Don't Exile Thucydides from the War Colleges

War games aren't a perfect tool for teaching strategy.

Last month at War on the Rocks, Marine War College professor Jim Lacey held forth on how to teach Thucydides. Read the whole thing and hurry back!

Let’s congratulate Professor Lacey for raising awareness about professional military education and the value of gaming at war colleges. Readers of his missive, however, could be forgiven for coming away with the impression that war colleges not named Marine teach the Peloponnesian War almost wholly through passive methods such as lectures: students come to class, a professor drones on for the allotted time, there’s a perfunctory Q&A, they go away. That’s what Lacey says he did when starting at Quantico a few years ago. Ergo, it must be what other military education institutions do.

Now let us give you a view from Newport, where the picture differs radically from the one Lacey paints.

Having afflicted our students with a passive learning experience, opines Lacey, we benighted old-timers are “fooling” ourselves if we believe they come away knowing “anything about Thucydides besides reciting the mantra ‘fear, honor, interest.’” Oh, and they might remember that “attacking Syracuse was bad,” even though “there were a number of good strategic reasons for Athens to attack Syracuse.” Who knew there was sound logic behind the Sicilian expedition? “Certainly not any War College graduate over the past few decades.”

Thankfully, along comes Jim Lacey to save a complacent war-college professorate from our “mentality” that “things are fine as they are.” There’s just one problem with his tale of discovery and redemption. We and our illustrious predecessors in Newport have been teaching the Peloponnesian War for forty-plus years, since Adm. Stansfield Turner, then the president of the Naval War College, instituted a curricular revolution.

And never since 1972 have the faculty taught Thucydides—or any other segment of the strategy courses—solely through lectures. While lectures are used, they are but one element in the course of instruction. Their purpose is to fuel thought and debate in seminars while helping students compose essays wrestling with strategic problems.

Readings comprise another major element of the strategy courses. Students and faculty explore the strategic canon—Clausewitz, Sun Tzu, Mahan, Corbett, Mao—of which Thucydides forms a part. They then harness the big ideas gleaned from the greats to analyze a series of historical case studies. Lacey maintains that war-college students can’t read all of Thucydides’ History. Not so. They’ve done so for decades in Newport, therefore they can.

Indeed, reading the whole thing represents the basic, minimum, irreducible requirement for teaching the Peloponnesian War effectively. And, because Thucydides thoughtlessly neglected to carry the story down to Athens’ fall in 404 BC, we assign another primary source, Xenophon’s Hellenika, to complement Thucydides’ chronicle. A few secondary selections to complement Thucydides and Xenophon, and we’re set for the writing of essays and for informed discussion in seminars.

Essays are another vital element of learning about strategy. Some students present essays in seminar each week, exploring topics listed in the course syllabus that the professors want to examine in depth in class. Yes, there is a question in our syllabus about the efficacy of invading Sicily. The Sicilian campaign constitutes just a fraction of the topics we examine in Newport. There’s far, far more to the Peloponnesian War than the Sicilian debacle.

For instance, we draw upon Thucydides to examine enduring yet pressing strategic problems. Among them are offshore-balancing strategies; quandaries confronting democracies making policy and strategic decisions during long wars; coalition management; methods for balancing resources and risks among different theaters of operation; defense of a maritime system (marked by trade, wealth and political openness) from fearful challengers; the repercussions when a sea power loses command of the maritime commons; command leadership in wartime; and the moral and ethical dilemmas confronting countries under severe security threats. This rich menu feeds the students’ appetite to know more.

Tutorials have long been part of the strategy courses in Newport, providing an opportunity for one-on-one contact with students. Naval War College students develop a paper over a two week-span. Before the essay’s due date, the writer meets with the seminar professors, bringing a formal outline for the paper. The professors probe the content and logic flow of the paper, and generally demand that the student defend or refine the approach before finishing the essay.

And lastly, every essay goes out to the entire seminar the day before class, becoming part of the required readings for the week. Professors typically integrate the essay into classroom debate and discussions, usually by getting the author to give a short “so what” assessment, applying what he or she has learned and then subjecting the paper to critiques from the professors and fellow students. These essays are graded, with the faculty providing line-by-line feedback on student writing and reasoning.

Lacey says, “Trust me, no one likes having their answers critiqued, least of all Type A colonels.” That may be true, but our students are seasoned professionals. They don’t throw hissy fits when they are graded because they respect the effort made by the faculty to provide feedback, as well as the grading system’s credibility and integrity. (Appeals of grades are few and far between.) While writing these essays makes heavy demands on the students, they are more than up to it.

Then there are seminars, another element of the strategy courses and the capstone event for each week. Seminars are not lectures or monologues. Professors are there to raise important problems in strategy, help students use ideas from the strategic canon to think through these issues, and correct errors of fact that may come up during discussions. (The Germans did not bomb Pearl Harbor, for example.) There are no “school solutions,” or party lines, in Naval War College strategy courses.

Each element of the course equips students to think for themselves without indoctrinating them in what to think. We encourage them to take issue with professors as well as one another. That intellectual free play prepares them to act as effective devil’s advocates in real-world debates, dispelling the groupthink that can inhibit creativity and dynamism in armed forces and civilian agencies.

For what it’s worth, strategy professors conduct formal debates about the merits, dangers, costs, risks and feasibility of the Sicilian adventure. One team is assigned to argue that the expedition was a bad idea, full stop. The other argues that it was a sound idea badly executed. Each side presents its brief, each side gets to rebut the other, and then—unless the debate breaks into a mêlée, which is far from unusual given the liveliness of Newport seminars—the seminar holds a vote to determine the victor.

The “it was a good idea, badly executed” team wins about half the time, in part because one of the greats of maritime strategy makes a similar case. So much for the claim that Thucydides’ treatise gets bowdlerized to gee, attacking Syracuse was bad.

And that, in a nutshell, is how the Naval War College employs Thucydides to teach strategy. To recap: the strategy curriculum in Newport is all about critical analysis of historical cases. It involves reading primary and secondary sources, listening to lectures, and then convening to use strategic ideas and historical fact to test operational and strategic alternatives taken and foregone.

So it’s false to maintain that the professorate can’t expect military officers and national-security professionals to read classic accounts on war such as Thucydides’ History. We do it with considerable success, as evidenced by our students’ achievements, of which they are justly proud.

Now Lacey is to be congratulated, too, for arguing the value of war games as part of a war-college experience. No one, of course, would deny the value of gaming as a tool for assessing the feasibility of operations and testing doctrine. As Clausewitz long ago highlighted, war is concerned with assessing probabilities of outcomes. Gaming can help assess those probabilities for operational success and failure. By gaming a scenario a number of times, a planner can gain an understanding of the likelihood of success for a projected operation.

During the interwar period, over many years, students at the Naval War College gamed different scenarios. On the gaming floors of Newport, imaginary battles were fought by the United States (Blue) against Britain (Red), as well as against Japan (Orange). War games have thus long provided a tool for operational learning and experiment.

Education, however, is filled with tradeoffs. Should students read Thucydides, or spend the time that could have been spent reading Thucydides learning the rules for a game on the Peloponnesian War—a game they might never play again? Of course, in a world of no constraints, you can do both if you have the luxury of plenty of time. If you’re forced to choose, the primary sources must come first.

The problem is that time is a tyrant. Time is in great shortage during an officer’s career. It cannot be wasted. Today, the pressure is to shorten the time officers spend at war colleges—not expand it. Gone forever are the days between the world wars when Raymond Spruance served for four years at the Naval War College, first as a student and later on the faculty. While today’s U.S. Navy looks back with reverence on the interwar years, it no longer subscribes to personnel policies that produced the victor of Midway and the Philippine Sea.

Nor should we in looking back to the historical record conclude that gaming is a panacea for solving complex strategic problems. Many examples can be adduced to show the limits of gaming. All too often, the results of games are corrupted when they are used to support entrenched doctrine, bureaucratic inertia and sacred budgetary priorities. It’s all too common to replay a game that produces unsatisfactory results: rejigger the assumptions underlying the game until it yields more congenial results.

Rather than liberating the thinking of those who play, then, war games can be abused by participants and onlookers who do not want to challenge conventional thinking, but instead want to propagate a party line. Such games confirm what the leadership wishes to confirm—and leave the service ill-prepared for thinking, determined foes bent on thwarting America’s will.

Games can miss future challenges, furthermore, if the game designers are lacking in vision and tied to conventional scenarios. Before the First World War, gamers at Newport played over and over again scenarios for a conflict with Black (Germany). The games provided the basis for the famous Black War Plan. What did the games conclude? They envisioned a German projection of a battle fleet across the Atlantic that would seize forward bases in the Western Hemisphere, bring the American fleet to battle and impose a blockade on the eastern seaboard of the United States.

These games captured a reality that never came to pass, and wasn’t very likely to. The war that the United States actually did fight was far different from what the gamers played. There was no decisive big-ship showdown pitting the American battle line against a German high-seas fleet; the U.S. Navy fought as part of a coalition with other countries; defense of transatlantic sea lanes against submarines proved to be the navy’s most demanding mission; and the United States ended up deploying two million boots on the ground to the battlefields of France to attack Germany’s army. And for all the virtues of the touted Orange games of the interwar era, they did not envision the employment of nuclear weapons against Japan.

It’s also highly misleading to hype the role of war gaming in naval officers’ interwar educational experience at the Naval War College. If all officers had done in Newport was replay scenarios for fighting against Orange, then the college would have signally failed in its responsibility to equip the minds of naval leaders with the intellectual tools and frameworks for analysis that should be a prerequisite for higher command. At the college, students heard lectures, read extensively, discussed tactics and strategy, and wrote essays—much as they do today.

Indeed, a perusal of Adm. Ernest J. King’s thirty-page thesis on strategy shows that he invested considerable time in reading while attending the college. To write his strategy thesis, King, a future chief of naval operations, read the equivalent of a book a week. He recounts reading classics of strategy like Clausewitz, Mahan and Corbett, as well as works then in vogue on American foreign policy, civil-military relations, high command in wartime and the history of the Great War.

King wrestled with these works and the problems of strategy that they raised. Today’s students need to do so as well and not be told that there is some shortcut to strategic literacy and competence. Games are no substitute for reading and thinking. Games are invaluable when well-educated officers, officials and scholars play them.

If students are not reading the equivalent of a book a week at a war college, then they are not receiving an education adequate to help them take part in the realm of strategic decision-making. Civilians, national-security professionals and military fellows attending graduate-level educational institutions on strategic studies and international relations like Georgetown, Columbia, the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies or the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy are capable of carrying a heavy workload of lectures, reading, seminars and essays. Why, then, are war-college graduates unable to do likewise?

As professional educators, we would be letting down our students if we do not prepare them with disciplined habits of thought that are the products of a rigorous education. We believe in investing in the intellectual development of those in the profession of arms, to include a heavy dose of reading, writing in-depth analyses on complex problems, and grading that informs the students about how to improve their skills in thinking and communicating.

To be a professional entails lifelong learning, requiring a commitment of time to study in preparation for action. This investment in our people’s capacity to think before they act is nothing less than a national strategic imperative. And it’s an imperative we’ve been pursuing through time-tested methods—for generations.

Jim Holmes is Professor of Strategy at the Naval War College, and John Maurer is the Alfred Thayer Mahan Professor of Sea Power and Grand Strategy and served as the Chair of the Strategy and Policy Department. The views voiced here are theirs alone.

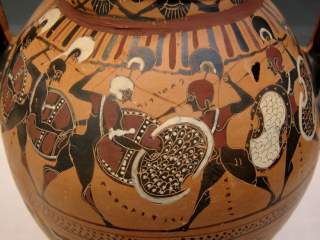

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Public domain