How to Respond to China in Africa

Think economics, healthcare, and good governance.

The murder of the Washington Post writer Jamal Khashoggi has finally prompted the leading U.S. media sources to take a hard look at the Yemen War in all its putrid odor. It seems that the killing of a journalist may change the “arc of history,” so perhaps there is a silver lining to Riyadh’s despicable deed. Should the media dare to ask some hard questions about the involvement of the U.S. government and various American corporations in that horrible conflict, they, unfortunately, will have much to discuss. The catastrophe of the Yemen War should be the last nail in the coffin of major U.S. involvement in the Greater Middle East. Before the 1980s, there were no major, permanent U.S. military deployments into the Middle East and Central Asia and America should return to the infinitely wiser and more cautious approach of “offshore balancing.”

In Africa, the mistakes have been smaller, but just as obvious. It was not journalists who were killed, of course, but American servicemen. Andrew Bacevich recently commemorated the brave Americans who died in the bloody 1993 Battle of Mogadishu, suggesting that if we had really grappled fully with the lessons of that tragic day that many subsequent interventions—however, well-intentioned—could have been avoided. Yet, the United States is still stubbornly constructing a large drone facility in Niger a year after four U.S. special forces soldiers were slain in a badly botched “security cooperation” mission nearby. Does anyone think that Niger constitutes a vital interest of the United States? Does anyone actually believe that the drone base in Niger will reduce terrorism in that volatile region rather than increase it? Hopefully, the Niger fiasco will continue to propel a reexamination (and indeed soul searching) regarding U.S. military commitments in Africa. However, a new and disturbing rationale is now increasingly put forward for the enhanced U.S. military footprint in Africa. The justification is—you guessed it—the Chinese bogeyman. To deepen the American understanding of Chinese activities in Africa, this Dragon Eye column will briefly discuss a few recent Chinese-language articles on the subject.

It is indeed true that China is ever more involved in Africa. And that involvement now includes a somewhat extensive security presence. Much has been said about the new Chinese military base in Djibouti. There has been finger-pointing and apparently laser-pointing too. There is the accusation that Chinese observers might gain by watching U.S. Navy ships come in and out of the port. It might occur to those of a less paranoid sensibility that China will be vulnerable to the same kind of snooping (or even laser-pointing if necessary), and moreover that Beijing would not likely set up a base next to several Western countries’ bases if it had something nefarious to hide. Indeed, most of the Chinese military presence in Africa has long been under “blue helmets” as United Nations peacekeepers. As such, Chinese soldiers (mostly engineers, transport experts, police and medical staff) have been sent into some tough situations, from western Morocco to Mali to South Sudan. Not long ago, two Chinese peacekeepers were slain in South Sudan, while another was killed in Mali. A mid-2018 analysis in the Chinese journal International Politics [国际政治] concludes that UN Peacekeeping is plagued by a “leadership ability vacuum [领导力真空]” since America and other Western countries do not take a very active role. “Yet UN peacekeeping has great significance for China [然而, 联合国维和对于中国侧具有非常重要的意义].” The author advocates that Beijing take a stronger leadership stance in UN peacekeeping, and African peace and security building should benefit from “more … effective Chinese planning.”

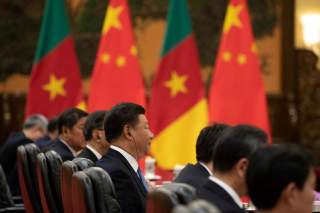

A whiff of the new cold war between the United States and China is already perceptible in some Chinese writings on Africa, at least to a small degree. A September 2018 edition of the CCP Central Committee magazine Contemporary World [当代世界] that was published during the important Seventh Forum on China Africa Cooperation meeting in Beijing, carried a lead editorial that seemingly builds China-Africa friendship on the basis of a shared historical bitterness toward the West. The third sentence of the editorial observes that “China and Africa have both endured the struggle against imperialism, against hegemony, and against the extreme hardship of colonialism … [中非都经历 .… 反帝反霸繁殖民的艰苦卓绝斗争].” Both China and Africa are characterized as having jointly experienced “oppression and humiliation,” but their societies also are said to have different values than the excessive individualism of the West, moreover. The editorial concludes that the “international situation is becoming much more complex” and then goes on to suggest that China-Africa partnership is, therefore, more “necessary.”

While this new tone is somewhat troubling, it may be inevitable as a genuine cold war haunts U.S.-China relations. Still, it would be a massive mistake to view China’s activities in Africa through a military or security lens primarily. The majority of evidence, by contrast, suggests that economics and enhanced business opportunities are behind China’s initiatives in Africa. As a sign of a very different approach to Africa (compared with the West), a detailed article appeared in one of China’s most prestigious social science journals in early 2018 entitled: “Economic Miracle in Africa: Driving Factors and Long-Term Growth.” Among the many factors cited in this report behind Africa’s current economic success include: “continuing reduction in wars … implementation of macroeconomic reforms … enhanced political and economic stability … increased capital inflows … consumption growth … increased investment [and] …. transfer of labor from agriculture …” The report is replete with graphics that even track the continent-wide reduction in military conflicts and the increasing number of democracies. One impressive chart compares anemic growth in the 1990s with periods of tiger-like growth after 2000 in Congo, Ethiopia, Cote D’Ivoire, Angola, and Sierra Leone. Still, this report does not white-wash future problems and does conclude that “low capital accumulation is the major obstacle to long-term economic development [资本积累是长期经济发展的主要障碍].”

If the report above is somewhat clinical, the stellar magazine Chinese National Geography [中国国家地理] carried an in-depth article on East Africa in the September 2018 edition. This article claims that over 2017-18 East Africa has emerged as the “locomotive [火车头]” of African economic growth with region-wide growth averages likely to surpass 6 percent in both years. The reporter visits Rwanda and is impressed by the country’s adoption of China’s economic strategy from decades ago that emphasizes labor-intensive industries. Observing that many Chinese entrepreneurs might be attracted by the lower startup costs in Africa, the article ends by daring to ask whether perhaps “in the future, will Africa become the ‘factory of the world’ [未来非洲会变成 ’世界工厂’吗]?”

If China’s perception of Africa could be a bit too rosy, the American viewpoint is likely too dark and cynical, unfortunately. One may ask how a catalog of “micro-aggressions” on the other side of the planet ends up being a front-page story in the New York Times recently. Racism exists anytime cultures are coming into close and extensive contact, especially when this a relatively new phenomenon. Westerners should know that better than most. This story is probably the highly regrettable impact of our “leading journalists” being addicted to Twitter. But let’s focus here on matters of real importance, such as people starving or getting killed in wars. The Niger fiasco mentioned in the introduction to this essay is sadly hardly the worst case of American malpractice in African diplomacy. A recent report suggests that the death toll from the civil war in South Sudan has now reached 380,000, a proportionally higher segment of the population than in Syria. This report explains: “South Sudan is a rare test case of the United States midwifing a country into existence, trying to help create a new democracy from scratch.” Then, there is the $14 billion in aid that the United States gave to that specific region since 2005, according to that same report. It is admitted that this major U.S. investment yielded, in the end, “a failed state.” Unfortunately, South Sudan appears to be yet another example of chaos and catastrophe wrought from the “hell of good intentions.”

Washington’s Schadenfreude for Beijing grows ever more acute and is on full display in Africa. In addition, this unflattering approach seems to infect the American attitude to the “Belt and Road” Initiative more generally. Such an insecure and paranoid outlook is hardly befitting of a true, capable superpower. America has indeed chalked up very significant achievements in Africa, whether the Bush-era outstanding initiative to fight the AIDS epidemic or Obama’s excellent response to the Ebola Crisis not long ago. Instead of “seeking out monsters to destroy” in Africa or bemoaning every Chinese initiative there, America should thoroughly demilitarize its approach and double down on fostering markets, education, environmental sustainability and good health. On many such worthwhile projects, Washington would do well to partner with Beijing.

Lyle J. Goldstein is a research professor in the China Maritime Studies Institute at the United States Naval War College in Newport, RI. In addition to Chinese, he also speaks Russian, and he is also an affiliate of the new Russia Maritime Studies Institute at Naval War College. You can reach him at [email protected]. The opinions in his columns are entirely his own and do not reflect the official assessments of the U.S. Navy or any other agency of the U.S. government.

Image: Reuters