Game Changer: The Navy Wants to Rearm Warships with Missiles at Sea

The U.S. Navy's Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, equipped with advanced missile systems like the Mk 41 vertical launch system (VLS), face a significant logistical challenge in prolonged conflicts due to their inability to rearm at sea.

Summary: The U.S. Navy's Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, equipped with advanced missile systems like the Mk 41 vertical launch system (VLS), face a significant logistical challenge in prolonged conflicts due to their inability to rearm at sea. Unlike previous naval vessels, these modern warships require port visits to reload their long-range missiles, a process that could take weeks and diminish their combat readiness. This reliance on port facilities exposes a strategic vulnerability, especially in the Pacific where the demand for missile cells could exceed 10,800 per month in intense conflicts. Efforts are underway to develop new technologies and methods for at-sea rearming, with initiatives like the Transferrable Re-Arming Mechanism (TRAM) promising to revolutionize naval logistics by allowing ships to reload without returning to port, potentially increasing combat persistence and reducing operational downtime.

Challenges and Innovations in Rearming U.S. Navy's Guided-Missile Destroyers at Sea

The U.S. Navy’s workhorse warships, Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyers, can sail into the fight with enough long-range munitions onboard to reshape entire battlespaces. But despite the incredible punch these vessels can pack, America would struggle to keep them armed throughout a prolonged conflict as each vessel would be forced to return to friendly ports for rearming.

Unlike in years past, where even the massive 16-inch Mark 7 naval guns of America’s Iowa-class battleships could be replenished by supply ships while underway, America’s modern warships heavily rely on longer-ranged missiles that cannot currently be replenished at sea. So, while these vessels can now engage a much wider variety of targets from significantly longer distances, each vessel must leave the battlespace and sail back to a friendly port to be re-armed before re-entering the fight – a process that could take weeks.

“Assuming the battle goes on longer than a single missile load, you need to rotate shooters out to reload and return to the scene of battle,” said James Holmes, a former surface warfare officer and the J. C. Wylie chair of maritime strategy at the Naval War College.

And this problem is larger than you might think. A 2019 study conducted by the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments, estimates that the U.S. Navy Pacific fleet would likely expend 360 vertical launch system cells per day, or more than 10,800 per month if a large-scale fight were to break out in the Pacific – or at least, they would if they could be re-armed rapidly enough to sustain combat operations. This means that U.S. warships would have to make multiple trips to rearm.

This is akin to deploying to the fight with only a single magazine and having to fly back to the U.S. to reload every time your rifle ran dry. It may not be a serious problem during peacetime, but in the event of large-scale war, it becomes a massive strategic vulnerability. But it’s a vulnerability the Navy has a plan to solve sooner, rather than later.

THE VLS REVOLUTION

The Navy’s modern underdeck missile modules provide a significant leap in combat capability over previous deck-borne weapon systems, combining 360° hemispherical firepower (the ability to fire in any direction) with a wide array of weapons housed in standard modular containers. As a result, ships can be equipped with different combinations of weapons depending on the mission, and even more importantly, can be equipped with new weapons as they emerge without the need for significant refits.

The centerpiece of the U.S. Navy’s long-range fires and air-defense capabilities comes in the form of the Lockheed Martin-sourced Mk 41 vertical launch system (VLS), made up of one or more eight-cell modules that can be installed in 13 different potential configurations in warships of varying sizes to provide anywhere from a single module with eight weapon cells to a combination of 16 modules for a total of 122 cells.

These modules come in two different sizes. The taller 25-foot “strike module” is capable of accommodating all of the missiles that modern U.S. Navy warships leverage, while the slightly smaller 22-foot “tactical” modules can carry nearly all VLS-launched weapons, with the notable exceptions of the larger long-range land-attack Tomahawk cruise missiles and ballistic missile interceptors.

Each VLS cell houses a single watertight canister that can accommodate surface-to-air, anti-ship, anti-submarine, and land attack missiles, with most weapons housed one per cell, but some smaller weapons – like the RIM-162 Evolved SeaSparrow Missile – loaded four to a single cell.

Thanks to these systems, a single Ticonderao-class cruiser or Arleigh Burke-class destroyer can fill a wide variety of combat and peacekeeping roles depending on the types and mix of weapons carried onboard.

Those cells are filled in friendly ports around the world, using a combination of these (and potentially other) weapons:

- RIM-66 SM-2 Standard Missile: Medium-range surface-to-air missile (SAM) for air defense;

- RIM-156A SM-2 Block IV: Extended-range surface-to-air missile interceptor modified for terminal phase ballistic missile defense;

- RIM-174 SM-6 Standard Missile: Extended-range SAM that can also be used for anti-ship and terminal ballistic missile defense roles;

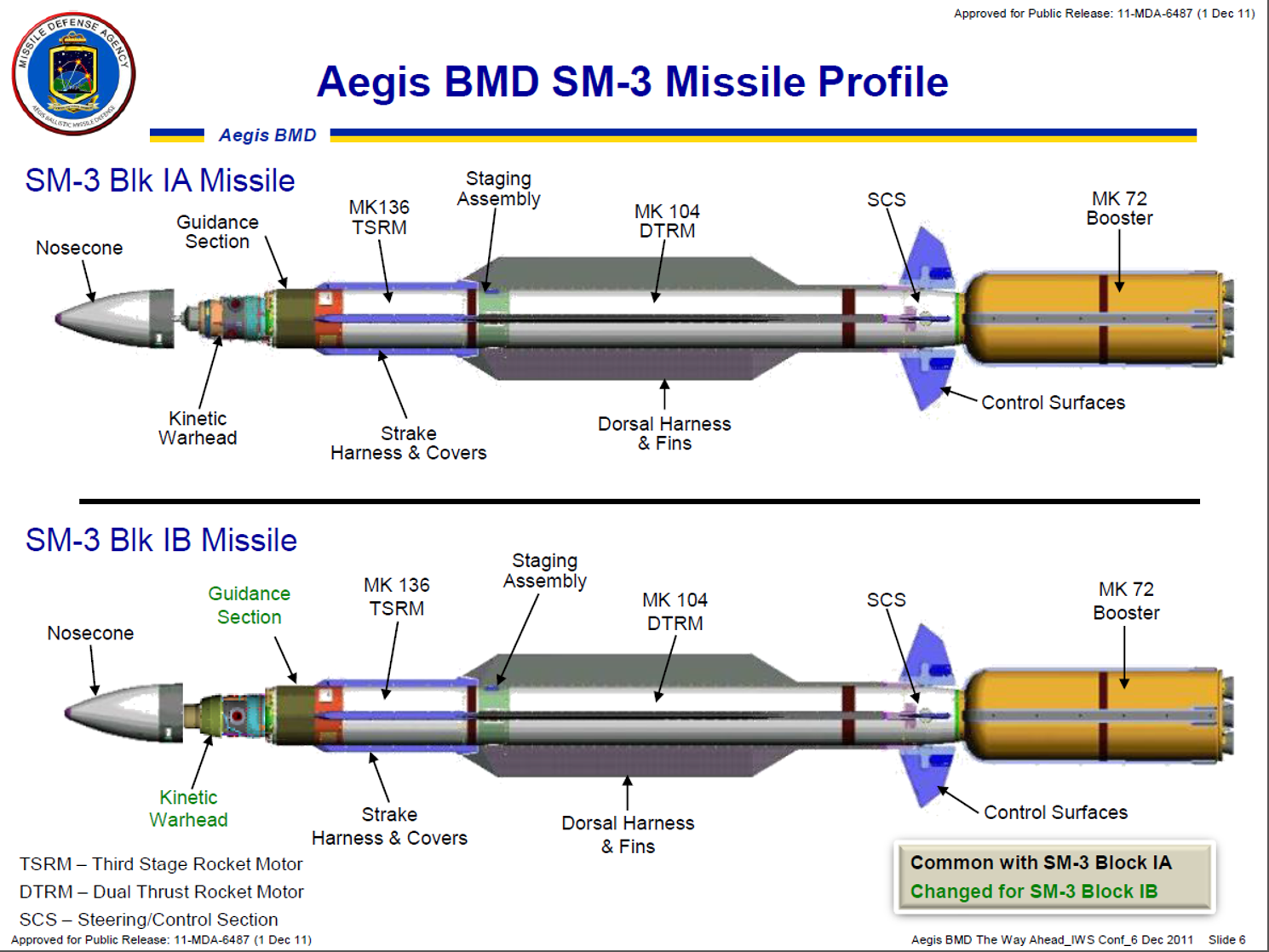

- RIM-161 SM-3: Ballistic missile defense interceptor for engaging short- to intermediate-range ballistic missiles;

- RIM-162 Evolved SeaSparrow Missile (ESSM): Short to medium-range SAM designed to counter supersonic maneuvering anti-ship missiles;

- BGM-109 Tomahawk: Long-range, all-weather, subsonic cruise missile capable of land-attack missions;

- RUM-139 VL-ASROC (Vertical Launch Anti-Submarine Rocket): Anti-submarine weapon that deploys a lightweight torpedo for submarine engagements.

The first vessels equipped with these vertical launch systems were Ticonderoga-class guided missile cruisers, starting with the USS Bunker Hill in 1986. These larger surface combatants were designed to support command-and-control operations as carrier strike-group flagships, while also accommodating eight VLS modules in both forward and aft compartments, each of which house 61 individual cells for a total of 122.

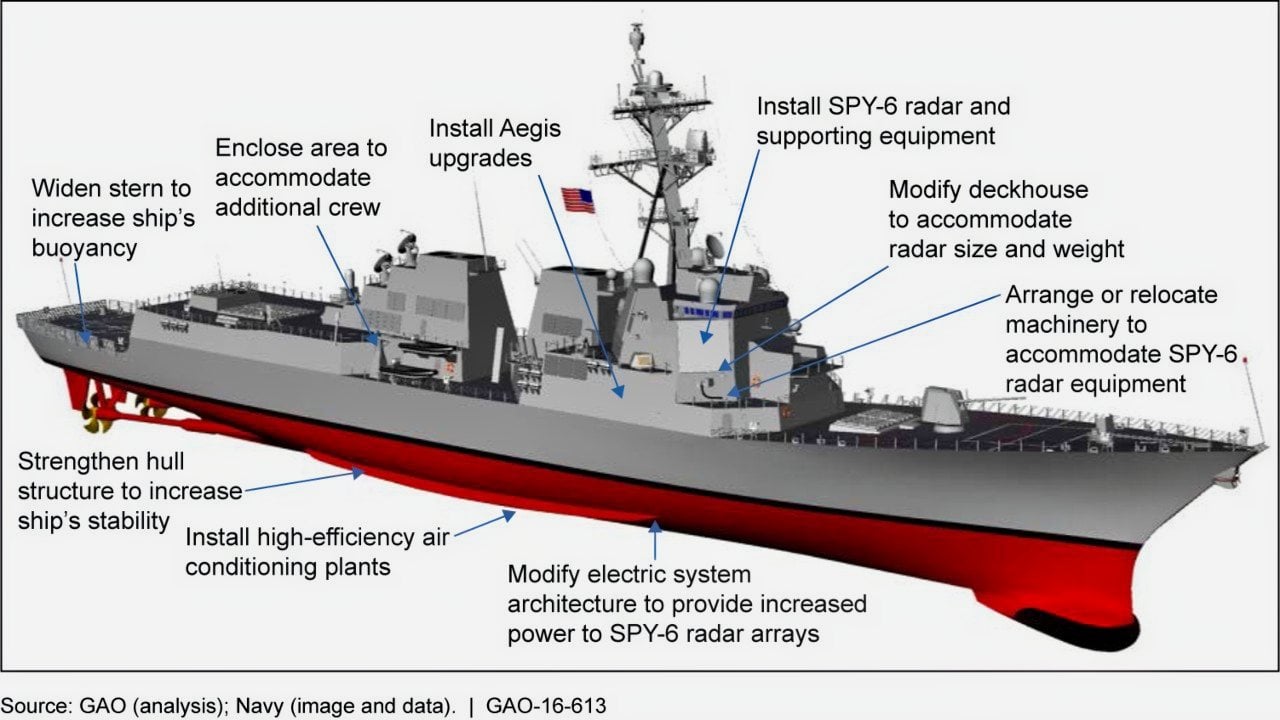

The system proved so useful that it became the centerpiece weapon platform of the new Arleigh Burke-class destroyers that followed, with early Flight 1 and 2 Burkes equipped with forward 29-cell and aft 61-cell systems for a total of 90, and later Flight IIA and III Burkes increasing the forward module to 32-cells and the rear to 64, for a total of 96.

The hardware and software associated with these systems have seen consistent updates and upgrades since initial fielding, but not all of the changes have increased its capability. Earlier Mk 41 VLS designs included a collapsable “strike-down crane” that would allow the crew onboard the vessel to remove spent canisters and replace them with new ones, making it possible to rearm a VLS-equipped warship at sea. However, this system proved not only difficult to work with at sea, but utterly unable to manage larger munitions like Tomahawk cruise missiles and ballistic missile interceptors, prompting the Navy to remove them both from the design of future warships, as well as from ships that already carried them.

As a result, despite the incredible capability provided by the Mk 41 system, both cruisers and destroyers effectively became single-magazine weapon platforms – capable of carrying out missions using the variety of munitions onboard, but forced to return to properly equipped homeports to be rearmed.

This hasn’t been a significant point of concern in recent asymmetric conflicts, which have seen extensive use of sea-launched Tomahawk cruise missiles as America’s preferred form of kinetic diplomacy. As vessels expend their onboard complement of missiles, they can simply rotate out to be rearmed. However, in the significantly higher operational tempo of a near-peer conflict with a large and well-equipped Navy like China’s PLA-N, this could quickly become a significant strategic vulnerability.

THE REARMING PROBLEM

The United States Navy has been resupplying warships at sea since the end of the 19th century, with vessels receiving coal deliveries while underway to limit the predictability of their port stops. Today, that effort has expanded into the Navy’s Military Sealift Command, which boasts a fleet of some 130 vessels and includes ships that specialize in delivering fuel along with just about anything (and everything) else an operating vessel may need to stay in the fight – besides the missiles in question.

“Future conflicts will require the Navy to reload quickly. Surface combatants and submarines engaged in high-end combat could expend their missiles in a matter of days – possibly even hours,” explained retired U.S. Navy Lieutenant Commander Tom Granger in an op-ed he penned for Proceedings in 2018. Granger, who served 30 years in the Navy, was a member of the Navy Munitions Command’s working group focused on rapid-reload concepts for Tomahawk cruise missiles.

Currently, America’s Pacific fleet can only rearm its warships at specific ports in Japan, Guam, Hawaii, and California.

“These reload limitations allow a potential adversary the convenience of only having to target a limited number of port facilities to eliminate the U.S. Navy’s missile rearming capabilities in any theater of conflict,” Granger wrote. If ports in Japan and Guam are destroyed or otherwise contested, ships would have to sail two weeks or more to reach Hawaii, or more than three weeks to reach California – and then sail the same distance back to rejoin the fight.

This isn’t a vulnerability the Navy has resigned itself to, however. In February of 2023, Secretary of the Navy (SECNAV) Carlos Del Toro reaffirmed the force’s ongoing efforts to rearm surface combatants without the need for a lengthy retreat from the fight.

“Winning will require [keeping] our assets in the fight. Rearming our warships’ vertical launch tubes at sea is amongst the clearest example of sustaining capacity and increased persistent combat power from the current force,” Del Toro said. But as simple as replenishing launch cells at sea may seem in theory, in practice, it comes with significant engineering hurdles… and even more risk.

Replacing spent VLS cells on a pier is delicate work in itself. Hoisting a 3,000-pound 25+ foot canister from a horizontal position to a vertical one, positioning it properly over a hole designed to accommodate the exact size of the cell with practically no additional tolerances, and lowering it into position is challenging enough before you consider the fact that the canisters house a combination of rocket fuel and high-explosive warheads. Reloading these systems can take as long as two or even three full days. This process becomes exponentially more dangerous when being done across ships tethered together while underway at sea and during a fight.

This forces military planners to find a way to maintain sufficient fighting capacity in theater while constantly rotating ships into and out of the battlespace, but also paints a significant target on the friendly ports equipped for the job.

BABY STEPS TOWARD AT-SEA REARMING

The first step toward solving the rearming problem is to equip vessels for the job, but not with the intent of underway replenishment. Instead, these properly equipped vessels can turn any friendly port into a rearming station. The premise is to tie the resupply ship to a stationary pier, allowing the cruiser or destroyer to pull up alongside it and be secured in place with bumpers between the vessels. From there, the delicate work of lifting and then lowering VLS cells into their respective modules can be done.

This approach was demonstrated aboard the USS Spruance (DDG 111) destroyer in September 2022, using an offshore support vessel contracted to the Navy’s Military Sealift Command, called the Ocean Valor. Yet, a subsequent effort conducted while anchored in a calm harbor a month later failed.

The Ocean Valor was equipped with a dynamic positioning system that controls ship speed and steering to keep it properly positioned approximately 90 feet from the destroyer and at the right angle. According to Capt. Kendall Bridgewater, commodore of Military Sealift Command Pacific, the system functioned so well that he doesn’t believe keeping bumpers in place, meant to protect the ships in the event of a collision, would even be necessary moving forward.

However, despite the two ships holding the proper positions, the rocking sea and wind made the missile canisters (which were inert for the test) sway in a way that was unsafe for the destroyer’s personnel to approach and guide into the launch module.

This program proved that the Navy can rearm ships in more ports than ever, but still serves as only the initial step toward resolving this lasting vulnerability. In the long term, the Navy intends to be able to rearm VLS cells while warships and resupply ships are sailing side by side at speeds of around 12 knots (a bit shy of 14 miles per hour), just as they do for standard resupply operations. This not only creates challenges regarding ship positioning, but prevents ships from breaking away from one another rapidly in the event and an inbound attack. Both are challenges engineers within the Office of Naval Research continue to contend with.

To that end, multiple new crane systems, more specialized than the one used aboard the Ocean Valor, are already in active development. Further, another successful demonstration of a similar pier-side rearming capability using a different type of crane, this time with the USS Porter tied “skin-to-skin” to the USNS William McLean dry cargo ship, was announced in August 2023.

Another possibility is devising a system that transfers these missile cells to ships using a similar pulley system to the ones leveraged for equipment and supply transfers today. However, it would mean that the warship itself would need the right equipment to transition the canisters from a horizontal to a vertical position, as well as a strong enough crane to then move the canisters into their modules. But another approach now appears even more promising.

In 2024, the Navy is expected to conduct an at-sea demonstration of the new Transferrable Re-Arming Mechanism (TRAM) developed by the Naval Surface Warfare Center Port Hueneme Division using a 1996 proposal penned by former Army warrant officer turned Marine engineer, Marvin Miller as its basis. This design, which includes the use of an articulating crane that can lift and rotate canisters into the proper vertical position was considered technologically unfeasible in the mid-1990s, but the Navy seems confident it can make it work today.

If the Navy’s new approach to Miller’s concept works as he envisioned, underway rearming of VLS cells should be possible in sea states ranging from a zero on the Beaufort Scale (zero wind speed, zero wave height) all the way to a five (with 17-21 knot wind speeds and waves maxing out at six-eight feet tall).

According to reporting from NavalNews, Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Admiral Lisa Franchetti observed a TRAM demonstration at Port Hueneme in December 2023, and expressed her approval of the program’s progress and capabilities, though to date, publicly available information remains somewhat sparse.

The at-sea demonstration of this new system is anticipated sometime in the summer of 2024, but to date, no further details have been released.

HUGE IMPLICATIONS

The long-term implications of rearming surface combatants at sea are difficult to overstate: according to the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments analysis, as few as just two or three resupply ships that could rearm forward deployed destroyers would have the same impact as fielding a whopping 18 additional cruisers and destroyers in theater, simply by eliminating the need for lengthy trips back and forth from friendly ports.

“Viewed in this light, a fleet VLS rearming at sea capability could provide a ‘value’ in equivalent combatants of at least $11-37 billion, and would be a high-return investment for the Navy,” Tim Walton, a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute’s Center for Defense Concepts and Technology and one of the co-authors of the study later told Defense News.

But in the minds of military planners, it’s not the cost savings that really matter, but rather the increased combat capacity.

“This capability will herald nothing short of a revolution in naval surface warfare logistics,” Del Toro said. The at-sea re-arming option provided by TRAM is “a game-changing [capability] that will be operational within two to three years, and will make our surface navy more formidable, serving as a powerful maritime deterrent,” he said.

While a great deal of our focus on defense technology tends to center around emerging technologies and capabilities that could have entirely new battlefield effects, the effort to find a way to rearm the U.S. Navy’s warships at sea serves as an important reminder that deterring large-scale conflict with nation-level adversaries has never been strictly about new technologies.

In reality, the most effective technology-based programs are often focused not on fielding new systems or platforms, but rather, on increasing the effectiveness or efficiency of existing weapon systems. Fielding entirely new warships that are purpose-built to be rearmed underway, alongside entirely new fleets of resupply vessels designed with that distinct purpose would surely be the most effective solution to the Navy’s rearmament problem, but such a solution is impractical from both budgetary and timeline perspectives.

Fielding a relatively low-cost method of rearming the Navy’s existing warships, using existing resupply vessels, may not be as sexy, but it can be done faster and for a lot less money, while delivering the same effect.

And when it comes to deterring or, at worst, winning a large-scale conflict, that’s the sort of technological breakthrough that truly matters most.

About the Author: Alex Hollings

Alex Hollings is the editor of the Sandboxx blog and a former U.S. Marine that writes about defense policy and technology. He lives with his wife and daughter in Georgia. This first appeared on Sandboxx.