Where did the Modern Mercenary Industry Come From?

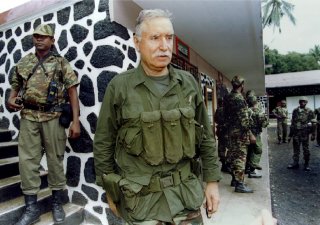

Meet the father of modern mercenary warfare.

“Who can and should be punished for these crimes?” Singer asked. “It is very clear that privatizing security actions only complicates the issue.”

But that was the point. The more the Pentagon relied on hired guns, the greater the distance between the government and the conduct and consequences of the wars it waged.

Mercenary playground

Michael Stock’s family had made a fortune in banking. In 1999, shortly after graduating from Princeton, he used a portion of that fortune to found, in Virginia, a non-profit organization called Landmine Clearance International.

Its mission statement: to “rehabilitate populated areas in the aftermath of armed conflict through land-mine clearance and explosive ordnance disposal.”

In 2007 Landmine Clearance International got a new and fancier-sounding name—Bancroft Global Development—and new headquarters in a $4-million mansion on Embassy Row in Washington, D.C.

And in 2008 Bancroft scored a new client: AMISOM, the 7,000-strong African Union peacekeeping force in Somalia, staffed mostly by Ugandans and funded by the U.S. to the tune of several hundred million dollars a year. With American money, AMISOM hired Bancroft to provide training for peacekeepers in close combat and bomb disposal. By 2010 Bancroft would be taking in $14 million in a year.

It took Bancroft four months and “a lot of lawyers and money” to set up facilities at the A.U.-controlled seaport-and-airport complex in Mogadishu, according to Somalia Report, an online publication run by adventurer and war correspondent Robert Young Pelton.

The new digs would expand to include rooms for rent for $155 a night plus a bar popular with military advisers, journalists, and visiting government officials.

Stock’s approach was careful, deliberate. “You better know the rules,” he said. After 17 years of war, those Somali bureaucrats who had survived were a hard and dangerous bunch. There were negotiations, mountains of paperwork, and not a few bribes to be proffered.

To staff its Somalia ops, Bancroft recruited two dozen veteran mercenaries—a mix of Europeans and South Africans. One of them was Richard Rouget, formerly of the Comoran presidential guard.

After a stint organizing safaris, Rouget had returned to the gun-for-hire business. In 2005, a South African court convicted him of illegally recruiting mercenaries to fight in the West African nation of Ivory Coast.

His fine was just shy of $9,000. But Rouget was evidently broke. He reportedly borrowed some money from a friend and raised some more leading a safari to Mozambique. Clearly badly in need of cash, in 2007 or 2008, it seems, Rouget signed on with Bancroft and flew to Mogadishu.

He was assigned to teach Ugandan troops, long experienced in forest fighting, how to do battle door to door, building to building. Though unarmed, Rouget routinely accompanied his trainees into the dust and clamor of urban fighting.

In five years of hard combat, the Ugandans and their allies, funded by the U.S. and trained by men like Rouget, steadily pushed back Islamic militants, gradually restoring an internationally-backed regime to Somalia after more than two decades of bloody warfare.

It was one of the first widely-sanctioned modern wars led, and in large part won, by mercenaries. The guns-for-hire helped Washington to keep its distance from Somalia and still wage war there.

Honoring the spirit of his mentor Bob Denard, that famed dog of war, Rouget told The New York Times he relished his work. “Give me some technicals”—gun-armed pickup trucks—“and some savages and I’m happy.”

David Axe served as Defense Editor of the National Interest. He is the author of the graphic novels War Fix, War Is Boring and Machete Squad.

This article first appeared in April 2020.

Image: Reuters