America's History of Protectionism

Protectionism has been a frequent feature of the republic since its founding.

IN LATE August 1985, while President Ronald Reagan vacationed at his ranch above Santa Barbara, California, his political director, Ed Rollins, had dinner one Saturday night with reporters for the New York Times and Washington Post. The mischievous politico leaked a story that received front-page treatment Monday morning. President Reagan had decided, the newspapers reported, to reject the pleas of U.S. shoe manufacturers for import tariffs designed to protect them from foreign competition. No big surprise there. Reagan was known as a fervent free trader, hostile to tariffs and other barriers to global commerce.

But discerning Washington hands detected a curious disparity in how the two influential newspapers handled the story. The Post focused on the shoe decision, noting only in passing, that Reagan also was weighing actions to counter unfair practices used by U.S. trade partners. The Post headline read, “Reagan Set to Reject Shoe Curbs.” But the Times turned that around with a top headline that stated, “Reagan Weighing Trade Sanctions, Officials Report.” The paper’s lead paragraph emphasized the president’s decision to weigh “punitive actions” against errant nations abusing America’s free-trade principles.

This led to confusion about Reagan’s true stance on trade at a time when that issue was roiling the country’s politics and when some White House clarity was needed. The president had his press secretary inform White House reporters that Reagan would deliver a major trade address in about a month. A trade-policy struggle within the administration ensued that was so intense that the president’s speechwriters were barred from creating the final draft of the speech.

This episode exemplifies the contention that has surrounded the trade issue throughout American history, starting with Alexander Hamilton, the country’s first treasury secretary and also its first significant protectionist. Today, protectionism is back. The main drivers of this new surge are Republican presidential nominee Donald Trump and the Democratic insurgent Bernie Sanders. Even Hillary Clinton is playing a role. Far from being an aberration, opposition to free trade has been a constituent part of America’s history.

THE ED ROLLINS episode reflected the fact that Reagan faced a political problem of serious magnitude in his second term. Protectionist sentiment was growing in Congress, unleashed by burgeoning imports primarily from Asia. Some three hundred protectionist bills had been introduced in Congress to help various industries beset by foreign competition, including electronics, appliances, textiles, clothing, toys and automobiles. The struggling shoe industry had placed itself at the vanguard of this movement. In fifteen years, U.S. shoe manufacturers had shuttered two-thirds of their domestic factories as shoe imports to the United States grew from just 22 to 76 percent. In 1977, Reagan’s predecessor, Democrat Jimmy Carter, had imposed quotas on shoes imported from Korea and Taiwan, but Reagan had allowed them to lapse.

Now, in the autumn of 1985, some Reagan aides, notably Rollins himself and U.S. Trade Representative Clayton Yeutter, were telling the president that, if he didn’t throw a bone here and there to beleaguered manufacturers, angry protectionists in Congress would gain sufficient strength to challenge the administration’s free-trade stance. Officials at the Commerce, Labor and Agriculture Departments agreed. But Secretary of State George P. Shultz and Treasury Secretary James A. Baker III opposed imposing protectionist measures unilaterally. They favored negotiations with trading partners to end unfair trading practices, using existing sanctions authority as a bargaining chip.

The shoe industry presented a revealing case study. The U.S. International Trade Commission, an independent federal agency, had responded to industry pleas by recommending quotas on shoe imports, restricting them to 60 percent of the American market for five years. But footwear retailers retorted that restrictions would cost consumers billions of dollars in higher shoe prices. One dissenting trade commissioner said the quotas would only save twenty-six thousand U.S. jobs at the cost of $1.28 billion to consumers annually, three times the wages of the workers whose jobs would be saved. Reagan rejected the quota idea. Other administration officials suggested a 30 percent tariff to be phased out over five years—a compromise designed to give the domestic industry relief without imposing actual import restrictions. Reagan rejected this option as well. One official told reporters that he “just didn’t buy the argument that we should accept a small dose of protectionism to head off a larger injection.”

But the administration still needed a coherent policy. Reagan needed to assuage agitated congressional protectionists while still preserving his fundamental free-trade convictions. The presidential speech, slated for Monday, September 23, 1985, was designed to serve this purpose. Just after noon on the Thursday before the scheduled address, White House speechwriter Bentley Elliott completed the final draft. Elliott and his fellow speechwriters saw themselves as the president’s keepers of the conservative flame—free-market believers who followed the dictum so popular among administration hard-liners, “Let Reagan be Reagan.” The draft was a rousing defense of free trade and a pugnacious attack on the nettlesome protectionist forces swirling around Capitol Hill. This, thought Elliott, was what Reagan wanted.

But when the draft reached the office of White House Chief of Staff Donald Regan, he exploded. One of Regan’s top aides called it “an abomination,” and Regan thought the draft took on a politically risky tone that could anger members of Congress and fuel protectionist fires. Regan sent it back for a rewrite, then called Elliott into the Old Executive Office Building to say the task was being yanked away from him. A Regan aide, Alfred Kingon, would write the speech in the West Wing. Out went the rousing free-trade rhetoric; in came rough language directed at what the United States considered unfair practices employed by its trading partners. A top Regan hand dismissed the speech-writing team as “just a bunch of ideologues who are hep on free trade.”

When a Wall Street Journal reporter got his hands on Elliott’s final draft and utilized it to pry out elements of the internal dispute, both sides used the reporter to cast darts at the opposition through quotations in the subsequent story. Thus did a nasty internal controversy become a public spectacle. And all this occurred in an administration that fully favored free trade; the only question was the tactical response to protectionist agitations welling up from within the country. Such was the capacity of the trade issue to wreak political havoc.

PROTECTIONISM HAS been a significant part of the country’s trade history going back to its first revenue law, crafted in 1789 by George Washington’s financial wizard, Hamilton. This original tariff bill imposed an average taxation level of only about 8.5 percent on imported goods. Hamilton argued that any protection encompassed in those duties, as opposed to revenue requirements, should be discontinued as soon as protected industries established themselves in the American economy. But northeastern industrialists predictably asserted that protection should be substantial and permanent to ensure national prosperity.

The trade issue comes into focus through an understanding of the political conflict between Hamilton and Thomas Jefferson at the dawn of the American republic. Hamilton favored executive power wielded by elites for the purpose of economic expansion and national greatness. He advocated federal-level projects and policies—particularly a powerful national bank and protective tariffs to help budding manufacturers and finance federal action—to pull up the nation from above. Hamilton’s views, refined by the next generation of political leaders, became the foundation for Henry Clay’s Whig Party and his philosophy of government, which he called the “American System.” This model emphasized the construction of federal public works such as roads, bridges and canals. High tariffs would also be enacted, in order to pay for civic programs and boost industrial expansion.

By contrast, Jefferson and his later devotee, Andrew Jackson, opposed high levels of governmental intrusiveness into the private economy. Such policies, they argued, would inevitably lead to special privileges for the favored few. They wanted to keep tax levels as low as possible and reduce federal interference so the people could build up the nation from below.

The Hamilton-Clay forces won the first battles. They created a national bank (actually, two banks, both chartered at different times by the federal government) and enacted a major tariff bill during the presidency of John Quincy Adams, whose philosophy was in the Hamilton-Clay mold (Clay was his secretary of state). This bill slapped high duties on iron, molasses, distilled spirits, flax and various finished goods. Northern producers thrived under the protections of the tariff. But southerners hated the bill for two reasons: it raised prices on necessities not produced in the South; and by crimping the importation of British goods, it reduced Britain’s ability to purchase southern cotton. Southerners called Adams’s import tax the “Tariff of Abominations.”

South Carolina decided it would escape this particular abomination through a highly provocative doctrine called “nullification.” The idea was that the state would exercise what it considered its sovereignty in declaring the law null and void. Here we had the country’s first really high tariffs generating severe regional tensions that culminated, during the subsequent Jackson administration, in an ominous constitutional crisis. As a Democrat, Jackson despised high tariffs, but he had declined to expend the political capital required to reduce the Tariff of Abominations. He found himself in the position of having to defend the tariff against what he deemed treasonous threats from a southern state. Jackson quickly made clear he would not tolerate this assault on the Constitution.

“Please give my compliments to my friends in your state,” he told a South Carolina congressman.

And say to them, that if a single drop of blood shall be shed there in opposition to the laws of the United States, I will hang the first man I can lay my hand on engaged in such treasonable conduct, upon the first tree I can reach.

He infused the threat with credibility, and the nullification movement fizzled, though Jackson also helped craft a compromise reduction in tariff rates to somewhat mollify South Carolinians. Still, the tariff issue continued to stir political tensions throughout the country. Whereas before the Adams presidency average tariff payments generally fluctuated between 16 and 26 percent, afterward the levies typically reached 50 percent, then hovered around 35 percent following Jackson’s compromise.

That changed with the emergence of James Polk, a mild-mannered but politically obstinate Jackson protégé who became president in 1845. Polk crafted a doctrine designed to slash tariff rates while minimizing the agitations of northern industrialists. First, he insisted that tariff rates should not exceed levels needed to run the government on an economically sound basis; second, within that range he accepted targeted duties to benefit particular industries needing protection. The Polk Bill (sometimes named for his treasury secretary, Robert Walker) was generally considered a “free-trade” measure. It passed Congress in 1846 and served as the country’s fiscal foundation through the 1850s. Its tariff percentages generally ranged between 20 and 28 percent.

But the protectionist forces never accepted defeat, and in 1859 two prominent house members, Whig Justin Morrill and Republican John Sherman, crafted legislation to raise tariff rates substantially. After clearing the House, it stalled in the Senate—until Southern secession eviscerated the opposition. With the start of the Civil War, even free traders jumped aboard. The New York Evening Post, which had dismissed the Morrill-Sherman measure as “a booby of a bill,” now argued that revenue needs generated by the war demanded cooperation between free traders and protectionists. After the war, said the paper, it would go back to being a free-trade publication.

But after the war, the country was saddled with a huge war debt, and tax cutting wasn’t on the agenda. Even during the war, Congress passed, and President Lincoln signed, ten tariff bills. Lincoln, a Clay Whig from his earliest days in politics, embraced the American System with complete fealty, including the call for high protective tariffs. As early as 1832, he declared, “My politics are short and sweet, like the old woman’s dance. I am in favor of a national bank . . . and a high protective tariff.” After the war, the party of Lincoln became the party of industrial expansion, which brought an added political impetus to the protectionist commitment. Throughout these postwar decades, tariff rates often hovered over 40 percent.

When New York Democrat Grover Cleveland became president in 1885, he promptly sought to reduce tariffs, in keeping with his party’s longtime philosophy. He found an ally in House Ways and Means chairman Roger Q. Mills, a rugged Texan whose free-trade views harked back to James Polk. He thought all raw materials should be duty-free while taxes on manufactured items should be reduced substantially. Under his leadership, the House passed a bill along those lines, but in the Republican-dominated Senate it encountered the granite-like opposition of Rhode Island Sen. Nelson Aldrich, whose devotion to his wool, cotton and sugar constituents would have rendered him a protectionist even if he hadn’t been ideologically committed to that philosophy already. Aldrich and Iowa Sen. William Allison amended the Mills measure substantially, removing many items from Mills’s free list and restoring high tariff rates on numerous imports. The measure cleared the Senate and went back to the House, where it languished in Ways and Means without any prospect of reaching the floor.

Thus, as the country entered the 1888 election year, it had two different tariff bills representing two different fiscal philosophies. Republican Benjamin Harrison defeated Cleveland that November, and protectionism was immediately placed on the agenda.

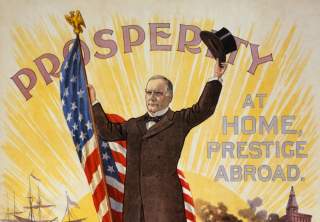

Enter William McKinley of Ohio, the new chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee. McKinley set about crafting the most comprehensive tariff bill the country had ever seen, encompassing some four thousand separate items. So earnest was McKinley in supporting protectionism that the famous progressive writer Ida Tarbell resorted to ridicule in describing him. He had an advantage, she said, “which few of his colleagues enjoyed—that of believing with childlike faith that all he claimed for protection was true.” He even sought to raise tariff rates on some items to preclude any importation of them at all, including woolens, higher-grade cottons, cotton knits, linens, stockings, earthen and china ware, and all iron, steel and metal products. McKinley placed duties for the first time on wheat and other agricultural products to address robust global increases in agricultural production, much of it with cheap labor. “This bill is an American bill,” he said. “It is made for the American people and American interests.”

The crusty Roger Mills, by contrast, rejected the idea that market constrictions could generate prosperity. What Republicans didn’t understand, he argued, was that international trade was like any other human transaction. To get something, you must give something. So it was with the foreigner who wants to sell his products. Mills declared,

Let in his cottons, woolens, wool, ores, coal, pig-iron, fruits, sugar, coffee, tea—let all these things come into the country, because when you do that something has to go out to pay for them. . . . That will create a demand for that American product.

McKinley had the votes to get his bill through the House, and Aldrich shepherded his own version through the Senate. After the “McKinley Tariff” became law in 1890, the political reaction came swiftly and severely. With Americans evenly divided between protectionists and free traders, any bill extending so far in either direction was destined to generate anxiety. Beyond that, after opponents predicted big increases in the price of household goods, clever tradesmen exploited the opportunity to raise prices even before the tariff act could have any real impact. Anxiety turned to anger. In November, Republicans took a beating in the midterm elections, and McKinley lost his congressional seat by three hundred votes. Cleveland won the White House again two years later and promptly sought to reduce tariffs once again. Although the bill that emerged from Congress at his behest did not go as far as he wanted (he let it become law without his signature), it did cut into the magnitude of the McKinley measure.

But the stubborn, plodding Ohioan refused to give up on either his political career or protectionism. He ran for Ohio governor and won, then won reelection two years later. In 1896 he ran for president successfully, largely because Cleveland’s second term was beset by one of the most crushing economic downturns in the nation’s history. Few Americans continued to press for tariff reduction like that of Cleveland’s second presidency, and McKinley found himself in a position to restore to political dominance his cherished protectionist principles. Under his stewardship, Congress passed what was called the “Dingley Tariff,” after Ways and Means chairman Nelson Dingley, which buoyed tariff rates near the levels of the McKinley bill.

But McKinley also embraced a new doctrine designed to foster international trade where, in his view, domestic manufacturers were not harmed. He dubbed this new approach reciprocity, which essentially called for negotiating reciprocal tariff-reduction deals with other countries. Their goal would be to eliminate unnecessary trade barriers on both sides of trade deals—without generating fears of resulting trade wars. Bear in mind what was happening in America at the time. Agriculture and industrial production were exploding far beyond the domestic market’s ability to absorb U.S.-made products. U.S. exports were taking off. Meanwhile, America was pushing into the world, crushing Spain in the Spanish-American War and becoming an empire along the way. It built a navy, with naval coaling stations around the globe, to protect U.S. shipping. McKinley saw that the severe protectionism he had always advocated now stood in the way of American expansionism.

He negotiated major reciprocal trade agreements with various nations, including France. But Senate Republicans, led by Senator Aldrich, balked at ratifying them. After his 1900 reelection, McKinley decided to take the issue to the American people in a series of forceful speeches touting the need for targeted tariff reductions. On September 5, 1901, at the Pan-American Exposition at Buffalo, he declared, “Isolation is no longer possible or desirable.” Powerful advances in the movement of goods, people and information across wide distances, he added, had brought the world closer together, fostering more and more international trade. America, with its vast productive capacity, stood positioned to exploit this development like no other country. “Reciprocity,” he said, “is the natural outgrowth of our wonderful industrial development.” The next day, he was assassinated.

His successor, Theodore Roosevelt, abandoned McKinley’s reciprocity initiatives and hewed closer to the Republicans’ traditional philosophy. It wasn’t until the next Democratic president, Woodrow Wilson, that tariff rates were reduced once again. Wilson also fostered ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment, allowing a federal income tax and softening the country’s dependence on tariff revenue.

A CENTURY of back-and-forth over trade highlighted the country’s inherent political divide on economic philosophy, with sentiment roughly even. But the issue may not have been as significant as both sides believed. Washington Sen. John B. Allen argued during the McKinley-tariff debate that many other factors besides trade policy contributed to America’s economic growth. The country’s history, he said, showed that “prosperity and adversity have come alternately under both a high and a low tariff.”

Allen had a point. The United States was a young and lively nation, rich in resources and geographical advantages, populated by a vibrant and expansionist people, powerfully positioned upon the American continent, facing two oceans. Its destiny seemed secure irrespective of fiscal policies at any given time or the political passions unleashed by the tariff issue. In any event, the Wilsonian approach prevailed through most of the 1920s.

Then came the Smoot-Hawley Tariff of 1930, which raised duties on some twenty thousand imported goods, in some instances to record levels. American economists had petitioned the president to veto the bill as economic poison. “Countries cannot permanently buy from us unless they are permitted to sell to us,” said the economists, echoing the views of that rustic Texan, Roger Mills, “and the more we restrict the importation of goods from them by means of even higher tariffs the more we reduce the possibility of our exporting to them.” The country was in the early stages of the Great Depression, and as its ravages upon the American people increased, the Republicans’ political standing plummeted. In the 1930 midterm elections, opposition Democrats took control of the House of Representatives with a gain of fifty-two seats. Two years later, with Franklin D. Roosevelt on the presidential ballot, the Democrats gained another ninety-seven House seats and twelve in the Senate. They came within a single seat of capturing the Senate. Hoover, on the ballot for reelection, didn’t crack 40 percent of the popular vote.

With Democrats now enjoying a commanding position in American politics, tariff rates began a steady decline that would last for decades. The free-trade consensus became clear. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was established in 1947 to reduce trade barriers and promote unfettered trade among capitalist nations. In 1995, that organization became the World Trade Organization. This ideology of open markets and low tariffs dominated worldwide following the fall of Communism.

But that was after the 1970s and 1980s, when hard times for domestic manufacturers generated protectionist calls from beleaguered industries and organized labor. A synthesis of sorts emerged after Detroit automakers and the United Auto Workers jointly sought protection from Japanese imports. Reagan rejected high tariffs in favor of voluntary restrictions based on quotas arrived at through diplomatic agreements (not unlike McKinley’s reciprocity concept). But this led Japanese automakers to import larger, more expensive cars into the United States, thus getting into the more lucrative upper end of the car market. Eventually, Japanese automakers moved their factories to U.S. soil, thus manufacturing their cars with American labor to leaven protectionist pressures.

Meanwhile, the impetus for free-trade agreements grew, leading to Reagan’s Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement of 1987 and to President Bill Clinton’s far more momentous North American Free Trade Agreement of 1994, called NAFTA. This far-reaching legislation brought together a coalition that included a center-left Democratic president bent on “triangulating” major issues to capture a wide swath of moderate voters, a GOP dedicated to reducing barriers to commerce wherever they could be found and a U.S. electoral majority. Only organized labor seemed to be the odd man out. Free trade had never been so thoroughly entrenched in American politics.

But developments were percolating in American society that would render this consensus temporary, as indeed every political consensus is. The man who perhaps best personified these developments was conservative commentator and gadfly presidential candidate Patrick J. Buchanan. As a lifelong conservative and zealous supporter of Reagan, whom he served as communications director from 1985 to 1987, Buchanan thoroughly embraced the free-trade outlook. Indeed, when presidential speechwriter Ben Elliott wrote that rousing free-trade address that was deep-sixed by White House Chief of Staff Donald Regan in the fall of 1985, Pat Buchanan was his boss—and cheered him on as he drafted the speech.

But after leaving the White House, the pugilistic conservative experienced a conversion when he visited an uncle in Pennsylvania’s Monongahela Valley, prosperous iron and steel territory for decades before falling on hard times. “Why are you supporting this free trade?” asked the uncle. “Don’t you know what’s happening to the Mon Valley?” Buchanan looked around and saw that his uncle was right when he said, “The Mon Valley is dying.” Imports were killing it. “The more I read of local businesses and factories shutting down, workers being laid off, towns dying as imports soared,” wrote Buchanan later, “the more I began to ask myself, The price of free trade is painful, real, lasting—where is the benefit other than the vast cornucopia of consumer goods at Tysons Corner?”

In his presidential bids and writings, Buchanan became the champion of those working-class Americans caught in this tightening vise. He soon discovered that he was “trampling on holy ground,” as he put it, adding: “For some conservatives, to question free-trade dogma is heresy punishable by excommunication.” But he wondered why conservatives should despise protectionism when protectionism had been the policy of their Republican Party for nearly seventy years after 1860—and of its forerunner parties, the Whigs and Federalists, for sixty years before that. Protectionism was part of the party’s heritage, he concluded, and now the plight of the country’s working class required a return to that heritage. His focus would be those working families of America ravaged by the obliteration or decline of the country’s manufacturing base.

THAT IS the focus also of Donald Trump, whose rhetoric on trade sounds as if it were pulled straight from Buchanan’s book on the subject, The Great Betrayal. Trump’s political success thus far, and its fallout here and abroad, reflect the reality that we are moving into a new era on trade. Trump’s free-trade attacks, like Buchanan’s, jibe with his attacks on globalism, open borders, humanitarian interventionism in foreign policy—and the American elites who have fostered these policies.

This new mood is a death knell for the proposed twelve-nation Trans-Pacific Partnership, designed to usher in a new generation of free-trade deals. Even the Democrats’ presidential candidate, Hillary Clinton, now opposes this initiative, which she once hailed as “the gold standard” in such policy concepts. It was also thoroughly in line with her husband’s free-trade philosophy. Now she sees the handwriting on deteriorating factory walls.

This is not the 1980s, when presidential aide Ed Rollins could create a tempest in a teapot over trade policy in a free-trade administration struggling merely to tamp down pressures for protectionist measures in a fundamentally free-trade era. This is more like the 1790s, 1820s, 1890s and 1920s, when protectionism played a major role in U.S. policymaking. Hamilton, Clay, Lincoln, McKinley and Hoover are back.

Robert W. Merry is a contributing editor at the National Interest and an author of books on American history and foreign policy.

Image: 1896 William McKinley campaign poster. Wikimedia Commons/Public domain