaster? The policies that paved the way for the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression?

Given this list of cock-ups, it would have been understandable if Baker had chosen to structure his narrative as an 816-page affidavit for the prosecution. There are still plenty of short-fused Bushophobes out there, so a hatchet job might have made for great sales. But that would also be bad history. For better or for worse, we—and President Obama most of all—still live in the world that Bush built.

Think about it. The prison at Guantánamo Bay still operates. The drone war goes on—the current president, indeed, has expanded it far beyond Bush’s wildest imaginings. As for the National Security Agency’s vast warrantless-surveillance schemes set up in the years after 9/11, the current White House hasn’t missed a beat there, either. Indeed, despite Obama’s promises to guarantee government transparency and protect whistle-blowers, his White House has gone after leakers with a ferocity that puts George W. to shame. (The current administration has brought charges against seven people under the World War I–era Espionage Act; the previous White House prosecuted only one.)

So could one, indeed, argue that the Bush presidency produced anything positive? In his efforts to provide balance, Baker does his best to make the case for Bush and Dick Cheney. He argues that this duo

accomplished significant things. They lifted a nation wounded by sneak attack on September 11, 2001, and safeguarded it from further assault, putting in place a new national security architecture for a dangerous era that would endure after they left office. At home, they instituted sweeping changes in education, health care, and taxes while heading off another Great Depression and the collapse of the storied auto industry. Abroad, they liberated fifty million people from despotic governments in the Middle East and central Asia, gave voice to the aspirations of democracy around the world, and helped turn the tide against a killer disease in Africa. They confronted crisis after crisis, not just a single “day of fire” on that bright morning in September, but days of fire over eight years.

Baker’s effort to illuminate these aspects of the story won’t make him any friends on the left. Far from it. But, again, the continuities are difficult to deny. The newly elected Obama happily continued the economic emergency measures instituted by Bush in the waning days of his term. The Troubled Asset Relief Program and the bailout for the U.S. automotive industry—some of the most far-reaching interventions in the national economy ever undertaken—were launched by the laissez-faire Texas conservative, not the community organizer from Chicago. And though few Americans seem to have noticed, those programs worked out pretty well in the end—and both presidents can rightfully claim a share of the credit.

Obama also has kept No Child Left Behind, Bush’s signature education reform, maintained the costly Medicare prescription-drug program, and expanded the higher fuel-economy standards and renewable-energy incentives that Bush passed in his second term. “While Obama ran against Bush’s tax cuts, he ended up preserving roughly 85 percent of them, reversing them for just the top 1 percent of American taxpayers,” Baker writes. “And Obama made one of his highest second-term priorities an overhaul of the immigration system, moving to complete Bush’s unfinished mission.” All correct.

In short, it’s too easy to diss George W. Bush. For many of his detractors, he’s still a walking caricature: Dubya, the Shrub, the lock-jawed dope of Will Ferrell’s road show. But Baker convincingly argues that there’s no understanding where we are today unless we take a cold-eyed look at the reign of Bush and Cheney.

YES, LET’S not forget Cheney, so loathed on the left. Baker shrewdly opted to structure this book as a dual biography, the story of an unprecedented partnership between the president and his deputy. Previous accounts, Baker believes, have tended to miss the full complexity of the two men’s relationship. “Popular mythology had Cheney using the dark side of the force to manipulate a weak-minded president into doing his bidding,” Baker writes. “The image took on such power that books were written about ‘the co-presidency’ and ‘the hijacking of the American presidency.’” But Baker says this is nonsense: the “cartoonish caricature . . . overstated the reality and missed the fundamental path of the relationship.”

No doubt Cheney made himself into the “most influential vice president in American history”—a position he achieved through his unparalleled knowledge of the inner workings of Washington, which he gleaned through decades of service in both the executive branch and Congress. Yet Baker goes on to show how Cheney blew it. Ultimately he squandered this influence as his president moved to the center in his second term. While the basic arc of Bush’s life is by now familiar to most politically interested Americans (his early business failures, his reinvention as a baseball team owner, his fight against alcoholism and his redemption through revivalist Christianity), Cheney’s biography is still obscured by myth, partisan resentment and his own sere public persona. I, for one, was shocked to realize that Cheney is actually just a mere five years older than his president: I’d assumed (like many Americans, I suspect) that he was at least fifteen or twenty years Bush’s senior. Maybe it was just his glabrous head, but Cheney always exuded, and continues to exude, a surly gravitas that the peevish Bush never mastered.

Nowadays we tend to think of Cheney as a kind of cranky old battle robot. But there was a time when he was more of an enfant terrible, a remarkable political prodigy. In 1976, thanks to a wily political patron named Donald Rumsfeld, Cheney became, at age thirty-four, the youngest White House chief of staff in history (under President Gerald Ford). Bossing around underlings came naturally to him. In 1980, as a fledgling congressman, he ran for and won the number-four House post in the Republican Party. At the end of the decade he assumed the job of secretary of defense under President George H. W. Bush, in which capacity he was part of the team that planned and implemented the successful 1991 Gulf War, including the fateful decision to leave Saddam in power once allied forces had expelled him from Kuwait—a decision that Cheney stoutly defended, alleging that it would have been foolhardy to go all the way to Baghdad. Later he changed his mind. It was a career that gave Cheney unparalleled insight into the technology of inside-the-Beltway power.

Nowadays we tend to think of Cheney as a kind of cranky old battle robot. But there was a time when he was more of an enfant terrible, a remarkable political prodigy. In 1976, thanks to a wily political patron named Donald Rumsfeld, Cheney became, at age thirty-four, the youngest White House chief of staff in history (under President Gerald Ford). Bossing around underlings came naturally to him. In 1980, as a fledgling congressman, he ran for and won the number-four House post in the Republican Party. At the end of the decade he assumed the job of secretary of defense under President George H. W. Bush, in which capacity he was part of the team that planned and implemented the successful 1991 Gulf War, including the fateful decision to leave Saddam in power once allied forces had expelled him from Kuwait—a decision that Cheney stoutly defended, alleging that it would have been foolhardy to go all the way to Baghdad. Later he changed his mind. It was a career that gave Cheney unparalleled insight into the technology of inside-the-Beltway power.

But there was something else at work as well. Cheney’s experience in the 1970s, when the post-Watergate Congress was feverishly working to curtail presidential prerogatives wherever it could, left him with a markedly expansive view of executive power. In Cheney’s opinion (one he shared with Rumsfeld), the job of the president and his staff was to push back aggressively against any efforts to impinge upon presidential authority.

It was Cheney, indeed, who realized that the oft-derided office of the vice presidency was an ideal platform for anyone determined to mount an all-out defense of White House supremacy. The story of how Cheney ran Bush Jr.’s vice presidential selection committee, only to end up getting the job himself, has been often repeated. Baker’s version is cautious and nuanced, but still illuminating. “The official version is that Bush never gave up on the idea of having Cheney as his running mate and wore him down,” Baker writes. There is some evidence for this scenario—Cheney, for example, refused the job the first time Bush offered it to him. Yet Baker concedes that it’s hard to entirely dismiss the notion that Cheney, the maestro of plausible deniability, had skewed the whole process in his favor, a verdict that Barton Gellman’s impressive book Angler, which details the efforts of Cheney and his aide David Addington to obtain compromising material about other potential candidates during the vetting process, suggests. Baker observes:

Yet some losing candidates and even some Cheney friends were convinced it was all an elaborate orchestration. “Cheney engineered the whole vice president thing,” said one friend. “The brilliance of Cheney is he let the other alternatives just light themselves on fire, one after the other. It was perfect.” Cheney never said as much to this friend, but it says something that someone close to him would come to this conclusion.

If you’re a student of the science of power, you’ll relish the passages that describe Cheney’s maneuverings. From the very beginning of his vice presidency we see Cheney deftly recalibrating the bureaucratic machinery to his own ends (for example, by melding his high-powered staff with the president’s to an extent that no one else had ever dared to do before him).

One of the most intriguing accounts in the book involves Cheney’s effort, early in 2001, to gut U.S. approval of the Kyoto Protocol, which had been signed by Clinton. Cheney urged Bush to sign a letter that robustly denounced the Kyoto Protocol and rejected the notion of carbon caps (despite a campaign promise favoring carbon caps that actually enjoyed the support of some influential members of his team), then staged an extraordinary end run around the rest of the White House staff.

Cheney personally carried the letter to the Republican leadership in the Senate. Neither Christine Todd Whitman, Bush’s administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, nor Secretary of State Colin Powell, nor National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice was informed ahead of time. Baker persuasively contends that this moment, months before 9/11, marked the real start of the Bush administration’s fateful penchant for unilateralism. The Kyoto letter “made only passing mention of working with other countries to find alternatives to the flawed pact, and no one had prepared the allies for what was coming, feeding the impression of a go-it-alone attitude on the part of the new president.”

The Kyoto episode is a great example of how that go-it-alone philosophy toward other countries mirrored a similar mind-set toward certain checks and balances within the government itself. The vice president’s determined refusal to provide details of his meetings with industry representatives during his deliberations on energy policy, for example, was grounded in the same philosophy of executive dominance. Watergate always loomed large for the old boy; he was determined to engage in his personal rollback campaign, bolstering the presidency by shedding congressional restraints imposed during the Ford administration. Cheney had an opening that was denied his predecessors, too. For obvious reasons, American wars have always tended to empower presidents, and the period following the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington merely affirmed this pattern.

BAKER’S ACCOUNT of 9/11 and its aftermath makes for a gripping read and goes a long way toward illuminating the motives of White House policy makers who had to confront the possibility that the attacks were merely a prelude to an even more apocalyptic assault on the United States:

But Bush saw one of the towers fall and thought to himself that no American president had ever seen so many of his people die all at once before. Three thousand had been killed in the deadliest sneak attack in American history, all on his watch. At the time, he thought it was even more.

He reminds us that Bush, whose presidency was floundering, initially had a rocky time responding to the crisis, but then rebounded to remarkable effect starting with his impromptu remarks at the still-smoking ruins at ground zero in New York. For a while, buoyed by a remarkable bipartisan urge to unity and revenge, his popularity ratings soared to the 90 percent mark.

As it happened, Cheney, as James Mann vividly reported in The Vulcans, was an alumnus of many continuity-of-government exercises during the Cold War era, and his concurrent sensitivity to threats tended to feed the general sense of vulnerability and paranoia. (It was the vice president, for example, who urged Bush to keep away from Washington for most of the day on 9/11 itself; though that may have been a smart move on security grounds, it ultimately exposed the president to criticism.) Baker does an excellent job of summoning up the febrile atmosphere of the fall of 2001, when proliferating false reports and a general state of jumpiness merged with the mysterious anthrax-by-mail attacks and accounts of Osama bin Laden’s meeting with renegade Pakistani nuclear scientists to keep a nation’s nerves on end. And then, in October, a biological-weapons sensor went off in the White House:

“Mr. President,” Cheney started soberly, “the White House biological detectors have registered the presence of botulinum toxin and there is no reliable antidote. Those of us who have been exposed to it could die.” Bush, taken aback, sought to understand what he had just heard. “What was that, Dick?” he asked. Colin Powell jumped in. “What is the exposure time?” he asked. Bush and Condoleezza Rice assumed he was calculating his last time in the White House, trying to figure out whether he had been exposed too. It turned out he had been there within the possible exposure window.

Needless to say, it turned out to be a false alarm. But it’s a vivid example of the not entirely unjustified fears that vexed decision makers at the time.

In contrast to the portraits painted by his enemies, though, the vice president’s actual power over Bush was limited. Cheney was an enabler, someone who smoothed the way, not a man who gave orders to his superior. Baker notes that there is no evidence that Cheney ever succeeded in persuading Bush to adopt positions that he wasn’t already inclined to accept; there are, however, quite a few cases where Bush defied him. Despite Cheney’s urgings, Bush refused to stage the invasion of Iraq in the spring of 2002. And Cheney also strongly opposed Bush’s effort to obtain UN authorization for the war when it finally took place a year later. (The U.S. draft resolution was withdrawn when it became clear that other members of the UN Security Council were prepared to veto it.)

As Baker tells the story, Cheney’s enormous influence over the president was not a figment of the conspiracy theorists’ imagination—but nor did it prove as permanent as they might have supposed. In Bush’s second term in office, eager to craft a positive legacy that would outlive the shame of the Iraq fiasco, the president shifted to the center, leaving Cheney’s neoconservative camarilla suddenly isolated. For years, the neocons had held sway, isolating the State Department in their machinations to enmesh Washington in a war of liberation in Iraq. They succeeded all too well. The disasters that ensued ended up creating shock, if not awe, in Bush’s mind. After the thumping of the 2006 midterm elections, Bush started to shift course. The neocons were out; the realists were in. At the Department of Defense, Rumsfeld eventually gave way to Robert Gates, a major moderating influence on foreign policy. (The shift also deprived Cheney of a crucial ally in interagency squabbles.) Condoleezza Rice assumed Powell’s old job as secretary of state, where she lobbied for a whole range of more moderate foreign-policy positions on fronts ranging from Iran to North Korea. Baker notes that her own bond with the president arguably contained a great deal more of genuine friendship and intimacy—fueled, at times, by a shared love of sports and exercise—than Bush’s relationship with Cheney. (At one point, as Baker recalls, Rice once inadvertently referred to her boss as “my husband” in the presence of journalists.) “By the latter half of his presidency,” Baker writes, Bush “had grown more confident in his own judgments and less dependent on his vice president.”

In one of the book’s most vivid scenes, Bush’s national-security aides convene to discuss the proper course of action against an illicit Syrian nuclear reactor being built with North Korean assistance. Should the United States assist an Israeli strike against the facility? Or simply let the Israelis go it alone? Cheney is the only one at the table to argue, forcefully, for a U.S. raid on the reactor. Bush asks for a show of hands: “Does anyone here agree with the vice president?” No one, as it turned out.

Just in case there’s any doubt about the extent of Cheney’s political isolation by the end of Bush’s second term, Baker frames his book with an account of Cheney’s abortive efforts to persuade Bush to grant a presidential pardon to I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, the Cheney aide convicted by a jury of perjury during a federal investigation to determine the culprit responsible for outing Valerie Plame as a CIA agent (apparently in retribution for an op-ed written by her ex-ambassador husband Joseph Wilson that undercut the administration’s case for war in Iraq). While Bush was willing to commute Libby’s sentence, he refused to overturn the verdict of the jury, opening a breach between him and his vice president that undermines the customary description of Cheney as a Darth Vader figure, capable of shifting an indecisive president through minor exertions of the Force. As Baker shows us in the book on many occasions, Bush was far from pliant.

BAKER HAS done a tremendous job of knitting together the disparate strains of a complex and multilayered narrative. For all its density, the book proceeds at a beach-read velocity that makes it a pleasure to peruse. Especially enjoyable is Baker’s commendable urge to puncture many of the easy myths that still surround the Bush years. (Baker rightly points out that Bush administration hard-liners were not the only ones who genuinely believed that Saddam still had a WMD arsenal, though he also shows how the White House’s determination to prove its case ended up distorting the intelligence and, thus, the case that it made to the world.) Anyone who reads it will come away from this account with their understanding of the period greatly increased—which, after all, is just what a history like this is supposed to accomplish.

It hardly comes as a surprise that a book of such vast scope should leave its share of loose ends. Despite his detailed treatment of the causes of the Iraq War, Baker is a bit too offhanded about its ultimate consequences. He dutifully mentions the number of U.S. and Iraqi dead and essentially leaves it at that. But that really isn’t enough. He doesn’t touch upon how the invasion and its aftermath devastated Iraqi society, vastly strengthening Iran’s position in the region and creating a whole new generation of battle-hardened jihadis who will bedevil the United States for years to come. (Many of them are currently fighting in Syria.) Nor does he dwell on the lingering damage to the U.S. military, the many thousands of U.S. service members left disabled or the immense cost to the American economy. As far as the latter is concerned, some recent estimates put the total at some three trillion dollars—money that might have come in handy during the recent (and continuing) economic unpleasantness. Nor, indeed, does Baker spend quite as much time as he might have on the economic policies of Bush and Cheney and the measures they took that increased the nation’s vulnerability to the shocks that led to the Great Recession. If he can manage to flesh out some of these darker aspects of the Bush-Cheney legacy in later editions, Baker might well claim to have written the definitive account of the period. Even in its current form, though, his book is a remarkable achievement.

Christian Caryl is a senior fellow at the Legatum Institute in London and a contributing editor at The National Interest and Foreign Policy.

Pullquote: There is no evidence that Cheney ever succeeded in persuading Bush to adopt positions that he wasn't already inclined to accept; there are, however, quite a few cases where Bush defied him.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review