Game Changer: The Navy Wants to Rearm Warships with Missiles at Sea

The U.S. Navy's Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, equipped with advanced missile systems like the Mk 41 vertical launch system (VLS), face a significant logistical challenge in prolonged conflicts due to their inability to rearm at sea.

Summary: The U.S. Navy's Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, equipped with advanced missile systems like the Mk 41 vertical launch system (VLS), face a significant logistical challenge in prolonged conflicts due to their inability to rearm at sea. Unlike previous naval vessels, these modern warships require port visits to reload their long-range missiles, a process that could take weeks and diminish their combat readiness. This reliance on port facilities exposes a strategic vulnerability, especially in the Pacific where the demand for missile cells could exceed 10,800 per month in intense conflicts. Efforts are underway to develop new technologies and methods for at-sea rearming, with initiatives like the Transferrable Re-Arming Mechanism (TRAM) promising to revolutionize naval logistics by allowing ships to reload without returning to port, potentially increasing combat persistence and reducing operational downtime.

Challenges and Innovations in Rearming U.S. Navy's Guided-Missile Destroyers at Sea

The U.S. Navy’s workhorse warships, Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyers, can sail into the fight with enough long-range munitions onboard to reshape entire battlespaces. But despite the incredible punch these vessels can pack, America would struggle to keep them armed throughout a prolonged conflict as each vessel would be forced to return to friendly ports for rearming.

Unlike in years past, where even the massive 16-inch Mark 7 naval guns of America’s Iowa-class battleships could be replenished by supply ships while underway, America’s modern warships heavily rely on longer-ranged missiles that cannot currently be replenished at sea. So, while these vessels can now engage a much wider variety of targets from significantly longer distances, each vessel must leave the battlespace and sail back to a friendly port to be re-armed before re-entering the fight – a process that could take weeks.

“Assuming the battle goes on longer than a single missile load, you need to rotate shooters out to reload and return to the scene of battle,” said James Holmes, a former surface warfare officer and the J. C. Wylie chair of maritime strategy at the Naval War College.

And this problem is larger than you might think. A 2019 study conducted by the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, estimates that the U.S. Navy Pacific fleet would likely expend 360 vertical launch system cells per day, or more than 10,800 per month if a large-scale fight were to break out in the Pacific – or at least, they would if they could be re-armed rapidly enough to sustain combat operations. This means that U.S. warships would have to make multiple trips to rearm.

This is akin to deploying to the fight with only a single magazine and having to fly back to the U.S. to reload every time your rifle ran dry. It may not be a serious problem during peacetime, but in the event of large-scale war, it becomes a massive strategic vulnerability. But it’s a vulnerability the Navy has a plan to solve sooner, rather than later.

THE VLS REVOLUTION

The Navy’s modern underdeck missile modules provide a significant leap in combat capability over previous deck-borne weapon systems, combining 360° hemispherical firepower (the ability to fire in any direction) with a wide array of weapons housed in standard modular containers. As a result, ships can be equipped with different combinations of weapons depending on the mission, and even more importantly, can be equipped with new weapons as they emerge without the need for significant refits.

The centerpiece of the U.S. Navy’s long-range fires and air-defense capabilities comes in the form of the Lockheed Martin-sourced Mk 41 vertical launch system (VLS), made up of one or more eight-cell modules that can be installed in 13 different potential configurations in warships of varying sizes to provide anywhere from a single module with eight weapon cells to a combination of 16 modules for a total of 122 cells.

These modules come in two different sizes. The taller 25-foot “strike module” is capable of accommodating all of the missiles that modern U.S. Navy warships leverage, while the slightly smaller 22-foot “tactical” modules can carry nearly all VLS-launched weapons, with the notable exceptions of the larger long-range land-attack Tomahawk cruise missiles and ballistic missile interceptors.

Each VLS cell houses a single watertight canister that can accommodate surface-to-air, anti-ship, anti-submarine, and land attack missiles, with most weapons housed one per cell, but some smaller weapons – like the RIM-162 Evolved SeaSparrow Missile – loaded four to a single cell.

Thanks to these systems, a single Ticonderao-class cruiser or Arleigh Burke-class destroyer can fill a wide variety of combat and peacekeeping roles depending on the types and mix of weapons carried onboard.

Those cells are filled in friendly ports around the world, using a combination of these (and potentially other) weapons:

- RIM-66 SM-2 Standard Missile: Medium-range surface-to-air missile (SAM) for air defense;

- RIM-156A SM-2 Block IV: Extended-range surface-to-air missile interceptor modified for terminal phase ballistic missile defense;

- RIM-174 SM-6 Standard Missile: Extended-range SAM that can also be used for anti-ship and terminal ballistic missile defense roles;

- RIM-161 SM-3: Ballistic missile defense interceptor for engaging short- to intermediate-range ballistic missiles;

- RIM-162 Evolved SeaSparrow Missile (ESSM): Short to medium-range SAM designed to counter supersonic maneuvering anti-ship missiles;

- BGM-109 Tomahawk: Long-range, all-weather, subsonic cruise missile capable of land-attack missions;

- RUM-139 VL-ASROC (Vertical Launch Anti-Submarine Rocket): Anti-submarine weapon that deploys a lightweight torpedo for submarine engagements.

The first vessels equipped with these vertical launch systems were Ticonderoga-class guided missile cruisers, starting with the USS Bunker Hill in 1986. These larger surface combatants were designed to support command-and-control operations as carrier strike-group flagships, while also accommodating eight VLS modules in both forward and aft compartments, each of which house 61 individual cells for a total of 122.

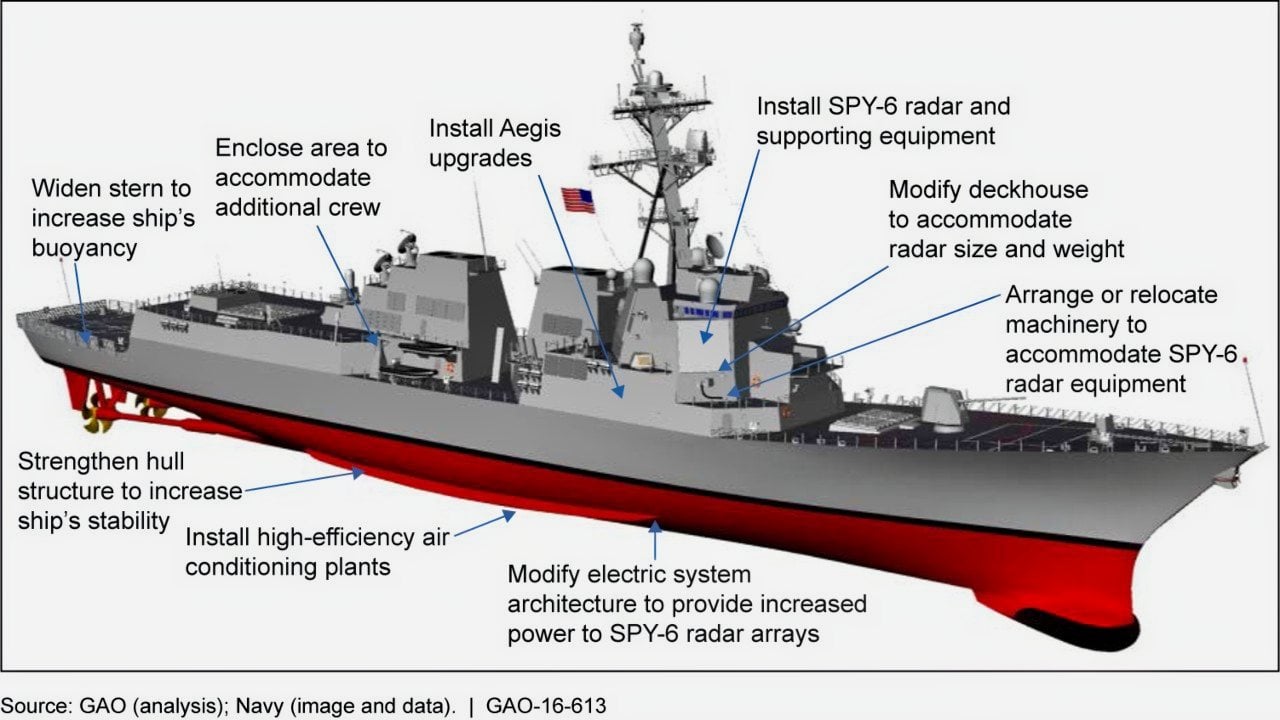

The system proved so useful that it became the centerpiece weapon platform of the new Arleigh Burke-class destroyers that followed, with early Flight 1 and 2 Burkes equipped with forward 29-cell and aft 61-cell systems for a total of 90, and later Flight IIA and III Burkes increasing the forward module to 32-cells and the rear to 64, for a total of 96.

The hardware and software associated with these systems have seen consistent updates and upgrades since initial fielding, but not all of the changes have increased its capability. Earlier Mk 41 VLS designs included a collapsable “strike-down crane” that would allow the crew onboard the vessel to remove spent canisters and replace them with new ones, making it possible to rearm a VLS-equipped warship at sea. However, this system proved not only difficult to work with at sea, but utterly unable to manage larger munitions like Tomahawk cruise missiles and ballistic missile interceptors, prompting the Navy to remove them both from the design of future warships, as well as from ships that already carried them.

As a result, despite the incredible capability provided by the Mk 41 system, both cruisers and destroyers effectively became single-magazine weapon platforms – capable of carrying out missions using the variety of munitions onboard, but forced to return to properly equipped homeports to be rearmed.

This hasn’t been a significant point of concern in recent asymmetric conflicts, which have seen extensive use of sea-launched Tomahawk cruise missiles as America’s preferred form of kinetic diplomacy. As vessels expend their onboard complement of missiles, they can simply rotate out to be rearmed. However, in the significantly higher operational tempo of a near-peer conflict with a large and well-equipped Navy like China’s PLA-N, this could quickly become a significant strategic vulnerability.

THE REARMING PROBLEM

The United States Navy has been resupplying warships at sea since the end of the 19th century, with vessels receiving coal deliveries while underway to limit the predictability of their port stops. Today, that effort has expanded into the Navy’s Military Sealift Command, which boasts a fleet of some 130 vessels and includes ships that specialize in delivering fuel along with just about anything (and everything) else an operating vessel may need to stay in the fight – besides the missiles in question.

“Future conflicts will require the Navy to reload quickly. Surface combatants and submarines engaged in high-end combat could expend their missiles in a matter of days – possibly even hours,” explained retired U.S. Navy Lieutenant Commander Tom Granger in an op-ed he penned for Proceedings in 2018. Granger, who served 30 years in the Navy, was a member of the Navy Munitions Command’s working group focused on rapid-reload concepts for Tomahawk cruise missiles.

Currently, America’s Pacific fleet can only rearm its warships at specific ports in Japan, Guam, Hawaii, and California.

“These reload limitations allow a potential adversary the convenience of only having to target a limited number of port facilities to eliminate the U.S. Navy’s missile rearming capabilities in any theater of conflict,” Granger wrote. If ports in Japan and Guam are destroyed or otherwise contested, ships would have to sail two weeks or more to reach Hawaii, or more than three weeks to reach California – and then sail the same distance back to rejoin the fight.

This isn’t a vulnerability the Navy has resigned itself to, however. In February of 2023, Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) Carlos Del Toro reaffirmed the force’s ongoing efforts to rearm surface combatants without the need for a lengthy retreat from the fight.