Battleship Sinks Submarine: How HMS Dreadnought Rammed and Sunk a U-Boat During World War I

After a chase that lasted only a few minutes—and almost involved a collision between Dreadnought and Temeraire—the former rammed U-29 and cut the submarine in half. U-29 sank almost immediately, taking all hands.

How many British dreadnoughts did German submarines sink in World War I? None. How many German submarines did the United Kingdom’s dreadnoughts sink? One.

Stories of naval technology in the twentieth century typically emphasize how the submarine and aircraft carrier rapidly displaced the battleship, despite the stubbornness of admirals who refused insisted on building more dreadnoughts. While there is an element of truth to this, especially in World War II, in the First World War both submarines and aircraft struggled to make inroads against the “castles of steel” that made up much of the most powerful fleets.

In March 1915, the U-27 class submarine U-29 began a cruise in the North Sea. U-29 was built in the months before the war started and had the most advanced design then available. Her captain was Otto Weddigen, who had commanded U-9 in 1914 and 1915, during which he executed one of the most successful attacks in the history of submarine warfare. On September 22, 1914, U-9 sighted three Royal Navy cruisers patrolling the eastern entrance of the English Channel. The Royal Navy did not take the submarine threat as seriously as it should have, and the three old cruisers had no destroyer escort. U-9 targeted and sank the HMS Aboukir, Hogue, and Cressy, killing over 1400 officers and men. From that point on, the Royal Navy took submarine attacks on the fleet much more seriously and radically improved its anti-submarine practices. Less than a month later, U-9 sank the even more elderly cruiser, HMS Hawke.

In the week before the encounter with the HMS Dreadnought, U-29 had sunk or damaged six Allied merchant vessels of over 17000 total tonnages. RMS Lusitania had not yet been torpedoed, and so German U-boat captains remained relatively free in their selection of targets. Weddigen was unusual in his preference for attacking warships, however. On March 18, U-29 encountered a portion of the Grand Fleet on exercise in Pentland Firth, in the Orkney Islands. U-29 fired a torpedo at the battleship HMS Neptune but missed. As was often the case with WWI submarines, the boat inadvertently broke the surface after firing the torpedo, which gave HMS Dreadnought and another battleship, HMS Temeraire, a chance to sight her.

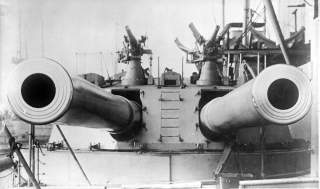

212 feet long with a displacement of 675 tons, U-29 was dwarfed by Dreadnought, which at 527 feet long displaced around 20000 tons. The HMS Dreadnought also had a speed advantage over the German submarine, even on the surface. Like many battleships of the period, HMS Dreadnought had a ram bow, although expectation that battleships would ever be able to use their rams in combat effectively had diminished as the quality of long-range gunnery improved. Indeed, all Royal Navy battleships would have such a bow until the post-war Nelsons.

After a chase that lasted only a few minutes—and almost involved a collision between Dreadnought and Temeraire—the former rammed U-29 and cut the submarine in half. U-29 sank almost immediately, taking all hands. The sinking of U-29 was the only consequential operation of war ever conducted by HMS Dreadnought. She missed the Battle of Jutland due to a refit. In reserve by the end of the war, she never fired her guns against a surface target and was scrapped soon after the conclusion of the peace.

The crew of HMS Dreadnought received several congratulatory telegrams after the sinking of the sub. One of these read “Bunga Bunga!” in reference to the “Dreadnought Hoax” of 1910. A handful of literary pranksters (including Virginia Woolf) associated with the Bloomsbury Group donned blackface and what they imagined to be royal Abyssinian costume and convinced the Royal Navy to grant them a tour of the HMS Dreadnought. While on the tour, the group would yell “Bunga Bunga!” whenever they saw something interesting or surprising. The prank became a minor scandal in the Royal Navy.

Recommended: Imagine a U.S. Air Force That Never Built the B-52 Bomber

Recommended: Russia's Next Big Military Sale - To Mexico?

Recommended: Would China Really Invade Taiwan?

Overall, submarine attacks saw mixed success against warships throughout World War I. The British and French lost several older pre-dreadnought battleships to submarine attack, but of the dreadnoughts, only the French battleship Jean Bart took serious damage from a submarine. In addition, the super-dreadnought HMS Audacious was sunk by a mine laid by a German surface vessel. Even when the Germans attempted to combine surface and submarine operations, they saw little success; efforts to lure the Grand Fleet into submarine ambushes in 1916 and 1918 yielded no sinkings. In 1917, the Germans turned to British commerce with considerably more success, almost starving Britain before the implementation of the convoy system. And in World War II submarines would see enormous success against capital ships, sinking numerous battleships and aircraft carriers.

Robert Farley, a frequent contributor to TNI, is author of The Battleship Book. The views expressed here are his personal views and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Defense, the U.S. Army, the Army War College, or any other department or agency of the U.S. government.

Image: Wikimedia