SMA Debate: Why Shouldn’t South Korea Pay More for its Defense?

Or even defend itself?

The Cold War is over. South Korea has raced far ahead of the North. Pyongyang cannot expect military support from China or Russia. The United States government is essentially bankrupt. Why shouldn’t South Korea pay more for its defense—or even defend itself?

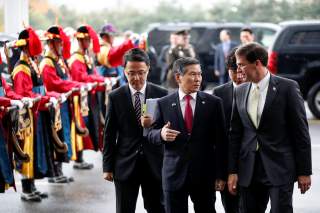

President Donald Trump has reasonably raised the issue with his request for a major increase in contributions from Seoul to underwrite America’s troop presence. After all, South Korea “is a wealthy country and could and should pay more to help offset the cost of defense,” explained Defense Secretary Mark Esper. Alas, he set off wailing and gnashing of teeth across the South. As well as generated predictable complaints from members of America’s foreign policy establishment, whose motto should be “what has been must ever be.” The Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Vipin Narang tartly complained: “Nothing says I love you like a shakedown.”

But the president’s proposal is anything but a shakedown.

Historically, the Korean Peninsula was of no security interest to America. The monarchy was independent but long under Chinese influence. Domestic unrest encouraged the kingdom’s proclamation of the Korean Empire, which freed it from its tributary status toward China. However, Japan defeated both China and Russia in war and became Northeast Asia’s dominant power. In 1905, Tokyo turned the peninsula into a protectorate; five years later, Imperial Japan formally annexed Korea as a colony. Koreans unsuccessfully sought American support, claiming that the 1882 “Treaty of Amity and Commerce” committed Washington to defend their independence; President Teddy Roosevelt declined to intervene.

The peninsula then receded from U.S. consciousness, other than as a target of American missionaries. Some South Koreans, such as Syngman Rhee, later the president of South Korea, went to the United States, where they lobbied for U.S. backing without much effect. It was only the end of World War II and Japan’s surrender which forced U.S. officials to consider the fate of the peninsula. Korea ultimately was divided into American and Soviet occupation zones, which respectively turned into South Korea and North Korea. At that point, the South mostly mattered as a symbol in the Cold War. America’s defense of “its” Korea in June 1950 was seen as necessary to demonstrate America’s commitment to its more important allies, including Japan, still under U.S. occupation, and Western Europe, dependent on the newly created NATO.

And so, the situation remained after the armistice was signed in July 1953. Impoverished, corrupt, war-ravaged, and authoritarian South Korea could not survive without U.S. support. Hence, the “mutual defense” treaty with Washington backed by a military garrison. There was no reason to assume either would be permanent; in fact, President Dwight Eisenhower warned against a long-term U.S. presence in Europe.

By the 1960s the ROK moved ahead of its northern antagonist economically and two decades later Seoul found democracy. Détente with Russia in the 1970s made Soviet support for another North Korean invasion unlikely. China’s Mao Zedong also gained an incentive to avoid a renewed Korean conflict when he warmed relations with America. The disintegration of the Soviet Union left Pyongyang almost entirely dependent on Beijing. Over time the South began to enjoy truly overwhelming advantages: today it has twice the population, fifty-four times the economic strength, a vast technological edge, and is well-integrated globally. Plus, it enjoys the beneficiary of a “mutual” defense treaty with America that is anything but. On the contrary, it is defense welfare, a unilateral commitment to the ROK’s defense. Depending on how one cuts the numbers, the United States has long spent more to protect the South than did an increasingly prosperous South Korea. Such a policy was necessary for 1953. But not in 2019.

Seoul was expected to contribute “host nation support,” as do most countries with American garrisons. Over the last decade, the South paid roughly $800 million annually. In 2018 President Donald Trump requested a jump to about $1.5 billion. Instead of negotiating the typical five-year pact, the two sides agreed to a modest increase, with new negotiations to commence this fall. Washington then proposed a payment of $4.7 billion annually.

South Koreans were not exactly shocked since rumors that such a demand was likely had circulated for months. Nevertheless, South Korean officials can’t imagine contributing anything close to that amount but worry that President Trump might withdraw U.S. troops if they refuse. Secretary Esper observed that Washington was requesting similarly dramatic increases from other U.S. allies, but that did little to quiet concerns in Seoul.

The South’s reluctance to give up its good deal should surprise no one. However, South Koreans are not entitled to a cheap ride at American expense. The principle is simple: serious, mature, developed nations should defend themselves. Unique circumstances might warrant U.S. support for other countries—like the ROK in the aftermath of the Korean War. But when those circumstances pass away, so should American defense subsidies.

South Koreans and their U.S. backers rightly observe that Seoul devotes relatively more to the military than do Europe or Japan. That is true—the threat has always been far greater and under military regimes through the 1980s military outlays also were viewed as contributing to internal security. Nevertheless, without an American presence, South Korea presumably would be spending much more on defense.

Acting like a shield behind which the South could recover after the Korean War was a good policy. However, that era passed long ago and policy should change. South Korea could do far more. And since its defense matters more to South Koreans than Americans, it presumably would do far more if necessary.

The next line of defense offered by some South Koreans as well as U.S. policymakers is that Washington has stationed forces in the peninsula for America’s benefit. In 1950, the Truman administration believed that it was in America’s interest to defend the South, though the most obvious beneficiaries were the South Koreans, who avoided becoming unwilling subjects of North Korea’s Kim Il-sung.

Although for humanitarian reasons, if nothing else, Americans would prefer South Korea to be secure. Today, the latter matters far less geopolitically for the United States. There is no Cold War. Japan long ago recovered from World War II and no longer lacks a military; it is no longer vulnerable to coercion or even attack. Europe is no longer rebuilding in the shadow of Joseph Stalin’s Soviet Union, desperately reliant on America and worried about U.S. credibility. Most importantly, the South can defend itself with abundant human and financial resources at its disposal. There is no need for Washington to garrison the peninsula to protect it even in America’s interest.

Finally, those who insist on continuing U.S. involvement contend that the troops serve dual or multi-purposes: defending the South and containing China. Some expand the second category to include maintaining regional stability, discouraging a regional arms race, and/or meeting other regional contingencies. The latter is a bit like the kitchen sink argument, just say whatever comes to mind and hope that someone somewhere is persuaded.

An army division stationed in the ROK will not inhibit the PRC, which almost certainly does not intend to invade the South. Indeed, to the extent that Beijing takes seriously South Korea’s role in an American containment system, China probably is less inclined to help with North Korea. Most important, no South Korean government, irrespective of its ideological predilections, is likely to voluntarily turn itself into a military target by allowing Washington to use its bases for anything other than the South’s direct defense. Doing so also would make Seoul into a permanent enemy of a neighbor with a long memory.

The other objectives are equally dubious, unattainable, or both. Despite claims of imminent disaster, the region does not appear to be on the brink of war. America’s interest is best served by avoiding than incorporating other nations’ internal conflicts and international controversies. An arms race without U.S. participation could be positive: in recent years a number of countries have armed to improve their deterrent power against China’s navy, something Washington should favor. In any case, the Korean Peninsula is largely irrelevant to the most volatile issues involving the People’s Republic of China.

If American forces are to remain in South Korea, then the president is right to want the country to pay more. And the amount collected should be large. The cost of Washington’s guarantee to the South is not just basing costs. It is raising, equipping, and maintaining additional force structure. The more tasks the U.S. military is expected to undertake, the larger it must be. So Seoul should pay more—a lot more—than it is paying today.

Yet treating American service personnel as mercenaries to be hired out, even if the client is not quite as brutally disreputable as the Saudi Royals, is an affront to U.S. values and security. And that is what the president proposes to do. Put members of the armed forces at risk while Uncle Sam collects the extra money earned. That is truly an awful idea.

Washington should stop protecting South Korea. That is, leave responsibility for South Korea’s defense to the South Koreans. Obviously, Washington should not depart precipitously: it should work with Seoul to develop a withdrawal timetable, giving the latter time to adapt. Rather than pay America, the South would spend its money to expand and upgrade its own forces.