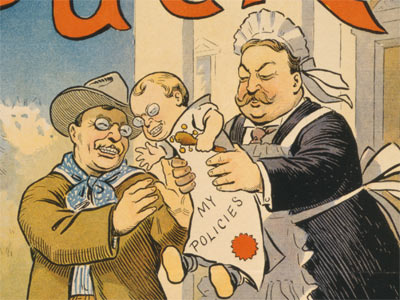

Teddy Roosevelt and Taft: The Odd Couple

Mini Teaser: Few American stories of personal fellowship are as poignant as the Roosevelt-Taft friendship—and its brutal disintegration.

Doris Kearns Goodwin, The Bully Pulpit: Theodore Roosevelt, William Howard Taft, and the Golden Age of Journalism (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2013), 928 pp., $40.00.

IN THE EARLY 1890s, when Theodore Roosevelt met William Howard Taft during their early stints as government officials in Washington, Roosevelt said, “One loves him at first sight.” Later, as president, Roosevelt extolled the virtues of Taft, then U.S. governor-general of the Philippines: “There is not in this Nation a higher or finer type of public servant than Governor Taft.” After Taft became Roosevelt’s war secretary, the president reported to a friend that the new cabinet chief was “doing excellently, as I knew he would, and is the greatest comfort to me.” Before going on vacation, TR assured the nation that all would be well in Washington because “I have left Taft sitting on the lid.” Subsequently, when Taft expressed embarrassment about a news article unflattering to Roosevelt that had been spawned by a Taft campaign functionary, the president was unmoved. “Good heavens, you beloved individual,” he wrote, suggesting Taft should get used to false characterizations in the press, as he himself had done, although “unlike you I have frequently been myself responsible.”

Such expressions betokened a special relationship between public servants that extended beyond political expediency and touched deep cords of personal affection. For his part, Taft described their friendship as “one of close and sweet intimacy.”

After Taft succeeded Roosevelt as president and sought in his own way to extend the TR legacy, though, the friendship fell apart. Roosevelt, concluding his old chum didn’t measure up, turned on him with a polemical vengeance that negated the mutual affections of old. Going after his former friend, first in an effort to wrest from him the 1912 Republican presidential nomination and then as an independent general-election candidate, Roosevelt destroyed the Taft presidency—and brought down the Republican Party in that year’s canvas. When the Taft forces prevailed in a typical credentials fight at the GOP convention, TR seized upon it as proof of Taft’s mendacity and corruption. “The receiver of stolen goods is no better than the thief,” he declared. When Taft’s political standing began to wane, largely from TR’s own attacks, he dismissed his erstwhile companion as “a dead cock in the pit.” The former president said, “I care nothing for Taft’s personal attitude toward me.”

In the annals of American history, few stories of personal fellowship are as poignant and affecting as the story of the Roosevelt-Taft friendship and its brutal disintegration. But it carries historical significance beyond the shifting personal sentiments of two politicians. This particular story of personalities takes place against the backdrop of the Republican Party’s emotion-laden effort—and the nation’s effort, and these two politicians’ efforts—to grapple with the progressive movement and the pressing contradictions and societal distortions created by industrialization.

Now the distinguished historian Doris Kearns Goodwin scrutinizes the Roosevelt-Taft saga, bringing to it her penchant for presenting history through the prism of personal storytelling. In No Ordinary Time, she illuminated the Franklin Roosevelt presidency by probing the complex and mysterious marriage of Franklin and Eleanor. In Team of Rivals, which examined Abraham Lincoln’s unusual decision to fill his cabinet with his political competitors, she not only laid bare crucial elements of Lincoln’s political temperament but also presented a panoramic survey of his time—and gave currency to a term that now figures prominently in the nation’s political lexicon. And now, with The Bully Pulpit, she deciphers a pivotal time in American politics through the moving tale of TR and Will, girded by her characteristic deft narrative talents and exhaustive research. And there’s a bonus: she weaves into her narrative the story of S. S. McClure’s famous progressive magazine, named after himself and dedicated to the highest standards of expository reporting and lucid writing.

Goodwin’s narrative takes on a particularly powerful drive as the TR-Taft friendship crumbles—and then, after the sands of time have eroded the sharp edges of animus, is restored. The author’s narrative doesn’t bring a strong focus to Roosevelt’s powerful views and actions on foreign policy—his vision of America as preeminent global power, for example, or his dramatic decision to send his Great White Fleet around the world as a display of U.S. naval prowess and a spur to congressional support for his cherished naval buildup. Nor does she trace in elaborate detail the challenging developments in the Philippines, called by TR biographer Kathleen Dalton “the war that would not go away” (although TR finally brought it to a conclusion through a notable level of military brutality directed against insurgent forces). Rather, this is a book about the emergence of the progressive impulse, which sought to apply federal intervention to thwart “the corrupt consolidation of wealth and power” within industrial America. Goodwin clearly believes this counterforce was necessary to protect ordinary Americans from the unchecked machinations of the “selfish rich,” industrial titans, and corrupt local and state governments.

She is correct, of course. The advent of American industrialization had generated substantial economic growth through the latter half of the nineteenth century, and that in turn had fostered the creation of vast new wealth. The Republican Party, as the champion of this development, enjoyed a dominant position in American politics. But the party was beginning to falter at century’s end as it failed to address the attendant problems of the industrial era—predatory monopolies, abuse of the working classes, fraud and malpractice in the distribution of food and medicines. A new turn was necessary, but any suggestion of one antagonized entrenched interests, many within the Republican Party itself. These included industrial plutocrats, their cronies among the urban political bosses and allied members of Congress. A potent political clash was probably inevitable.

ROOSEVELT AND TAFT, born thirteen months apart in the late 1850s, enjoyed comfort and privilege as children. Taft’s father was a prominent Cincinnati lawyer and judge who served as U.S. war secretary and attorney general in the administration of President Ulysses Grant. He was a loving but demanding father who approached life as relentless duty, devoid of anything resembling joy. By contrast, Roosevelt’s father, scion of a family that had amassed a substantial fortune in New York commerce, real estate and banking, took delight in his work but skillfully combined it with a robust social life and exuberant family activities. He was “the most intimate friend of each of his children,” recalled Theodore’s sister, Corinne.

ROOSEVELT AND TAFT, born thirteen months apart in the late 1850s, enjoyed comfort and privilege as children. Taft’s father was a prominent Cincinnati lawyer and judge who served as U.S. war secretary and attorney general in the administration of President Ulysses Grant. He was a loving but demanding father who approached life as relentless duty, devoid of anything resembling joy. By contrast, Roosevelt’s father, scion of a family that had amassed a substantial fortune in New York commerce, real estate and banking, took delight in his work but skillfully combined it with a robust social life and exuberant family activities. He was “the most intimate friend of each of his children,” recalled Theodore’s sister, Corinne.

Both youngsters demonstrated acute intellectual abilities and developed early ambitions to leave a mark on society. Both emerged among their peers as natural leaders to whom others looked for guidance. Both gravitated to the law and to public service and never hankered for private attainment or wealth. Both experienced significant career propulsion at an early age. Both embraced a reformist sensibility dedicated to clean government and opposition to political bossism. Both began their formative years of political consciousness with a mild conservatism of the kind typically found among the privileged, but both later developed an appreciation for elements of the progressive ethos.

There the similarities end. Roosevelt was a man in perpetual motion—restless, forceful, cocky, a “bubbling, explosively exuberant American,” as the Boston Daily Globe put it. A British viscount said he had seen “two tremendous works of nature in America—the Niagara Falls and Mr. Roosevelt.” The writer William Allen White suggested TR’s mind moved “by flashes or whims or sudden impulses.”

Roosevelt’s theatrical self-importance led even his children to acknowledge that he wanted to be “the bride at every wedding and the corpse at every funeral.” His speech sparkled with vivid expressions that reflected his unabashedly held strong opinions. When Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes came down on what TR considered the wrong side of an important decision, Roosevelt declared, “I could carve out of a banana a judge with more backbone than that.”

On the other hand, wrote White, Taft’s mind moved “in straight lines and by long, logical habit.” He was easygoing—modest in demeanor, conciliatory by temperament. While Roosevelt garnered attention by putting himself forward with endless quips, asides and pronunciamentos, the more self-conscious Taft let others come to him, and because he stood out as solid and fair-minded they almost always did. White described him as “America incarnate—sham-hating, hardworking, crackling with jokes upon himself, lacking in pomp but never in dignity . . . a great, boyish, wholesome, dauntless, shrewd, sincere, kindly gentleman.”

As the two men made their way in government service, Roosevelt moved amid a constant cloud of controversy. And yet he discovered that his penchant for relentlessly pushing his pet issues to the forefront and forcing decisions could be highly effective. As the youngest member of the New York state legislature, he became one of New York’s leading reform politicians. “I rose like a rocket,” he later explained with characteristic pride.

Taft meanwhile gravitated to the judiciary, which proved compatible with his judicious nature. At the remarkably young age of twenty-nine, he was appointed an Ohio state judge. He distinguished himself sufficiently to win a presidential appointment as U.S. solicitor general in the Benjamin Harrison administration. Thus, he moved with his wife Nellie to Washington and took up residence near Dupont Circle, just a thousand feet from the new residence of Theodore Roosevelt, recently appointed to the Civil Service Commission. The two took to walking together to work each morning.

Based on their experiences under Harrison, Taft would have appeared to be on the faster track. The president found his temperament much more to his liking than that of Roosevelt—who, the president complained, seemed to feel “that everything ought to be done before sundown.” Sensing the president’s disdain, Roosevelt complained to his sister that his fight against corruption in federal employment practices was conducted with “the little gray man in the White House looking on with cold and hesitating disapproval.” Goodwin writes that Harrison considered firing the underling but feared a backlash from the large numbers of people who appreciated his forceful anticorruption agitations. Conversely, Harrison took an immediate liking to Taft, inviting him to call at the White House “every evening if convenient.” Harrison eventually nominated the thirty-four-year-old Taft to a seat on the U.S. Circuit Court, the second highest in the federal judicial system. Roosevelt, meanwhile, returned to New York City as police commissioner.

THE NEXT Republican president, William McKinley, developed similar views of the two men. When he needed a judicious and calm figure to become governor-general of the Philippines, he chose Taft. But when Roosevelt’s friends sought to get him appointed assistant naval secretary, McKinley hesitated. He told one Roosevelt promoter, “I want peace, and. . . . I am afraid he is too pugnacious.” But eventually he relented and gave Roosevelt the job, to which the new assistant secretary brought a whirlwind of activity aimed at getting the navy ready for a war with Spain that he not only foresaw but also welcomed with a kind of romantic martial spirit.

When war came, Roosevelt embraced it not only philosophically but also physically, organizing his “Rough Rider” militia unit that distinguished itself in the campaign to capture the crucial city of Santiago in Cuba. Leading his famous charge up Kettle Hill on the San Juan Heights, he demonstrated a disregard for his personal safety that was courageous and foolhardy in equal measure. That single action cemented his place among his countrymen as the most stirring personality of his time. He already had become nationally known for his impetuous ways and reformist zeal; now he was a national hero.

Roosevelt promptly parlayed his new status into a successful run for New York governor. His budding progressivism ran headlong into the conservative doggedness of the state’s political bosses, particularly Senator Thomas Platt, who ran the New York Republican machine. Although Roosevelt sought to nurture a working association with Platt, he ran afoul of the senator when he pushed for a business franchise tax on corporations—streetcar firms, telephone networks, telegraph lines—that had been given lucrative business opportunities through state franchises. “You will make the mistake of your life if you allow that bill to become a law,” Platt warned, hinting at a suspicion that Roosevelt harbored Communist or socialist tendencies. Roosevelt countered: “I do not believe that it is wise or safe for us as a party to take refuge in mere negation and to say that there are no evils to be corrected.” He got the bill passed, though with some amendments designed to placate Platt if possible. The party boss sought to put a friendly face on the outcome, but the machine now considered Governor Roosevelt a marked man.

Undeterred, Roosevelt sent to the legislature a call for state actions to curtail the growth and power of corporate trusts, the increasingly monopolistic enterprises that sought to squeeze out competitors, often through corruption and dishonesty, and thus gain dominance over crucial burgeoning markets. Taking a cue from his friend Elihu Root, one of the country’s leading lawyers and war secretary in the McKinley administration, Roosevelt carefully crafted his language on the trusts to avoid any hint of radicalism. He stressed, “We do not wish to discourage enterprise; we do not desire to destroy corporations; we do desire to put them fully at the service of the State and the people.” Notwithstanding this measured approach, which was to become a hallmark in subsequent years, the antitrust effort never got off the ground. The reason, he concluded, was that the problem had not seeped sufficiently into the political consciousness of the people.

But Roosevelt’s apostasy was never forgotten by Boss Platt and his cronies. They sought to oust him from the governor’s chair and perhaps even deny him renomination at the next GOP convention. The solution came in the form of a movement to get Roosevelt on the McKinley ticket as vice president in the 1900 balloting. Roosevelt wasn’t sure he could handle being stuck in such a passive, backwater job, but the threat of being upended as governor proved a powerful incentive. As his friend Henry Cabot Lodge succinctly put it, “If you decline the nomination, you had better take a razor and cut your throat.”

Less than seven months after assuming the vice presidency, TR became president, to the consternation of his foes, following the assassination of McKinley in September 1901. The country’s new chief executive was just forty-two years old.

“I am President,” he declared with characteristic audacity, “and shall act in every word and deed precisely as if I and not McKinley had been the candidate for whom the electors cast the vote for President.” Roosevelt proved adept in working with the congressional opposition and in encasing his antitrust goals in descriptive language designed to be moderate, measured and balanced. Federal power over the trusts, he declared, must be “exercised with moderation and self-restraint.” And he argued that Democratic calls to eradicate all trusts would “destroy all our prosperity.” But he encountered an apathetic public on the issue, just as he had during his days as New York governor.

ENTER S.S. MCCLURE. He hit upon the idea of sending his talented young writer, Ida Tarbell, after a single trust, thus rendering the story vivid and understandable. She chose John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, “the Mother of Trusts.” In a twelve-part series that later became a best-selling book, Tarbell documented, among other things, how Rockefeller induced corrupt railroad magnates to impose discriminatory freight rates upon his independent rivals, thus killing off competition and cornering the mushrooming oil market. The reaction was electric. Suddenly the trust problem became a matter of high concern to the nation.

This helped pave the way for Roosevelt’s progressive agenda, which he pressed with his usual urgency. He pushed through a reluctant legislature the Hepburn Act, which authorized the Interstate Commerce Commission to set the rates charged by railroads to their shipping customers—a direct reply to Tarbell’s famous Rockefeller series. He got Congress to create the Department of Commerce and Labor (later split into two separate departments), with regulatory powers over large corporations, and to pass legislation expediting prosecutions under the Sherman Antitrust Act. Responding to other “muckraking” journalism in McClure’s Magazine and elsewhere, he fostered passage of the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act. Roosevelt’s Justice Department filed suit against the Northern Securities Company under antitrust laws and brought the company down. It broke up Standard Oil and went after the beef trusts that had colluded to parcel out territories and fix prices, resulting in sharp cost increases for consumers of meat.

In addition, he personally—and adroitly—handled a coal-strike crisis that threatened the national economy. And he preserved some 230 million acres in public trust through creation of a multitude of national parks, forests and monuments. In foreign affairs, he set in motion the building of the Panama Canal by fomenting a successful Panamanian revolt against Colombia and then negotiating with the new Panamanian nation for rights to the swath of isthmus needed for the canal. He put himself forward as mediator to foster a negotiated end to the Russo-Japanese War, a bit of diplomacy that earned him a Nobel Peace Prize.

Roosevelt deployed federal power on behalf of national goals, far beyond anything seen since the Civil War. But two realities surrounding the Roosevelt presidency merit attention. First, the Rough Rider president, in bringing progressive precepts into the national government, stopped short of the kinds of redistributive economic policies favored by more radical progressives of the era. His aim was to level the playing field by outlawing practices and privileges that allowed favored groups to thrive at the expense of the mass of ordinary citizens. He didn’t embrace the goal of a graduated income tax, for example. And, although he despised the high tariff rates of the McKinley administration, he shied away from attacking those discriminatory levies because he wasn’t prepared to expend the kind of political capital that would have been required for such a fight against party bosses committed to protectionist policies.

Indeed, Roosevelt constantly expressed his preference for middle-ground approaches that raised the ire of both laissez-faire conservatives and more radical elements of the progressive movement. Even as New York governor, he confessed that he wasn’t sure which he regarded “with the most unaffected dread—the machine politician or the fool reformer.” He added that he was “emphatically not one of the ‘fool reformers.’” As president he declared that “there is no worse enemy of the wage-worker than the man who condones mob violence in any shape or who preaches class hatred.” He identified “the rock of class hatred” as “the greatest and most dangerous rock in the course of any republic.”

Second, Roosevelt found that during the latter part of his seven-year presidency he no longer possessed the political clout to get his initiatives through Congress. He attributed this to the “lame duck” effect of his promise to the American people, when he ran for a second term, that he wouldn’t seek a third. Goodwin credits this rationale, and no doubt it contributed to his diminished political force as his White House tenure wound down. But another factor was that the country had absorbed about as much progressivism as it was prepared to handle at that time in its history, absent the kind of crisis that emerged a generation later with the Great Depression. Indeed, even Roosevelt’s distant cousin, Franklin Roosevelt, found his New Deal initiatives reaching their limit after he sought to exploit his landslide reelection victory of 1936 by “packing” the Supreme Court.

But Theodore Roosevelt, with his big domestic initiatives, had altered the political landscape of America and thus had emerged as a leader of destiny among American presidents. Accepting, based on his two-term commitment, that he must relinquish the presidency, he deftly fostered the election of Taft as his successor and then headed off to Africa for a year of big-game hunting, confident that his friend would carry on his policies. Upon his return, he thought otherwise.

THROUGHOUT THEIR friendship and intertwined careers, Roosevelt and Taft had been a powerful combination, complementing each other’s weaknesses and foibles. That was in part what each appreciated about the other. Roosevelt the impetuous, instinct-driven politician appreciated Taft’s measured, careful decision making. Taft admired Roosevelt’s ability to size up a political situation instantly and seize the initiative on it. Roosevelt wrote: “He has nothing to overcome when he meets people. I realize that I have always got to overcome a little something before I get to the heart of people. . . . I almost envy a man possessing a personality like Taft’s.” For his part, Taft often wished he could incorporate some of Roosevelt’s quick insightfulness and scintillating use of the language. “I wish I could make a good speech,” he confessed to his wife, adding that a recent performance in Michigan had left “a bad taste in my mouth.”

But once their paths diverged with Roosevelt’s trip to Africa, these differences in temperament took on an entirely new coloration. Progressives who expected Taft to carry on Roosevelt’s policies often seemed unmindful that even Roosevelt had failed to carry on his own policy preferences to the end of his presidency. Worse, the most ardent progressives seemed to want Taft to operate in TR fashion. That wasn’t possible. At one point, when President Taft shied away from taking a particular fight to the American people, as TR no doubt would have done, he said wistfully, “There is no use trying to be William Howard Taft with Roosevelt’s ways.”

Indeed, there was a halting quality to Taft’s leadership. But he pursued significant elements of the progressive agenda, ultimately with considerable success. While Roosevelt had avoided a tariff fight lest he drive a wedge through his party, Taft plunged into the fray and helped produce trade legislation that represented a significant party turnaround on the issue. Though he didn’t get as much as he wanted and radical reformers complained when he didn’t veto it, the legislation represented a significant political achievement. But then the president unwisely heralded the bill as “the best bill that the Republican party ever passed,” signaling that he had no intention of pursuing any future tariff reductions. Predictably, the radical reformers cried betrayal.

Despite such political lapses, Taft brought forth a new railroad bill that bolstered the power of the Interstate Commerce Commission to initiate action against rate hikes. He created a “special Commerce Court” to expedite judgments and brought telegraph and telephone companies under the authority of the Interstate Commerce Act. New reporting requirements for campaign contributions were enacted. Arizona and New Mexico joined the union as states. A new Bureau of Mines emerged to regulate worker safety in the mining industry. Taft also fostered the creation of a postal savings bank to provide people of limited means a safe haven for their savings. Much of this was possible because of Taft’s deft deal making during the arduous efforts to get his tariff bill through Congress, when he accepted amendments from old-guard conservatives in exchange for later support for his broader agenda.

In addition, Taft proposed legislation to enact a corporate income tax, which cleared Congress, and a constitutional amendment authorizing an individual income tax, which also cleared Congress and was sent to the states for ratification. (It was ratified in 1913.)

It’s impossible to know what drove Roosevelt to ignore all these achievements and go after his old friend, to destroy his presidency and deliver a powerful blow to his own party. But it’s difficult to escape the conclusion that the greatest factor was the former president’s outsized ego. A telling clue may be the report, mentioned by Goodwin, that Roosevelt told a friend he would cut his hand off at the wrist if he could retrieve his pledge not to run for a third term. Wisconsin senator Robert La Follette, a close Roosevelt observer, speculated that he left the White House with a prospective 1916 run for president firmly in mind. But, when he saw Taft’s weakness with GOP reform elements and tasted the nectar of his own lingering popularity, he “began to think of 1912 for himself. It was four years better than 1916.”

After all, it isn’t easy becoming an ex-president at age fifty, yielding to others the power and glory that once were so heady and thrilling in one’s own hands. For a man who wanted to be the bride at every wedding and the corpse at every funeral, it was particularly difficult to accept such a loss of position and power. In any event, while Roosevelt couldn’t win on an independent-party ticket, he could keep Taft from winning. And that paved the way for the presidency of Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

GOODWIN BELIEVES Taft’s political demise stemmed from his own limitations as president. “For all of [his] admirable qualities and intentions to codify and expand upon Roosevelt’s progressive legacy,” she writes, “he ultimately failed as a public leader, a failure that underscores the pivotal importance of the bully pulpit in presidential leadership.” Perhaps. But presidential leadership comes in many guises, and ultimately it’s about performance. Taft’s performance, based on the political sensibility he shared with Roosevelt, was exemplary. His largest burden was the split within the Republican Party spawned by Roosevelt’s own resolve to interject progressive concepts into national governance. This resolve, coupled with Roosevelt’s own increasingly rough-hewn manner of dealing with Congress, had absorbed his last stores of political capital long before the end of his presidency.

But Taft managed to wend his way through this political environment and keep the flame alive, to replenish the stores of political capital through his own deft deal making and good-natured compromising. His most dangerous adversaries turned out to be those people Roosevelt had called “fool reformers.” Then his old friend Teddy returned from Africa and joined the fool reformers. But suppose Roosevelt had taken a different tack. Suppose he had rushed to the defense of his old companion and heralded his middle-ground techniques as being firmly in the tradition of his own political ethos. Suppose that, in doing this, he had enabled Taft to arrive at a synthesis of politics that could have sustained a winning coalition and carried him through the coming election and into a second term. Then Roosevelt’s legacy would have remained secure under the Republican banner, and he would have been positioned to take ownership of the 1916 canvas, when he would have been a vigorous fifty-eight years old.

Instead, the country saw a party rupture based on atmospherics, brazenly inaccurate accusations, ideological fervor and personal whims writ large. It was the politics of temper tantrum, the product of a man whose most outrageous traits, though frequently charming, had always been potentially problematic but generally under control. Now they erupted onto the political scene with unchecked force, sweeping his old friend, his party and his country into the resulting vortex.

Robert W. Merry is the political editor of The National Interest and an author of books on American history and foreign policy.

Pullquote: The country saw the GOP rupture based on atmospherics, brazenly inaccurate accusations, ideological fervor and personal whims writ large. It was the politics of temper tantrum.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review