How America Is Finally Strengthening Its Manufacturing Supply Chain

It has taken decades for the “hollowing out” of American manufacturing to be recognized as a serious national security issue.

On February 24, President Joe Biden signed an executive order designed to protect the future of America’s manufacturing supply chains. Building on a previous executive order (“Ensuring the Future is Made in All of America by All of America’s Workers”) signed by the president on January 25, 2021, the “America’s Supply Chain” executive order rests on a policy that the United States “needs resilient, diverse, and secure supply chains to ensure our economic prosperity and national security.” Specifically, these “resilient” supply chains “will revitalize and rebuild domestic manufacturing capacity, maintain America’s competitive edge in research and development, and create well-paying jobs.”

In his supply chain executive order, the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs (APNSA) and the Assistant to the President for Economic Policy (APEP) are jointly tasked with coordinating executive branch actions, which initially includes a one-hundred-day supply chain review. This review includes reports and policy recommendations covering semiconductor manufacturing and advanced packaging supply chains (Commerce Department); high-capacity batteries, including electric batteries (Energy Department); critical minerals, including rare earth elements (Defense Department); and pharmaceuticals and active pharmaceutical ingredients (Health and Human Services Department). The APNSA and APEP will jointly submit the final reports to the president in an unclassified format but may include a classified annex.

In the longer term, and within one year, the APSNA and APEP will submit sectoral supply chain assessments for the defense industrial base (Defense Department); public health and biological preparedness (Health and Human Services); information and communications technology (Commerce and Homeland Security Departments); transportation industrial base (Transportation Department); energy sector (Energy Department); and agricultural commodities and food products (Agriculture Department). In consultation with departmental leaders, the APNSA and APEP will recommend adjustments in the scope of each industrial base assessment, including digital networks, services, assets, and data (“digital products”) and goods, services, and materials that are relevant across defined industrial sectors. They will also add new assessments for goods and materials not included in the above industrial base assessments. The sectoral supply chain assessments will also include a review of the resilience and capacity of U.S. manufacturing supply chains and the industrial and agricultural base (civilian and military) to support national economic security and emergency preparedness.

This executive order has bipartisan support in Congress—and the Covid-19 pandemic has brought the precarious national security situation that America is confronted with in the biopharmaceutical manufacturing sector. “Should Beijing opt to use U.S. dependence on China as an economic weapon and cut supplies of critical drugs, it would have a serious effect on the health of U.S. consumers,” the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission reported in November 2019. Further, on March 17, 2020, The Pharma Letter, an online news site covering the pharmaceutical and biotech industries, reported that Chinese manufacturers accounted for “95% of U.S. imports of ibuprofen, 91% of U.S. imports of hydrocortisone, 70% of U.S. imports of acetaminophen, 40% to 45% of U.S. imports of penicillin and 40% of U.S. imports of heparin, according to Commerce Department data. In all, 80% of the U.S. supply of antibiotics are made in China.”

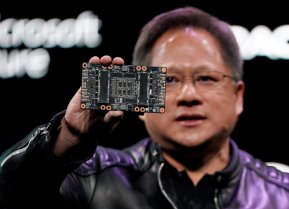

Likewise, in the semiconductor manufacturing sector, China’s government views semiconductor technology as an essential industry, and is spending over $100 billion annually to become self-sufficient in manufacturing as a key component of its Made in China 2025 national industrial policy. China currently manufactures 15 percent of its current industrial needs, but utilizes 60 percent of the worldwide production of semiconductors. In September 2020, the Semiconductor Industry Association and the Boston Consulting Group released a study that strongly recommends federal incentives ($50 billion) to reverse a decades-long trend of declining chip manufacturing in the United States (only 12 percent of existing global chip manufacturing is now produced domestically) and create as many as nineteen major semiconductor manufacturing facilities. This plan, which would produce a 27 percent increase over the current number of domestic commercial fabricators, would create 70,000 new industry jobs over the next ten years. Ford is presently dealing with a shortage of semiconductor chips which is now negatively impacting the company’s automotive production in the United States.

“We need to bring large-scale battery production to the U.S.,” Ford CEO Jim Farley said at a financial conference this past February where he called on the U.S. government to support battery production and the development of electric vehicle charging infrastructure. Global demand for lithium-ion batteries has increased from 19 GWh in 2010 to a production of 160 GWh in 2019 (from a capacity of 285 GWh). China is the global leader in lithium-ion battery cell production today, with 93 “gigafactories,” versus only four such battery gigafactories in the United States. If current trends continue, China is projected to have 140 gigafactories by 2030, while Europe will have seventeen and the United States, ten. Doug Campbell, co-founder of battery start-up Solid Power in Louisville, Colo., recommended that the U.S. government should provide tax breaks and other financial support for companies building lithium-ion battery manufacturing plants. “One thing we do great here is innovate,” said Campbell. “But where there is a chasm is when it gets to manufacturing scale. That is where other nations step in and provide some of that capital before a bank is willing to lean in.”

In the last Congress, Senators Todd Young (R-IN) and Chuck Schumer (D-NY), and Congressmen Ro Khanna (D-CA) and Mike Gallagher (R-WI), introduced the Endless Frontier Act to increase American investments in critical technologies. The act, which expired in the last Congress, proposed expanding the National Science Foundation, providing $100 billion for advancing research and development (R&D), and allocating another $10 billion for establishing regional technology hubs nationwide that would launch new technology-based companies, revive American manufacturing, and create new jobs. Recently, Senate Majority Leader Schumer announced that he would begin working on a new, bipartisan legislative proposal that “must achieve three goals: enhance American competitiveness with China by investing in American innovation, American workers and American manufacturing; invest in strategic partners and alliances: NATO, Southeast Asia and India; and expose, curb, and end once and for all China’s predatory practices which have hurt so many American jobs.”

This new “critical technologies” legislation, with funding focusing on 5G telecommunications technology development and biomedical technology, has the potential to be enacted with Republican and Democrat support. Many Republicans are reassessing their orthodox positions against national industrial policy or strategy—especially as it concerns economic and national security threats emanating from China. Moreover, President Biden’s supply chains executive order neatly fits into his proposed “comprehensive manufacturing and innovation strategy.” This proposed national industrial strategy includes both $400 billion in federal spending on “Buy America” purchases of domestic products, materials, and services, and $300 billion in federal spending on basic research and breakthrough technologies, including federal “seed funding” for commercialization of emerging technologies such as electric vehicles, lightweight materials, 5G, and artificial intelligence.

It has taken decades for American manufacturing to be “hollowed out” and much of this recent effort to on-shore manufacturing and supply chains has been recognized in the last few years as a serious national security issue. It will require years of public and private policy efforts to “reset” what should have been recognized as serious national security concerns years ago—but then too many Americans were making money in the short-term, at the expense of the “existential” longer-term threats.

Thomas A. Hemphill is David M. French Distinguished professor of strategy, innovation and public policy in the School of Management, University of Michigan-Flint.

Image: Reuters.