Where did the Modern Mercenary Industry Come From?

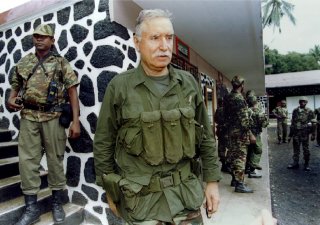

Meet the father of modern mercenary warfare.

Here's What You Need to Know: Frenchman Bob Denard’s bloody antics in the Comoros helped establish a precedent, follow the money.

In the early 1960s, the former Belgian Congo came apart at the seams. U.N.-backed Congolese troops battled the forces of the breakaway region of Katanga, which in turn was supported by hundreds of foreign mercenaries.

Surely no one realized it at the time, but the seeds of a new way of war were planted in the Congo’s rich soil at that time—a way of war cultivated in large part by one man.

Among the pro-Katanga fighters was a tall, handsome, 30-something French soldier-of-fortune named Gilbert Bourgeaud, better known by his nom de guerre “Bob Denard.” The Frenchman was notorious for fearlessly manning a mortar while under heavy attack.

The Congo crisis was the young Denard’s first war-for-hire. He would later take part in conflicts in Yemen, Benin, Gabon, and Angola, among others.

The Katanga rebellion failed and Denard fled. In late 1965, the mercenary reappeared in Congo, this time fighting on the side of strongman Mobutu Sese Seko, a one-time opponent of the Katanga regime.

Following the money, Denard had switched sides.

Mobutu consolidated power and declared himself president in November. Fearful of the mercenaries who had fought against him then for him and who still lingered in “Zaire,” as Mobutu had renamed the country, the new president asked Denard to help disarm one of the more notorious foreign fighters, a Belgian named Jacques Schramme.

Instead, Denard switched sides again. He joined Schramme in trying to overthrow Mobutu.

The coup failed when the mercenaries ran into a platoon of North Korean soldiers accompanying their vice president on a visit to Pyongyang’s African ally. The North Koreans didn’t hesitate to open fire on Denard’s men. Denard was shot in the head and lay paralyzed for two days, as a woman, later to be his first wife, tended his wound with ice and herbs.

Denard’s men then stole a plane and evacuated their wounded boss. Denard walked with a limp for the rest of his life. But the then-37-year-old Frenchman was not done fighting. He returned to Congo for one more (ultimately failed) coup attempt before drifting into other African wars.

Denard’s hasty attack on the leader of Benin in 1977 faltered after just three hours; he left behind live and dead mercenaries, weapons and other gear, and, most damning, documents describing his entire battle plan.

Families of victims of the attack filed suit in France and Benin. In France, Denard was sentenced to five years in prison. In Benin, he was given the death penalty.

But by then Denard was far beyond the reach of either court. He was on a boat, armed to the teeth at the head of a mercenary army, bound for the Indian Ocean island nation of the Comoros in the opening move of what would become a private war lasting nearly 20 years.

Denard’s army in the Comoros would breed an entire generation of mercenaries who, three decades later, would find gainful employment waging war on behalf of a much wealthier client.

The United States.

Mercenary king

A certain class of warrior deliberately obscured their origins, intentions, and methods. They fought not for nation or state, but for money. More often than not, they didn’t even use their real names.

They were mercenaries. In the 1970s and ‘80s, Bob Denard was their king, and the East African island nation of the Comoros was their realm.

The three islands of the Comoros together represent Africa’s third-smallest country, with just 863 square miles of tropical forest-covered mountains and hills, beaches, and dense, seedy, labyrinthine cities for its nearly 800,000 people.

The Comorans are poor people in a poor land. They hunt, they fish, they grow vanilla for export. A quarter of the countries country’s external trade is in the form of old, frequently toxic, decommissioned ships that the desperate Comorans dismantle and recycle or throw away—for a fee.

The islands were French until July 1975. Ahmed Abdallah, then 56 and the founder of his own political party, became the first president of the newly independent nation.

But not for long. In August he was overthrown. And so began one of the most bizarre, and grotesque, political successions in modern history. Abdallah’s overthrower, Said Mohammed Jaffar, was himself overthrown in January 1976 by Denard, acting on behalf of a man named Ali Soilih.

Soilih’s agents had found Denard in Paris, where he was bored and despairing. Africa’s wars of decolonization in the 1960s had been pretty good for the old “dog of war,” as the press liked to call Denard. But several of the Frenchman’s most ambitious gigs had ended in disaster. He found his reputation, and demand for his lethal services, waning.

The future Comoran president’s men offered Denard a $15,000 advance in exchange for his help raising an army against Abdallah. Denard called in some old cronies from Gabon and France, purchased 10 tons of weapons, ammunition, and other supplies; and caught a commercial flight to Moroni, the Comoros’ biggest city.

There Denard equipped some overeager Comoran youths with unloaded weapons and sent them racing across the island in a show of force. There was one fatality: a young relative of Soilih who was decapitated by a machete-wielding guard.

Denard and his mercenaries flew to a neighboring island and laid siege to Abdallah in his villa. The president surrendered. Soilih handed him a passport and a million dollars and made him swear to never re-enter politics. Abdallah left for Paris.

Soilih held on for two years, himself surviving no fewer than four attempted coups.

He was a terrible leader. His drug and alcohol abuse, and his tendency to look to his witch doctor for strategic guidance, compounded his policy failures. Soon the treasury was empty, and the country was growing hungry.

When the witch doctor told Soilih he would be killed by a white man with a black dog, the increasingly mad president sent men to kill all the dogs on the island—an obviously fruitless task.

Deposed former president Abdallah watched Soilih’s implosion from the comfort of exile in Paris. Abdallah allied with two wealthy Comoran businessmen. Together they came up with a surprising plan. They would hire the man who had overthrown Abdallah two years ago to restore the former president to power.

They called Denard.

Back to the Comoros

The old mercenary was a desperate man. His attempted coup in Benin the year before had left him with a bullet in his skull and prison and death sentences in France and Benin. He accepted Abdallah’s contract—thus switching sides in a conflict for at least the third time in his career—and quickly spent millions of dollars of the conspirators’ money recruiting and arming his troops.

When the money ran out, a determined Denard sold a garage he owned and became a shareholder in “Abdallah, Inc.”

Denard bought a 200-foot trawler he renamed Masiwa, stocked it with weapons, and brought aboard 50 of his best men and a pet German Shepherd—the black dog of Soilih’s nightmares.

They sailed from France in March. On May 13, 1978, they slipped ashore wearing black uniforms, prophetic dog in tow. Killing four guards and cops en route to the presidential palace, they found Soilih drunk in bed with two young girls. “I should have known it would be you,” Soilih said to Denard.

Abdallah resumed his interrupted presidency. Sixteen days later, the imprisoned Soilih was shot dead, allegedly by Denard’s men.

And Denard reaped the rewards. Installed as chief of the 500-strong presidential guard—in effect, the military of the Comoros, equipped with machine gun-armed jeeps—Denard was widely considered the real power in the Comoros.

He recruited friends and fellow Europeans as guard officers. With his salary of more than $3 million a year, he built a luxurious estate on 1,800 acres. He married a hotel receptionist, his sixth wife, and had eight children. He converted to Islam. Or claimed to, at least.

Denard also claimed to have the support of the French government, which had been keen to retain some influence over its former colonies. But if that claim was true, Paris never publicly confirmed it.

But it seems Abdallah resented and feared Denard’s power. The Frenchman had, after all, helped overthrow rulers in Nigeria, Angola, and Yemen. After 11 years of unofficial joint rule, in 1989 there were rumors Abdallah planned to replace Denard as chief of the guard.

The timing seemed right. All over the world, old alliances were weakening. The poor nations of the world were throwing off the chains of superpower conflict, ejecting their agents and realigning their interests.

But Abdallah never got the chance for his own version of the Soviet Union’s perestroika, or “reform.” On the night of Nov. 26, the president was shot and killed in his bedroom.

Newspaper accounts, what few there were, varied wildly. At least one breathless article described a mercenary firing a rocket-propelled grenade into Abdallah’s bedroom. The scant press actually paying some attention assumed Denard or his men killed Abdallah. Everyday Comorans believed it, too. They rioted in the capital city of Moroni, chanting, “Assassin! Assassin!” when Denard appeared.