From Jamaica with Love

For James Bond’s creator, Ian Fleming, Jamaica represented a colonial paradise where the sun had never set on British power.

Matthew Parker, Goldeneye: Where Bond Was Born: Ian Fleming’s Jamaica (New York: Pegasus, 2015), 400 pp., $27.95.

WHAT IS the secret of James Bond’s extraordinary endurance? Sixty-two years after he made his first appearance in a novel by Ian Fleming (and fifty-one years after the death of his creator), 007 still haunts our spy-novel dreams. John le Carré has sold a lot of books, and has sometimes come close to producing substantive literature, but his protagonist George Smiley never inspired mass obsession. And while Jason Bourne might offer a bit of competition when it comes to high-concept movie chase scenes, he can’t hold a candle to Fleming’s creation when it comes to theme songs, catchphrases or brand recognition. The whole point of Bond is that we know precisely what we’re going to get, and we’ll be mighty disappointed if we don’t. Shaken, not stirred. Submissive supermodels. Cars that put Google and Tesla to shame. Villains with shark tanks and neon names.

A lot of us would like to believe that we’ve outgrown this sort of thing. But Bond couldn’t care less. He just goes right on selling books and memorabilia and DVDs, and he certainly didn’t look obsolete when he parachuted into the 2012 London Olympics at the side of Queen Elizabeth II. Later this year, he’ll be turning up in Spectre, the twenty-fourth film in the Bond franchise; that number doesn’t include the knockoffs, the clones or the parodies, none of which has had anything like the staying power of the original. (The movies have grossed over $6 billion worldwide by now—and that’s not adjusted for inflation.) Easily dismissed as a glorified cartoon character, Bond turns out to have a surprisingly stubborn lock on the collective id. Every time we start congratulating ourselves on some new sensitivity class we’ve passed, Bond rises up to remind us: nothing beats making a debonair wisecrack in your tuxedo right after you’ve offed the bad guy.

BOND HAS become such a part of our cultural background noise that it comes as a something of a jolt to recall that he’s actually the product of one man’s imagination. One summer’s day in 1952, the frustrated British newspaper executive Fleming sat down at his typewriter to produce Casino Royale. It took him a few tries to get the opening right, but the final product has a campy irresistibility: “The scent and smoke and sweat of a casino are nauseating at three in the morning. Then the soul-erosion produced by high gambling—a compost of greed and fear and nervous tension—becomes unbearable, and the senses awake and revolt from it.”

The character shared many salient traits with his creator. Fleming, like Bond, was an alumnus of British naval intelligence during World War II. Both smoked seventy cigarettes a day, consumed Churchillian quantities of alcohol and exulted in the fleeting assignation. (With characteristic obliviousness, Fleming put this observation in the mouth of one of his female characters: “All women love semi-rape. They love to be taken.”)

Both men were widely traveled, multilingual and strikingly xenophobic. The Japanese have “an unquenchable thirst for the bizarre, the cruel and the terrible.” The Chinese are “hysterical.” Italians are “bums with monogrammed shirts who spend the day eating spaghetti and meatballs and squirting scent over themselves.” Afrikaners are “a bastard race, sly, stupid and ill-bred.” In From Russia with Love, Bond’s Turkish colleague Darko Kerim makes the following observation about his own countrymen: “All this pretense of democracy is killing them. They want some sultans and wars and rape and fun.” There can be little doubt that he’s speaking for Fleming. “All foreigners are pestilential,” was another pearl from Bond’s inventor, in a letter to his wife in 1956.

None of which, of course, helps to explain why Bond became one of the most successful literary creations of the twentieth century, comparable in his mass appeal only with those other standouts of the British pop-culture pantheon, Sherlock Holmes and Harry Potter. How did Fleming come up with the formula? In Goldeneye, his new contribution to Bondology, Matthew Parker focuses our attention on a hitherto somewhat neglected ingredient of the concoction: the Caribbean island where 007 was born.

FLEMING FIRST visited Jamaica in 1944, when he attended an Allied policy conference on the island in his capacity as a senior officer of the Naval Intelligence Division. Instantly smitten with the place, he vowed to come back as soon as the war was over. He made good on his pledge surprisingly quickly. In 1947, he spent two thousand pounds on a nice plot of land overlooking the ocean on the as yet relatively pristine north shore of the island; soon after that, he spent the same amount on the construction of a no-frills bachelor pad that he named “Goldeneye,” the code name of one of the covert operations he’d worked on during the war. Once the house was finished, Fleming, who had managed to wrangle an annual two months’ vacation from his employers at the Sunday Times, spent every summer on the island. And it was during these summers, starting in 1952, that he wrote the books.

Jamaica flavors the world of Bond in some obvious ways. Many scenes in the books take place in Caribbean settings. The plot line for Live and Let Die reflected, in somewhat exaggerated terms, the political links between black civil-rights activists in prewar Harlem and the rise of black-power movements on the island. Fleming’s passion for diving (and his intimate familiarity with sharks) can be traced back to long hours spent swimming around the coral reef directly beneath his property.

Yet Parker argues that Bond’s birthplace had subtler effects as well. Bond may loom large as a Cold War creation, but the era of postwar austerity back home in England was, at first, equally important. England ended the war virtually broke, and shortages of basic goods and foodstuffs continued for years. (Meat rationing ended only in 1954.) A scene in Dr. No, set in a fictional version of one of Fleming’s favorite clubs in Jamaica, played on this theme: “Yes it was paradise all right, while, in their homeland, people munched their spam, fiddled in the black market, cursed the government and suffered the worst winter weather for thirty years.” The Labour Party’s electoral landslide in 1945 ushered in the nationalization of broad swathes of British industry and the creation of the cradle-to-grave welfare state—anathema to people of Fleming’s posh background. (His grandfather was the inventor of the modern investment trust.)

Jamaica offered obvious antidotes: sand, sun, plenty of booze and a constant stream of fresh local delicacies. Bond’s creator couldn’t help but adore the tropics, and he exulted in the island’s rich flora and fauna. One of the most intriguing revelations of Parker’s book is that Fleming emerges as a full-blooded naturophile. One surefire mark of a truly evil Bond villain is the gratuitous slaughter of birds or other wildlife. That makes a neat fit with the wonderful detail that Fleming borrowed the name for his most famous character from none other than an ornithologist. The real James Bond was the author of the leading field guide on birds of the West Indies.

THE ISLAND had other attractions. Jamaica’s social system remained complacently colonial. Jamaica had been a British possession for three hundred years, and in the immediate postwar period the imperial bureaucracy and the old British plantocracy continued to hold sway. (Parker refers to the island as “stuck in a comfortable time warp.”) The locals, by and large, still “knew their place”: even in the 1950s it was still possible to look past the rising Jamaican nationalist movement that was beginning to push for independence. When Jamaican journalist Evon Blake tried to strike a blow for racial equality by going for a swim at a resort in 1948, the managers of the place had the pool drained and refilled. The pound sterling still reigned—a not unimportant detail, considering the British currency’s weakness outside of the empire.

The Britishness of Jamaica mattered a great deal to Fleming—as it did to his best friend Noël Coward, who also bought property on the island. Like many other Old Etonians, Fleming was deeply distressed by the “twilight of empire.” The anxiety of the déclassé is a constant undercurrent in his novels, where Bond explicitly functions as the embodiment of the United Kingdom’s ability to punch above its weight despite its waning status. “They have no understanding of the [espionage] work,” Bond sneers about the Americans in From Russia with Love. “They try to do everything with money.” In one of his travelogues Fleming describes “washing the filth of the United States currency off my hands.” Jamaica and other British territories in the Caribbean are depicted as no-go areas for the Americans—a refreshing change, apparently, from the rest of the free world. One critic, correctly noting Fleming’s desire to create a character that would compensate for his country’s diminished role in the world, famously called Bond a “one-man Suez task force.”

The gadgetry fetishism of Bond’s universe feeds on the same impulse. The character of Q, the chief geek of the Secret Intelligence Service, recalls the wartime boffins who came up with world-beating inventions like radar and code-cracking computers. Fleming is determined to show that British ingenuity—a fruit of the ethos of “effortless superiority” celebrated by the public-school system—can still hold its own, even in a world dominated by big-spending Americans. The Cold War had reduced Britain to the role of a minor auxiliary of the United States—a sense reinforced, to particularly humiliating effect, by the scandalous news of the disappearance of Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess in the summer of 1951, two card-carrying members of the British establishment who were later revealed to have been serving as Soviet spies, along with Kim Philby and Anthony Blunt. The disgrace of their defection hangs like a shroud over the birth of Bond.

What comes through quite clearly in Parker’s account is that Bond’s creator had a very precise notion of the confection he was trying to produce. Fleming called his formula “disciplined exoticism.” He always made a point of sending his hero off to enticing locales, like Istanbul or the French Riviera, while steering away from destinations that might have seemed, well, overly Third World–ish. Fleming was fully aware of the escapism his readers craved: “The sun is always shining in my books,” he once remarked. Moonraker provoked some angry feedback from a number of his fans, who objected to the book on the grounds that it was set almost entirely in the United Kingdom. Fleming always strove to maintain a distinctly Caribbean note of sprightliness.

Yet his Bond is never tempted to go native. 007 is always his own man, always ineffably British. Cool self-possession triumphs, no matter how dangerous or alien or alluring the environment. And just when things threaten to succumb to the burgeoning outlandishness that Mike Myers captured so well in his Austin Powers movies, Fleming invariably rivets the story to reality with his surprising grasp of physical detail, a sharp note from the headlines or a bit of unabashed product placement. Fleming’s contemporary critics tut-tutted about his fondness for brand names; it’s a tic that wasn’t invented by the movies. Yet despite his high-style sheen, Bond is notable for his utter lack of aristocratic pretensions, and his consumerism roots him firmly in an age when class status is giving way to the meritocracy of the newly moneyed.

PARKER’S NARROW focus on Fleming’s life in Jamaica has its drawbacks. He offers only the sketchiest account of the writer’s life before the outbreak of World War II. Fleming’s wartime career in intelligence, so crucial to the imagining of his hero, barely gets a mention. Neither does Parker have much time for Fleming’s prewar career—or, more precisely, his nagging failure to find one. (At various moments he tried diplomacy, journalism, banking and stockbroking, never to much effect. It was the war that finally gave him direction and saved him from quotidian boredom.)

It might have helped if Parker had been willing to go into a bit more depth on these points, since the relative brightness of Fleming’s Jamaican interludes is hard to comprehend without complementary insight into the man’s extraordinary inner torment. He labored under the legacy of an absent father, who died a hero on the western front in World War I, and also from the meddling of his captious mother, who was still ordering him around well into his forties; his Jamaican refuge was, in part, a way of putting her at a distance.

And then there was the great love of his life, the aristocratic Ann (née Charteris). The two carried on an affair through her first two marriages—the first to Baron Shane O’Neill, who died in World War II, the second to Lord Rothermere, owner of the Daily Mail. When Rothermere finally drew the line and divorced her, it seemed only logical that she would respond by turning to the only man she had really loved for all those years. Yet her marriage to Fleming in 1952 seems to have marked the beginning of the end of their relationship. Fleming liked to claim that he had started writing Casino Royale in part to deal with the stresses associated with retiring from bachelorhood.

At home in London she cultivated a highbrow literary set that sneered at Fleming’s pulp fiction, and there are stories that have him sneaking up the stairs to avoid getting trapped in her late-night salons. She never really embraced Jamaica—an antipathy that seems to have deepened as she became aware of his local mistress, Blanche Blackwell—and Parker’s story correspondingly doesn’t capture all the highs and lows of their relationship. If you want to learn about the tragic life of the Flemings’ only son, Caspar, who committed suicide in 1975, you’re better off turning to Andrew Lycett’s excellent biography.

NEVERTHELESS, PARKER’S approach yields many valuable insights. If you want to appreciate Bond’s cosmos, zeroing in on the creative milieu that gave birth to him makes perfect sense. Fleming was a man of deep and often-toxic contradictions, and they emerged with particular clarity in his adopted home. He affected an air of clubbish nonchalance, but, as his boozing suggested, he also suffered from severe self-loathing and a poorly concealed death wish. He could be effortlessly charming when he felt like it, and he inspired intense loyalty among his friends—yet he could be gratuitously opprobrious, if not downright vicious, to those he saw no need to seduce. His relationship with Ann seems to have been founded on a shared proclivity for sadomasochism: “I loved being whipped by you and I don’t think I have ever loved like this before,” she confided to him.

Fleming also dreamed wistfully of a life of bohemian freedom even as he actively sought out the claustrophobia of stuffy clubs and high society. Patrick Leigh Fermor, one of Fleming’s many literary friends, nicely characterized the international jet set he encountered on the island: “Ice clatters in shakers and poker dice are thrown unceasingly on the bars of this Jamaican Nineveh, and, for the uninitiated visitor, the chasms of tedium yawn deeper every second.” To his credit, Parker is so good at bringing this world to life that you can understand exactly where Fermor is coming from.

It’s easy to make fun of Bond, and of our own fascination with him. But the truth is that his creator succeeded, where so few have, in producing a hero for a deeply cynical age. 007 is so vividly overdrawn that it’s easy to forget the traits that make him human. He may be a rake, but he does fall in love. For all his ruthlessness and implacability, he has a healthy hatred for the forces of chaos and totalitarianism. And he celebrates life and those who live it to the fullest.

Fleming certainly aspired to do the same, but he ended up dying at age fifty-six, consumed by his fondness for period vices. Bond, by contrast, shows little indication of leaving the stage. Once more, he’ll go on to die another day.

Christian Caryl is a senior fellow at the Legatum Institute in London and a contributing editor at The National Interest and Foreign Policy.

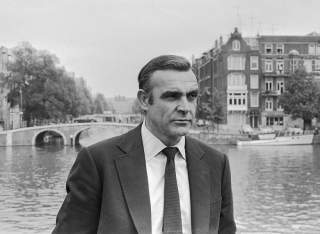

Image: Wikimedia Commons/Nationaal Archief