The Afghan Withdrawal That Isn't

This plan to reduce force levels in Afghanistan seems to be a maintenance of the status quo.

One of the most obvious, yet often-ignored facts regarding President Barack Obama’s decision to withdraw troops from Afghanistan in 2013 is that it wasn’t a withdrawal at all. It was merely a transference of primary security responsibilities from the U.S.-led coalition to the Afghan government; a residual force would remain in the country to advise and assist the Kabul government in its enduring struggle against the Taliban and other insurgent groups. Thus, it should hardly surprise anyone that the United States still has more than eight thousand troops in-country—though that number seems to vary depending on who’s doing the counting.

So it would appear history is repeating itself yet again following the news that the United States is preparing to withdraw thousands of troops as part of an agreement with the Taliban whereby the latter would, among other things, commit to never allowing Afghanistan to become a safe-haven for terrorists ever again. If reached, then the agreement would be extraordinary, as it would mark the first time the United States and the Afghan government have achieved any step towards peace with the Taliban after nearly eighteen years of bitter fighting.

But, like Obama administration, the Trump administration wouldn’t be doing anything new. As the Washington Post report entails, even if an agreement were reached, the end state would still be between eight thousand and nine thousand troops in-country, which is roughly the same number of troops that were there when Donald Trump entered office. Again, the number of U.S. troops in Afghanistan seems to vary depending on the source, but even if the end state is a combination of American and coalition troops, it’s still a major involvement in a war the president once promised to wind down. In other words, the United States would find itself right back where it started two years ago.

The fact that the United States and its allies would continue to maintain a presence in the country shows this is hardly a plan for ending American involvement in Afghanistan’s affairs or the war. For all of President Donald Trump’s talk of his personal preferences, there’s no indication a complete withdrawal is being seriously considered in Washington. As the Washington Post report also indicates, Gen. Austin Miller, commander of the Resolute Support Mission and all U.S. forces in Afghanistan, intends to keep Bagram Airfield in business, and U.S. troops are likely to maintain a presence in Kabul. This doesn’t include troops from allied countries that may also continue operations.

From the tactical all the way up to the political level, dangers abound. Whether the agreement with the Taliban is reached or not, some level of violence is sure to persist in a country that’s seen little other than war for the last four decades. For the remaining U.S. troops, they’ll be incapable of making any impact in stemming the violence; even over one hundred thousand wasn’t enough to bring the Taliban to heel at the height of the war during the “surge” era. Any U.S. and coalition troops remaining in Afghanistan following negotiations will be forced deeper into their safe zones and hunker down in bases like Bagram Airfield, which will come to resemble fortresses. While the Taliban will likely avoid inflicting violence against U.S. and coalition forces for fear of reprisal, the fact is the latter’s mere presence exposes them to violence. While they can take measures to protect themselves and avoid violence, it’ll only raise questions as to what purpose their presence serves, questions that’ll be posed the next time another American servicemember is reported killed in action.

Upon closer examination, this plan to reduce force levels in Afghanistan seems to be a maintenance of the status quo. The most likely explanation is that President Trump has largely conceded a total withdrawal from Afghanistan and is doing what many presidents have done before him—splitting the difference. A complete withdrawal would be impossible to implement politically, and the national-security establishment will likely slow-roll any such order, so Trump is seeking to reduce troop levels to create the impression the war is nearing its end and, hopefully, bolster his re-election bid.

There may be sound logic behind this strategy. Early polling on the 2020 election reveals the endless “War on Terror” doesn’t register as a major concern for most voters. Any word that Trump is withdrawing troops from one of America’s longest wars is likely to serve as a nice bonus, especially when candidates on the other side are attempting to seize upon the issue as a central part of their election campaigns. The downside, of course, is that the war would continue well past 2020 and possibly into 2024.

It has become increasingly clear that ending involvement in any war is completely out of character in Washington. In Vietnam, even with North Vietnamese forces bearing down on Saigon, American diplomats were still looking for an excuse to stick around and save the South. Contrary to popular memory, the U.S. withdrawal from Beirut in 1984 split the administration and initially emboldened it to remain on course, despite the fact that 241 U.S. Marines were killed in a single day. In Iraq, the U.S. liberated Kuwait in 1991, continued bombing Iraq for twelve years, then invaded and liberated Iraq, battle an insurgency, before finally handing off the country to Baghdad’s security forces in 2011. But it wasn’t a total withdrawal, and, within three years, the United States was back in Iraq to save the country teetering on the brink from the Islamic State’s onslaught.

Even if the United States were to commit to a complete withdrawal from the Afghanistan, the United States is likely to be involved militarily on an indefinite basis. The conditions are such that the country may very well become a safe haven for terrorists once more; any intelligence regarding threats to the United States or, God forbid, a terrorist attack on the American homeland, would rightfully trigger a U.S. military response. This is a fact of life even proponents of total withdrawal, like the Catholic University’s Gil Barndollar, concede. There seems to be a grudging consensus among supporters and detractors of the war that the United States will never completely rid itself of Afghanistan; they don’t call it the “graveyard of empires” for nothing, after all. Even places like Libya and Somalia, where the United States was thought to have departed from decades ago, still see American military involvement on a routine, though shadowy, basis. The question of what purpose keeping American boots on the ground in an enduring basis in Afghanistan serves any longer is the dividing line.

Though heavily-derided for saying so, President Trump was bluntly acknowledging reality when he hinted that any attempt to win the war in Afghanistan would result in the deaths of untold millions. The Taliban refuse to die and continue to hold large swathes of territory. At this point, only absolute destruction will deliver the military victory war supporters desire, at great human, material, and political cost to all involved. If absolute destruction isn’t an option and neither is “muddling along,” then President Trump, along with the other candidates for president in 2020, must accept that the war will never end on terms favorable to the United States and that the fighting will continue—with the door to a renewed American involvement always open.

The question left for the president to answer is whether to continue as a central player or watch the tragedy continue to unfold from across the street, remaining ready to run across into the fray once more if necessary.

Edward Chang is a defense, military, and foreign policy writer. His writing has appeared in The American Conservative, The Federalist, The National Interest, and War Is Boring. He can be followed on Twitter at @Edward_Chang_8.

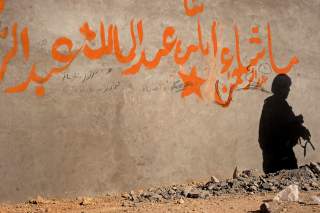

Image: Reuters