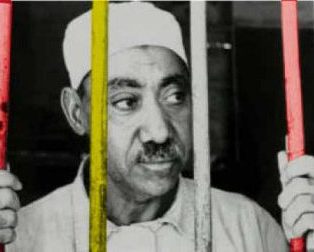

Qutb and the Jews

Mini Teaser: The conventional wisdom says Sayyid Qutb is the forefather of modern-day Islamic fundamentalism. What is less known is how the thinker's intense anti-Semitism and contempt for female sexuality contributed to this vulgar worldview.

THE WEST’S pollution of the lands of Islam was a main reason for Qutb’s propagation of jihad. The Koran enjoins the faithful to fight those who “believe not in Allâh . . . nor in the Last Day . . . nor forbid that which has been forbidden by Allâh and His Messenger . . . and those who acknowledge not the religion of truth.” While some Muslim exegeses maintained that jihad must be joined only in defense of the Islamic realm or people, the thrust of the traditional Muslim interpretation, to which Qutb also adhered (certainly in his last years), was that jihad should be waged against all unbelievers defensively and offensively in order, ultimately, to bring all the world’s peoples into the embrace of Allah. Or as Qutb put it: “If we insist on calling Islamic jihad a defensive movement, then we must change the meaning of the word ‘defense’ and mean by it ‘the defense of man’ against all those forces that limit his freedom.” (Qutb always insisted that real freedom was achieved only through submission to Allah and wholehearted acceptance of the truth of Islam.)

Qutb, says Calvert, saw jihad as the instrument of an essentially expansionist Islam. “For Qutb, as for the classical jurists, it is important that Islam be elevated to a position of power over [all] the peoples of the earth.”

This was the strategic vision. But as Calvert points out, Qutb in the 1950s and 1960s was aware of the weakness of contemporary Muslim societies and hence strove, in the first instance, to build up Muslim power and the cadres of the Islamic revolution, and then to tackle the “Near Enemy”—the Western-affiliated regimes—before dealing with the source of evil itself. (Qutb’s pupils, Ayman al-Zawahri, who studied directly under Qutb’s brother Muhammad Qutb, and Osama bin Laden, preferred to reverse this strategy for al-Qaeda: They reasoned that it was best to go for the “Far Enemy” first, which, once weakened, would be unable to prop up the Saudi and Egyptian governments. Then all would more easily fall before the Islamist storm.)

CALVERT PROVIDES a good review of Qutb’s intellectual and ideological development, but there is one serious elision, and this constitutes a major failing: the book does not thoroughly, let alone persuasively, deal with Qutb’s anti-Semitism. In the end, Calvert simply dismisses Qutb’s anti-Jewish assertions as an idiosyncratic matter of a personal, “‘paranoid’ style”—instead of squarely facing up to the wider implications of what Qutb’s case tells us about Islam and the Jews. Calvert uses the standard (historically inaccurate) apologetic arguments that the Islamic authorities never adopted a “persecutory posture” toward their Jewish minorities and that Jews, accorded a “relatively secure position,” were “tolerated” in Muslim societies, as compared with how their coreligionists fared in the Latin West. The histories of Muslim-Jewish relations in the lands of Islam by scholars such as Norman Stillman and Bernard Lewis do not support this description.

Calvert never says, simply, that Qutb was an anti-Semite; perhaps it is politically incorrect to forthrightly accuse a major Muslim thinker of such a predilection. But “the Jews” appear to have been important, if not central, to Qutb’s worldview, at least after the Arab disaster in Palestine in 1948. From that year onward Qutb was wont, like most contemporary Islamists, to refer to the Muslims’ “Crusader [i.e., Christian] and Zionist” enemies.

But Qutb’s anti-Semitism was religious and deep-rooted, originating in the Koran and its descriptions of Muhammad’s antagonistic relations with the Jewish tribes of Arabia (who simply rejected the Prophet and his message and were consequently slaughtered, enslaved or exiled by him), not in the contemporary struggle with Zionism. (Though the ongoing Arab-Israeli conflict, no doubt, exacerbated his anti-Jewish prejudices. He often compared what he saw as Jewish misdeeds in seventh-century Hejaz—the Jews turning their backs on divine revelation, trying to poison the Prophet and fighting the believers—and twentieth-century Palestine.)

In or around 1951 Qutb published an essay entitled “Our Struggle with the Jews” (reprinted as a book by the Saudi government in 1970). Calvert devotes a paragraph to this screed—but would have done well to elaborate further. In the essay, Qutb vilified the Jews, in line with the Koran, as Islam’s (and Muhammad’s) “worst” enemies, as “slayers of the prophets,” and as essentially perfidious, double-dealing and evil.

Qutb uses Nazi language. The Jews, he wrote:

Free the sensual desires from their restraints and they destroy the moral foundation on which the pure Creed rests, in order that the Creed should fall into the filth which they spread so widely on the earth. They mutilate the whole of history and falsify it. . . . From such creatures who kill, massacre and defame prophets one can only expect the spilling of human blood and dirty means which would further their machinations and evil.

Moreover, Jews, by nature, are “ungrateful,” “narrowly selfish” and “fanatical.” He continued, “This disposition of theirs does not allow them to feel the larger human connection which binds humanity together. Thus did the Jews (always) live in isolation.”

In his essay, written six years after the Holocaust, Qutb stressed that the battle with the Jews—now in the guise of Zionists—had raged for 1,400 years and continued. Typical of his thinking and style of argumentation is the following mendacious anecdote, proffered in a footnote: “While entering (Old) Jerusalem in 1967, the Jewish armies shouted, ‘Muhammad died and had fathered only daughters.’”

IN HIS introduction, Calvert presents Qutb as a supremely moral being. He was bent on propagating Allah’s message to humanity, and that message was beneficent and moral. So Calvert asserts: “Qutb never would have sanctioned the killing of civilians, which several of the militant groups committed. . . . Al-Zawahiri’s bloody war against the ‘Far Enemy’ took radical Islamism to a place that Qutb had never imagined.” Perhaps, in truth, Qutb’s imagination never technically went as far as envisioning large Muslim-piloted jet aircraft exploding into infidel skyscrapers. But the question, really, is whether he would have sympathized with and supported al-Qaeda’s campaign against the West. It is pointless to speculate. But the things Qutb wrote in his lifetime about the West and the United States (and the Jews) sound not very different from the contemporary railing of al-Zawahri and bin Laden.

Benny Morris is a professor of history in the Middle East Studies Department of Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. His most recent book is One State, Two States: Resolving the Israel/Palestine Conflict (Yale University Press, 2009).

Correction: The passage “While entering (Old) Jerusalem in 1967, the Jewish armies shouted, ‘Muhammad died and had fathered only daughters.’” appears as a footnote in the Saudi edition of "Our Struggle with the Jews." But it was added, posthumously, by the editor (see Ronald L. Nettler's Past Trials and Present Tribulations, which contains the essay's translation into English), and I should have noted that.

Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review