Is Joe Biden Serious about Negotiating with North Korea?

The Biden administration has nominated a special envoy to the North, Sung Kim. However, Korea is only his hobby, or perhaps light after-hours duty. His day job will continue to be ambassador to Indonesia.

The United States has no ambassador to the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea. That reflects Washington’s foolish belief that diplomatic recognition would imply approval. During the Cold War America and the Soviet Union exchanged ambassadors, maintained embassies, and communicated regularly. Yet the closest diplomatic contact between the United States and DPRK is New York City, with North Korea’s United Nations mission.

The Biden administration has nominated a special envoy to the North, Sung Kim. However, Korea is only his hobby, or perhaps light after-hours duty. His day job will continue to be ambassador to Indonesia.

The DPRK may take this as a slight. That should be of little account, but Pyongyang treats symbolism seriously and might view Kim’s status as evidence that Washington is not serious about engagement. The result could be an unpredictable mix of irritated silence and querulous rants, highlighted by disruptive behavior of one sort or another.

Still, Kim’s combination might work if he was serving in, say, Brunei. After all, no one worries much about what goes on there. However, Indonesia is a complex nation with a host of issues. It is the world’s most populous majority Muslim state, host to generally tolerant Sunni Islam but periodically suffering from religious persecution and terrorism. Jakarta also will be an increasingly important regional player in coming years.

So long as the North largely stays sealed within its own borders, Kim might not worry about working overtime. However, his job is, or at least should be, to actively engage Pyongyang nonetheless.

That means pressing Pyongyang to open a dialogue. Discussing possible strategies with South Korea’s Moon government. Talking to Japanese officials about trying to restart talks long stalled by the controversy over the DPRK kidnapping of Japanese citizens. Attempting to move the Chinese and Russian governments to help address the North and proposing steps they might take. As well as building relationships with non-governmental organizations and companies that have worked or would like to operate in North Korea.

On top of that should be dealing with Congress. There currently are nearly 535 wannabe secretaries of state on Capitol Hill who routinely attempt to impose their views, usually hawkish and interventionist, on the reigning administration, irrespective of party. Most often legislators vote to impose sanctions and restrict their removal, demanding full submission of the country targeted, including Russia, Syria, Iran, or North Korea. Unsurprisingly, these governments typically respond like the United States would if similarly confronted, with dismissive contempt, leaving diplomacy little chance.

Thus, the envoy to Pyongyang should be a full-time job.

Moreover, the Biden administration has no time to waste. Aidan Foster-Carter, an honorary senior research fellow in sociology and modern Korea at Leeds University, recently described how inadequate policy continuity in America and South Korea made it more difficult for them to deal with the North.

“Kim Jong Un is now 37. If he too makes it to 82, that gives him another 45 years: All the way to 2066,” Foster-Carter explained. “That seems unimaginably distant—who knows what our world will be like by then? What we do know is that South Korea will in that time elect and dispatch no fewer than eight—eight!—new and different presidents. This increases to nine just a year later, in 2067. In the U.S., there will be a minimum of five new presidents over the same time period, and perhaps several more if incumbents fail to win re-election.”

If Joe Biden allows this year to slip by—we already are at the halfway mark—he will be entering a year focused on the midterm elections, with the presidential race set to begin in 2023. And Biden might not even run again. At that point, his authority would be draining away daily. Moreover, South Korea’s Moon Jae-in is in his final year in office and was a lame duck even before his party lost two major mayoral races to the opposition. Soon the United States won’t have an effective negotiating partner in the South.

And what follows the liberal Moon administration? The ROK right, which celebrates Seoul’s reliance on American military support, takes a more intransigent stance toward the North. A conservative administration would last until 2027, which is when a second-term Biden administration would be less than two years away from leaving office. The likelihood of energetic engagement with Pyongyang then seems low.

This potentially dismal future comes atop a very crowded foreign policy agenda for the Biden administration. The president will soon be headed to Europe for a NATO meeting and a summit with Russian President Vladimir Putin. China appears to top the administration’s informal enemies list and will disproportionately consume administration attention and resources. So far the world has been providing a constantly changing crisis du jour—Belarus’ skyjacking, Israel’s Palestinian explosion, India’s coronavirus tsunami, Alexie Navalny’s arrest, Burma’s coup, the southern border’s onrush. Who knows what will come next?

Yet delay is not to America’s advantage. In the three years since the failed Hanoi summit, Kim has effectively refused to engage. The DPRK even pulled back from the normal diplomatic discourse around the globe. However, it did not halt its military efforts, highlighted by its October military parade.

Indeed, Gen. Mark A. Milley, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, recently warned Congress that the North “continues to enhance its ballistic missile capability and possesses the technical capacity to present a real danger to the U.S. homeland as well as our allies and partners across the Indo-Pacific.”

That is what Kim and his father did during the Obama administration’s era of strategic patience. Indeed, Kim fils accelerated the pace of both nuclear and missile testing, allowing him to boast that North Korea had acquired its desired deterrent. Unfortunately, unless he is convinced to halt or at least slow his efforts, the challenge will grow dramatically.

A recent Rand Corporation/Asan Institute report notes that “we estimate . . . that, by 2027, North Korea could have 200 nuclear weapons and several dozen intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) and hundreds of theater missiles for delivering the nuclear weapons.” That is only six years away and will possibly occur when a reelected Biden is nearing the end of his tenure.

At that point, the nuclear game almost certainly would be over. It is difficult enough to imagine Kim or any successor surrendering perhaps sixty nuclear weapons now. But two hundred? Especially when they would make the DPRK a serious nuclear power. The North would be close behind China and France, about equal to the United Kingdom, and ahead of Pakistan, India, and Israel. Having dramatically crashed the nuclear club, why should Pyongyang give in when it is ahead of countries accepted by America as members?

There would be no direct threat to the United States since Washington’s nuclear deterrent would remain overwhelming. However, getting involved in a conventional war against the North on Seoul’s behalf would invite nuclear retaliation. It is hard to imagine how Washington could maintain the alliance since acting on it could result in a nuclear attack on the American homeland. Which then would raise the question of whether the South needed its own arsenal to deter North Korea.

Ambassador Kim has good experience, having served as ambassador to South Korea and handled North Korean policy late in the Obama administration. However, his time was a bust, coming after the quickly failed Leap Year agreement. Another four years of inaction “is not an option,” as policymakers have grown fond of saying about their pet initiatives.

Despite five months of largely ignoring North Korea, Biden still has time to act. He should demonstrate his seriousness by choosing a full-time envoy for the DPRK.

Sung Kim might prefer to keep the Indonesia portfolio instead since second comings are not always a great success. In any case, Biden needs a diplomat focused on the North, and needs him or her now. Time already is slipping away.

Doug Bandow is a senior fellow at the Cato Institute. A former Special Assistant to President Ronald Reagan, he is author of Tripwire: Korea and U.S. Foreign Policy in a Changed World and co-author of The Korean Conundrum: America’s Troubled Relations with North and South Korea.

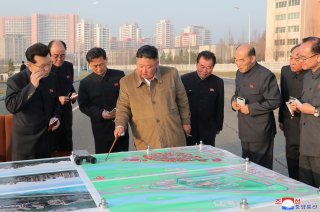

Image: Reuters