China vs. Japan: Asia's Other Great Game

Beijing and Tokyo will undoubtedly compete long after U.S. foreign policy has evolved.

COMPETITION BETWEEN countries does not inherently lead to aggression, or even particularly contentious relations. Indeed, looking at Sino-Japanese relations from the vantage point of 2017 may distort just how vexed their ties traditionally have been. For long periods of its history, Japan looked to China as a beacon in a sea of murk—as the most advanced civilization in Asia and as a model for political, economic and sociocultural forms. While at times that admiration was perverted into an attempt to assert equality, if not superiority, as during the Tang era (7–10 c.) or a millennium later, during the rule of the Tokugawa shoguns (17–19 c.), it would be a mistake to assume there was no positive element to the interaction between the two. Similarly, Chinese reformers understood that Japan had achieved success in modernizing its feudal system in the late nineteenth century to a degree that made it, for a while, a model. It was not an accident that the father of the 1911 Chinese Revolution, Sun Yat-sen, spent time in Japan during his exile from China in the first years of the twentieth century. Even after Japan’s brutal invasion and occupation of China during the Pacific War, the 1960s and 1970s saw Japanese politicians such as Prime Minister Tanaka Kakuei reach out to China, restore relations and even contemplate a new era of Sino-Japanese relations that would shape Cold War Asia.

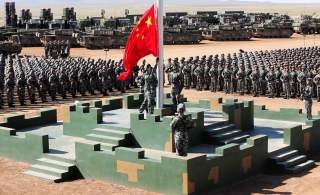

Such fragile hopes, not to mention mutual respect, now seem all but inconceivable. For over a decade, Japan and China have been locked into a seemingly intractable downward spiral in relations, marked by suspicion and increasingly tense maneuvering on security, political and economic fronts. Except for the actual Japanese invasions of China in 1894–95 and 1937–45, the history of Japanese-Chinese competition was often as much rhetorical or an intellectual exercise as it was real. The current competition is more direct, even while taking place in an environment of Sino-Japanese economic integration and globalization.

The current atmosphere of Japanese-Chinese dislike and mistrust is marked. A series of public-opinion polls carried out by Genron NPO, a Japanese nonprofit think tank, in 2015–16 revealed the parlous state of relations. Fully 78 percent of Chinese and 71 percent of Japanese polled in 2016 believed relations between their two countries were either bad or relatively bad. Both publics also saw significant increases from 2015 to 2016 in expectations that future Japan-China relations would worsen, from 13.6 percent to 20.5 percent in China and from 6.6 percent to 10.1 percent in Japan. When asked if Sino-Japanese relations posed a potential source of conflict in Asia, 46.3 percent of Japanese responded affirmatively while 71.6 percent of Chinese agreed. Such findings track with other polls, such as a 2016 survey by the Pew Research Center, which found that 86 percent of Japanese and 81 percent of Chinese held unfavorable views of each other.

The reasons for this public distrust reflect, in large part, the outstanding policy disputes between Beijing and Tokyo. The Genron NPO poll found that over 60 percent of Chinese, for example, cited both Japan’s lack of apology and remorse over World War II, and its September 2012 nationalization of the Senkaku Islands, claimed by Beijing as the Diaoyu Islands, for their unfavorable impression of Japan.

Indeed, the history question continues to dog Sino-Japanese relations. China’s leaders have astutely used it as a moral cudgel with which to bash Tokyo. Pew’s polling thus found an overwhelming 77 percent of Chinese claiming that Japan had not yet sufficiently apologized for the war, yet over 50 percent of Japanese believing their country had apologized enough. Controversial visits to Yasukuni Shrine, where eighteen Class A war criminals are enshrined, by current prime minister Shinzo Abe in December 2013 continued a spate of provocations in Chinese eyes that seemed to downplay Japan’s remorse for the war at the very time Abe was pursuing a modest military buildup and challenging China’s claims in the East China Sea. A visit to China in the spring of 2017 revealed no abatement of anti-Japanese portrayals on Chinese television; on any given night, at least a third if not more of prime-time dramas on stations from all of China’s major provinces were about Japan’s invasion of China, given verisimilitude thanks to actors speaking fluent Japanese.

If the Chinese are focused on the past, the Japanese are most concerned about the present and future. In the same polls, nearly 65 percent of Japanese claimed that the ongoing Senkaku Islands dispute accounted for their negative view of China, while over 50 percent cited the “seemingly hegemonic actions of the Chinese” for leaving an unfavorable impression. Overall, 80 percent of Japanese polled by Pew responded that they were either very or somewhat concerned that territorial disputes with China could lead to military conflict, versus 59 percent of Chinese.

These negative impressions and fears for war come despite nearly unprecedented levels of economic interaction. Even with China’s recent economic slowdown, according to the CIA World Factbook, Japan was China’s third-largest trade partner, accounting for 6 percent of its exports and nearly 9 percent of its imports; China was Japan’s largest trade partner, taking 17.5 percent of its exports and providing a full quarter of its imports. Though exact numbers are difficult to ascertain, it has been claimed that Japanese firms directly or indirectly employ as many as ten million Chinese, most of them on the mainland. The neoliberal assumption that greater economic ties raise the threshold for security conflicts is being tested in the Sino-Japanese case, with both proponents and critics of the concept able to claim that so far, their interpretation is correct. Since the downturn in relations during the administration of Junichiro Koizumi, Japanese academics, such as Masaya Inoue, have described the relationship as seirei keinetsu: politically cool, economically hot. That relationship is reflected in another way by the surging number of Chinese tourists to Japan, who totaled nearly 6.4 million in 2016, whereas the China National Tourism Administration claims that nearly 2.5 million Japanese visited China, ranking second after South Korean tourists.

Yet the growing Sino-Japanese economic relationship has not been left unaffected by geopolitical tensions. Chinese protests against Japan over the Senkaku dispute led to steep declines in Japanese foreign direct investment in China during 2013 and 2014, with year-on-year investment dropping by 20 and 50 percent, respectively. These declines were accompanied by a corresponding increase in Japanese investment in Southeast Asia, including in Indonesia, Thailand, Malaysia and Singapore.

Negative attitudes towards China on the part of Japanese business have been mirrored in the political and intellectual sphere. Japanese analysts have been concerned about the long-term implications of China’s growth for years, but such concerns turned into open worry, particularly once China’s economy overtook Japan’s, in 2011. Since the crisis in political relations caused by repeated incidents in the Senkaku Islands starting in 2010, policymakers in Tokyo interpreted Beijing’s actions as flexing newfound national muscle, and they grew frustrated with the United States for its seemingly cavalier attitude towards Chinese assertiveness in the East China Sea. At one international conference in 2016, which I attended, a senior Japanese diplomat harshly criticized Washington and other Asian capitals for countering China’s expansion in Asian waters with nothing but rhetoric, and warned that it might soon be too late to blunt Beijing’s attempts to gain military dominance. “You don’t get it,” he repeated in unusually blunt language, decrying what he (and perhaps his superiors) saw as undue complacency about China’s encroachment throughout Asia. It is not difficult to get the sense that China is seen by some leading thinkers and officials as a near-existential threat to Japan’s freedom of action.

As for Chinese officials, they are all but dismissive of Japan and its future prospects. One leading academic told me that China already has more wealthy citizens than the entire population of Japan, so that there could be no competition between the two; Japan simply can’t keep up, he asserted, so its influence (and ability to oppose China) was doomed to evaporate. Similarly, a visit to one of China’s most influential think tanks revealed an almost monolithically negative view of Japan. Numerous analysts expressed their skepticism about Japan’s intentions in the South China Sea, perhaps revealing a concern for increased Japanese activity in the region. “Japan wants to get out from under the [postwar] U.S. system and end the alliance,” one analyst asserted. Another criticized Tokyo for “playing a disruptive role” in Asia, and for creating a loose alliance against China. Underlying many of these feelings among Chinese elite is a refusal to accept Japan’s legitimacy as a major Asian state, tinged with more than a little fear that Japan is the only Asian nation, along perhaps with India, that can prevent China from reaching certain goals, such as maritime dominance in Asia’s inner seas.

The sense of distrust between China and Japan reveals not only long-standing tensions, but also a window into the insecurities felt by both countries as they contemplate their respective positions in Asia. These insecurities and tensions combine to create the competition that each is waging against the other, even as they maintain extensive economic relations.