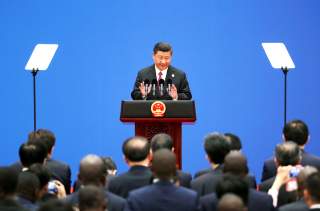

How China Is Trying to Dominate the Middle East

But will it work?

Tensions between the United States and China seem to be defining the bilateral relationship between the two countries these days. From a growing trade war to the Trump administration’s characterization of China as a “strategic competitor seeking to undermine U.S. power and influence” in its 2017 National Security Strategy, political and economic relations appear to have settled at a recent nadir.

But great power competition between the two most powerful militaries and economies is not geographically limited. China is indicating its intent to shape the Middle East’s regional and military landscape through trade relationships with regional states as well as through projection of its own military might. Below are three areas to watch where China’s more assertive Middle East engagement may lead to tensions with America.

Iran Becomes the Focal Point of the Trade War

Crude oil is a key strategic, imported commodity for Beijing, and the Middle Eastern states trail only Russia as supply sources for China. As the world’s largest petroleum consumer with declining domestic petroleum production, China aims to expand its refining and storage capacity to decrease its exposure to global energy market volatility. The U.S. goal of bringing Iran’s crude exports to zero threatens China’s import-based strategy, and all indications are that Beijing—Tehran’s top importer—will duly ignore the sanctions and continue business more or less as usual. Iran also figures to be a linchpin in China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), with Chinese infrastructure investment in Iran totaling $8.5 billion in loans from the Export-Import Bank of China through early 2018.

As full secondary sanctions on oil are re-imposed in November, Iran threatens to become the focal point of the looming U.S.-China trade war, with potentially grim implications. Oil prices are likely to climb in 2019 as Iranian oil comes offline, resulting in higher costs for downstream products, although it is possible the effect will be a wash for the U.S. economy.

Furthermore, because Iranian oil purchases run through the sanctioned Central Bank of Iran, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) would be subject to U.S. secondary sanctions. The PBoC could respond with a raft of asymmetrical options for retaliation, including devaluing the renminbi, targeting U.S. companies with retaliatory regulations, or the nuclear option—selling some of its $1.2 trillion in government-held U.S. treasury bonds. Already, broader trade tensions and the threatened imposition of tariffs on U.S. oil imports earlier this month have discouraged Chinese purchasers from buying U.S. crude. Considering the factors at play, the November secondary sanctions deadline could become a flashpoint for further tensions.

Chinese Tiles in the Gulf Mosaic

Economic engagement and security relationships are key facets of China’s engagement with the Arab Gulf states. China tries to leverage business to balance tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran. For example, China overtook the United States as Saudi Arabia’s largest trading partner in 2017, making it the key trade leader with both Iran and Saudi Arabia. In 2017, Saudi Arabia’s King Salman signed $65 billion-worth of memorandums of understanding in Beijing, and the two countries began implementing agreements in petrochemical, technology, and other sectors. Moreover, Saudi Arabia also courted China as a host for the now-shelved Saudi Aramco. However, rising prices led China to decrease its Saudi crude imports in 2018.

China is wary of veering too closely to Saudi Arabia or Iran at the risk of alienating the other, and one fundamental question will be whether the Chinese build on already high rates of cross-investment with the kingdom as secondary sanctions against Iran are re-imposed. Chinese diplomats have tried to draw linkages between the BRI and Vision 2030 plans, although concerns over opaque Saudi government regulation may limit Saudi-Chinese cooperation. Also, the Trump administration’s apparent willingness to broach a nuclear deal with the kingdom also may have created a leverage point in America’s favor.

Beyond Saudi Arabia, Beijing pledged $23 billion in development aid to the region during the China Arab States Cooperation Forum. Chinese president Xi also visited the United Arab Emirates last month to discuss economic cooperation and regional security. This is because as much as 60 percent of China’s trade with Europe and Africa passes through the UAE. Additionally, China’s relations with the Gulf states are economically promising and could suggest a growing acceptance of Beijing’s influence.

Militarily, the Chinese have recently increased naval patrols near the Gulfs of Oman and Aden. Beijing has also established a base in Djibouti with an eye to protecting business and trade interests in the area and perhaps a longer-term military buildup. China could also play a constructive role in maritime missions like counter-piracy or anti-smuggling, although the United States and its naval forces at CENTCOM will surely be monitoring developments closely.

However, Beijing’s willingness to deal with Tehran may prove problematic for cooperation in the security sphere, even as China ramps up its regional military presence. China’s relationship with Iran has prevented it from getting as close to Arab states as is necessary to pose a challenge to the United States as the region’s dominant security force. So long as Beijing remains close to Tehran, it is unlikely Saudi Arabia and the Gulf will turn to China for more than occasional purchases of drones, special ops gear, and other military hardware in the short-term.

Russia and China: Competition or Cooperation?

Russia’s role as another external power in the region vis-a-vis China is also worth examining. Moscow seized the great power driver’s seat in Syria, where it has attempted to de-escalate tensions between Israel, Iran, its proxies, and the Assad regime along the country’s southwestern border. Its success in that endeavor has been questionable, but Putin’s supposed mediation between the Iranians and Israelis has become a Kremlin talking point.

China has acted largely in concert with Russia in Syria, continuing to support Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and engaging in diplomatic obstructionism against intervention at the United Nations since the civil war’s early days. While China could potentially play a significant role in Syria’s reconstruction, it remains unclear if Beijing is willing to do so.

China and Russia’s support for Iran is likely to remain within limits—it’s unclear whether either country would genuinely support Iran's admittance to the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, for example—but Tehran policy will remain a lever for both countries to push should they want to pester America.

The BRI will prove an interesting space to observe broader Russian-Chinese dynamics. China’s infrastructure investment around the energy sector could bolster Iran’s ability to export liquified natural gas with the exit of European companies, though secondary sanctions will hamper Iran’s prospects for entering European markets. Russia is satisfied with this status quo and will try to keep Iran’s LNG flowing eastward to maintain its stranglehold over Europe. This arrangement ostensibly suits both Moscow and Beijing. At the same time, however, China is using Iran to develop BRI routes that circumvent Russian territory, leaving Russia in the cold for some of the Belt and Road benefits.

There are several takeaways for the United States. Iran’s political factions are likely to converge under the Trump administration’s rhetorical and financial assaults, and continuing support from China could undermine the overarching U.S. policy goal of containing Iran’s efforts to exert its influence in the region. Though U.S. Iran policy, among other factors, may draw support from like-minded regional partners, America may risk escalating economic conflicts with China as the price of re-imposing secondary sanctions. From a strategic perspective, America must also consider whether removing Iran as an alternative source of energy—in particular, natural gas—for Europe actually benefits Russia and hinders the objective of uniting European allies against the Kremlin.

Given Washington’s focus on the Indo-Pacific as the primary theater of both economic opportunity and tomorrow’s great power conflicts, the Trump administration may need to ask itself if this is the fight with China that it wants to pick.

Owen Daniels is an associate director with the Middle East Security Initiative in the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security. He is also an Assistant Managing Editor at Young Professionals in Foreign Policy’s Fellowship Program. Follow him on Twitter: @OJDaniels.

Image: Reuters