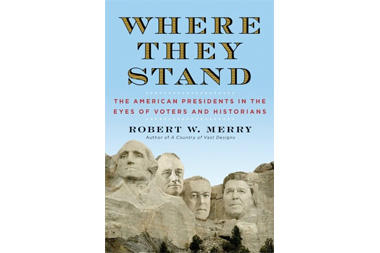

The Great White House Rating Game

Mini Teaser: Robert Merry’s new book explores the academic impulse to assess the presidents—but with a twist. He melds contemporaneous judgments of the electorate with academic polls to yield an engaging history.

WHO WERE the greats, and how do we discern them? Here things seem to get a bit mushy. Merry avoids the term “great.” Instead, he lists six “Leaders of Destiny” who possessed premier qualities of political perceptiveness, a broad transformative vision and political adroitness. They are the standouts of the dozen presidents who served two terms and were succeeded by a member of their own party: Washington, Jefferson, Jackson, Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin D. Roosevelt. Early in the book, the author identifies FDR and Ronald Reagan as the two greatest presidents of the twentieth century and tells us near the end that he personally believes that Reagan was a Leader of Destiny. All the same, he punts on applying the label and comments that “history has yet to render a clear judgment on his place in the presidential pantheon.” Why, then, all the other challenges to conventional ratings wisdom throughout this book?

The six “Destinarians” were perennial choices as great or near great in the various polls referenced, yet they are too prominent to require detailed discussion. Two have slid a bit in recent years. The C-SPAN polls of 2000 and 2009 both rate Jefferson seventh, an adjustment that probably reflects growing awareness of the disastrous nature of his second term. They also put Andrew Jackson at thirteenth, likely a reaction springing from growing consciousness of both the way in which he ruthlessly persecuted Native Americans and the damage done by his primitive policies regarding money and finance.

One phenomenon cuts across the author’s categories—the difficulty of serving two unblemished terms. Nineteen men have served more than one term as president. Their collective experience demonstrates that it is very difficult to negotiate more than four years in the office without significant challenges.

Consider Jefferson, whose first term was marked by the Louisiana Purchase and a general sense of national progress. He was reelected overwhelmingly but saw his second term engulfed in the maritime tensions with England that grew out of the Napoleonic wars. Or take his designated successor, Madison, who, Merry’s stout defense notwithstanding, was dragged into a war that went badly in many ways—the failed invasion of Canada, serious losses at sea, the British raid on Washington, the near secession of New England—until the successful defense of Baltimore and Andrew Jackson’s triumph at New Orleans provided an appearance of victory.

Move up three-quarters of a century to Grover Cleveland’s second term and the severe economic depression that broke out just months after his inauguration, leaving him presiding over national misery for the remainder of his presidency and repudiated by his own party in favor of William Jennings Bryan.

Or fast-forward to Woodrow Wilson, who brought the progressive movement to a peak during his first term (an achievement considerably undervalued by Merry), won reelection, and then found himself taking the nation into a war for which it was unprepared and that he handled poorly. Or Franklin D. Roosevelt, who seemed at the end of his first term on the way to beating the Great Depression and transforming American politics, only to see his second term give rise to a new economic collapse and the folly of the court-packing plan.

Or Harry Truman, who, after initial stumbles, committed the United States to containment of the Soviet Union and the Marshall Plan, backed civil rights more strongly than any Democratic president before him and won election in his own right only to be caught up in the Korean stalemate, McCarthyism and small-bore scandals. (Merry, I think, exaggerates when he categorizes Truman as a failed war president. It is fair to say his administration bungled policy toward Korea before the North Koreans invaded, but today’s free and prosperous South Korea provides sufficient moral vindication for Truman’s decision to go to war. A political failure is not necessarily a historical one.)

Some second-termers who ran into trouble—Nixon and Clinton come to mind—need only look in the mirror to affix the blame. Others were capable men blindsided by events beyond their control. Popular majorities rarely make distinctions. Historians should. Most presidencies of consequence are mixtures of failure and achievements that require a difficult sorting out.

In the nature of things, Merry cannot—and should not—attempt a summary discussion of every single president, but he at least touches on most of them. One omission, however, is extraordinarily puzzling. He says next to nothing about John F. Kennedy, telling us that JFK “never had a chance to leave a substantial stamp upon the nation.”

Is that really the case? Kennedy was among the most charismatic of presidents, provided exemplary leadership through the most dangerous nuclear confrontation in human history and aligned the Democratic Party squarely with the cause of full civil rights for African Americans. He was in office for nearly three years. His death was a national trauma. Three generations later, his party has failed to produce a leader with a similar combination of substance and popular appeal. General public-opinion surveys tend to rank him among the greatest ever. The C-SPAN respondents, mostly academics, placed him eighth in 2000 and sixth in 2009. The latter survey put him ahead of Thomas Jefferson, Woodrow Wilson and Andrew Jackson. Surely his presidency deserves a page or two of evaluation.

ONE CONCLUDES that this edition of the ratings game is still a trifle uncertain about the rules. The forty-two-person list, neatly divided into five grading categories, never materializes. There is no attempt to discuss the skills required for a successful presidency. How important, for example, is executive experience? (Five of the six Leaders of Destiny served either as governors or commanding generals, although Jefferson’s tenure as governor of Virginia was lackluster, and Lincoln, the one exception, is widely considered the greatest of them all.) Quite a number of presidents are discussed trenchantly, but a few make only cameo appearances. The Leaders of Destiny are a reasonable approximation of a greatness list, but even here one can raise questions. Jefferson and Jackson, for example, may have been great men, but they also were advocates of small government, slave owners who believed in a decentralized agrarian republic, and hostile toward industry and capitalist finance. Did they actually grasp their nation’s destiny? Was Lincoln really a shrewd political manipulator or, as he himself insisted, a leader who was controlled by events he muddled through?

Systematic analysis is not Robert Merry’s game. Delighting in provocative observation, he seems more attracted to horseshoes and hand grenades than to analytical political chess. Most readers of this thoughtful and readable volume will find something in it to provoke them—and likely enjoy the provocation.

Alonzo L. Hamby is Edwin and Ruth Kennedy Distinguished Professor of History at Ohio University. He has written extensively on Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry Truman and is completing a biography of FDR.

Pullquote: Nineteen men have served more than one term as president. Their collective experience demonstrates that it is very difficult to negotiate more than four years in the office without significant challenges.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review