Can Japan Continue To Grow Into The Military Ally The U.S. Needs?

In recent years, Tokyo has undertaken a major program of military modernization. Will that continue under a new prime minister? Will it be enough considering China's growing military power?

The security environment in the Western Pacific is becoming more challenging for the U.S., its friends and allies. China seeks to dominate the region and project power globally. North Korea is expanding its arsenal of ballistic missiles and nuclear warheads. To successfully deter Beijing and Pyongyang, and counter their ability to use military coercion, the U.S. is improving its defense posture in the region both qualitatively and quantitatively. U.S. allies in the region, chief among them Japan, need to do the same. But will Japan make the appropriate investments?

The balance of powers in the Western Pacific is changing rapidly. China is seeking to build a “great power” military that could outmatch the U.S. It is investing in a wide range of high-tech capabilities. Many of these are designed explicitly to counter areas of U.S. advantage or exploit clear vulnerabilities. In particular, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) is rapidly expanding its capabilities to conduct massed, long-range strikes against both fixed facilities and mobile forces. The PLA Air Force is now operating its own version of a fifth-generation stealth fighter and will soon introduce a new long-range strategic bomber. The PLA has deployed a large number of long-range precision-guided ballistic and cruise missiles, one of which, the DF-21, is believed to be specifically designed to attack large surface warships such as U.S. aircraft carriers. Conventionally-armed missiles will be employed in massed attacks, intended to cripple opposing forces at the outset of hostilities. The PLA Navy is rapidly expanding with new attack submarines, aircraft carriers, missile destroyers and large amphibious warfare ships.

In response, the U.S. military is making significant changes to its force posture and concepts of operation. The overall goal is to distribute units more widely throughout the region, make each formation and platform more lethal and agile, and enable joint force commanders to employ capabilities across all the warfare domains. The Marine Corps’ concept for Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations, which focuses on smaller, agile formations that are constantly moving around in proximity to hostile forces while conducting long-range fires, exemplifies the change in how the U.S. plans to conduct future high-end warfare.

The U.S. military is investing in new and expanded capabilities to support these forces. One of the most important areas for modernization is in long-range, precision strike systems such as the Long-Range Air to Surface Missile, the Tomahawk cruise missile Block V, and the Army’s Precision Strike Missile. Another area is missile defense, using land-based systems such as Aegis Ashore and the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense System, and the sea-based Aegis Ballistic Missile Defense System with the new SPY-6 radar.

U.S. allies share Washington’s view on the growing security threat posed by China. In response, they are increasing defense expenditures and spending more on modernization. A major initiative in this is the acquisition of the F-35 Joint Strike Fighter by Japan, Australia and South Korea.

It is impossible to overestimate the importance of Japan as a U.S. ally. Japan plays a unique role in the security of the Indo-Pacific region due to its location, economic power and close ties to the United States. The U.S. hosts Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps forces in Japan precisely because of its unique geographic position.

The government of Prime Minister Shinzo Abe made deterrence of the Chinese and North Korean threats its number one security priority. To that end it has pursued a national security strategy focused on improving the Japanese Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) both qualitatively and quantitatively, and developing the capability to conduct multi-domain operations.

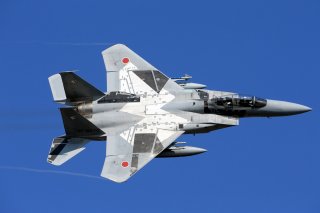

In recent years, Tokyo has undertaken a significant program of military modernization designed not only to improve its ability to defend the homeland and surrounding waters, but also to project military power to more distant regions. In addition to committing to purchase some 147 F-35s, Japan has acquired or plans to buy V-22 tiltrotor transport aircraft, P-8 anti-submarine warfare planes, KC-46A aerial refueling tankers, AH-64 Apache gunships and Patriot air defense systems from the U.S. Most of the country’s fleet of F-15Js will be upgraded with new electronics and the ability to carry advanced weapons.

In addition, Japan is investing in indigenously-produced capabilities. The JSDF has modified two Izumi class destroyers into mini-aircraft carriers capable of handling the short-takeoff/vertical landing F-35B. The country has begun an R&D program for a sixth-generation fighter to replace its aging F-1s. Japan also will collaborate with the United States on developing and deploying an array of small, low-orbiting missile warning satellites.

One area that has become problematic is missile defense of the homeland. Several years ago, the Abe government decided to acquire two Aegis Ashore missile defense systems. This is the same system currently deployed in Europe. However, the Japanese Ministry of Defense announced it was halting the procurement. Given the growing threat posed by China’s and North Korea’s expanding arsenals of ballistic missiles, many of which are nuclear-capable, Japan needs to make a serious commitment to a national missile defense capability.

The end of the Abe era is a time to consider Japan’s future role in the security architecture of the Indo-Pacific region. Frankly, Japan needs to do more if it is to have any hope of deterring China and North Korea. It must build on the efforts of the past decade. In essence, Japan needs to be able to deflect and degrade any initial Chinese or North Korean attack, providing time for the U.S. and other allies to respond militarily. With the proper additional investments in offensive and defensive capabilities, it could be an "unsinkable aircraft carrier," the role played by Great Britain during much of World War II.

This means, in part, investing seriously in active and passive defenses to counter the air and missile threats from China and North Korea. But it also means being able to conduct long-range strikes for the purpose of disrupting enemy operations. Some observers have gone even farther, proposing Japan adopt a strategy of “active denial” designed to make Japan less vulnerable to attack by expanding both its defensive capabilities and simultaneously increasing its capability to attrit hostile offensive forces even at long distances from the Home Islands.

Dan Gouré, Ph.D., is a vice president at the public-policy research think tank Lexington Institute. Goure has a background in the public sector and U.S. federal government, most recently serving as a member of the 2001 Department of Defense Transition Team. You can follow him on Twitter at @dgoure and the Lexington Institute @LexNextDC. Read his full bio here.