China vs. Japan: Asia's Other Great Game

Beijing and Tokyo will undoubtedly compete long after U.S. foreign policy has evolved.

Since returning to power in 2012, Prime Minister Abe has moved to increase Japan’s defense spending and expand its security partnerships around the region. After a decade of decline, each of Abe’s defense budgets since 2013 has modestly increased spending, now totaling roughly $50 billion per year. Next, in reforming postwar legal restrictions, such as the ban on arms exports or the ban on collective self-defense, Abe has attempted to offer Japan’s support as a way to blunt some of China’s growing military presence in Asia. Sales of maritime patrol vessels and airplanes to countries including Malaysia, Vietnam and the Philippines are designed to help build up the capabilities of these nations in their territorial disputes with China over the Spratly and Paracel Islands. Similarly, Tokyo hoped to sell Australia its next generation of submarines, as well as provide India with amphibious search and rescue aircraft, though both of these plans ultimately fell through or were put on hold.

Despite such setbacks, Japan has increased its security cooperation with a variety of nations in Asia, including in the South China Sea area. It has formally joined the Indo-U.S. Malabar naval exercises, and sent its largest helicopter carrier to the July 2017 exercise after three months of port visits in Southeast Asia. The Japanese coast guard remains actively engaged throughout the region, and plans to set up a joint maritime safety organization with Southeast Asian coast guards to help them deal not only with piracy and natural disasters, but also to improve their ability to monitor and defend disputed territory in the South China Sea. Most recently, Foreign Minister Taro Kono announced a $500 million maritime security initiative for Southeast Asia, designed to help build capacity among nations in the world’s most congested waterways.

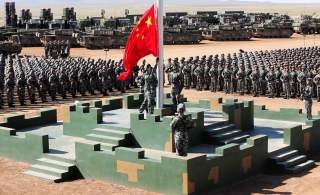

If Tokyo has attempted to build bridges to Asian nations in a cooperative gamble, Beijing has constructed artificial islands in an attempt to be recognized as the dominant Asian security power. China faces a more complicated security equation in Asia than Japan, given its assertive claims in the East and South China Seas, and its territorial disputes with many of its neighbors, including larger nations such as India. The dramatic growth of China’s military over the past two decades has resulted not merely in a more capable navy and air force but in policies designed to defend and even extend its claims. The high-profile land reclamation and construction of bases in the Spratly Island chain exemplify Beijing’s decision to assert its various claims and back them up with a military presence that dwarfs those of other contestant nations in the South China Sea. Similarly, the increase in Chinese maritime exercises in areas far from its claimed territory, such as the James Shoal, near Malaysia, or in the Indian Ocean, has worried nations that see Beijing’s increasing capabilities as a potential threat.

China has, of course, attempted to assuage these concerns through maritime diplomacy, such as engaging in an ongoing set of negotiations with ASEAN nations over a Code of Conduct in the South China Sea, or conducting joint exercises with Malaysia. Yet repeated acts of intimidation, or direct warnings to Asian nations, have blunted any goodwill, forcing smaller states to consider how far to acquiesce in China’s expansionist activities. Adding to the region’s unease was Beijing’s flat rejection of The Hague’s Permanent Court of Arbitration’s ruling against Beijing’s South China Sea claims. Unlike Japan, moreover, China has not sought to win friends by providing defensive equipment; the bulk of China’s military sales in Asia goes to North Korea, Bangladesh and Burma, forging a loose grouping, along with Pakistan (the largest recipient of Chinese arms transfers), that is isolated from those nations cooperating with both Japan and the United States.

China’s approach, a combination of realpolitik and limited machtpolitik, is more likely to secure its goals, at least in the short run, if not longer. Smaller nations are under no illusions that they can successfully resist China’s encroachments; what they hope is either for a natural moderation of Beijing’s behavior or an overreach that will allow communal pressure to influence Chinese decisionmaking. In this calculation, Japan appears primarily as a spoiler. While Tokyo is able to protect its own territories in the East China Sea, it knows that its power in the region is limited. This mandates not only a continuing, if enhanced, alliance relationship with the United States, but also an approach that helps complicate Beijing’s decisionmaking, such as by providing defensive equipment to Southeast Asian nations. Tokyo understands that it can potentially help disrupt, but not deter, Chinese expansion in Asia. Put differently, Asia is faced with competing security strategies from its two most powerful nations: Japan seeks to be loved; China, feared.

A DEEPER manifestation of Sino-Japanese rivalry is the model for national development that each implicitly offers for Asia. It’s not that Beijing expects governments around the Pacific to adopt communism or that Tokyo looks to help install parliamentary democracy. Rather, it is a more fundamental question of how each state is viewed by its neighbors and how much influence each state may have in the region thanks to perceptions of its national strength, governmental effectiveness, social dynamism and opportunities provided by its system.

It should be acknowledged that this is an extremely subjective approach, and the evidence for determining which of the two countries is more influential will more likely be anecdotal, inferential and indirect than explicitly discoverable. Nor is this question of serving as a model the same as the ubiquitous concept of soft power. Soft power is usually defined as an element of national power and, more specifically, the attractiveness of a particular system in creating the conditions through which that state can achieve policy goals. While both Beijing and Tokyo are undoubtedly interested in advancing their state interests, that is a question distinct from how each is viewed and the benefits from the policies they pursue.

Long gone are the days when a Mahathir Mohamad could declare Japan a role model for Malaysia, and when even China considered Japan’s modernization model a paradigm. Tokyo’s hopes to leverage its economic ties with Southeast Asia, the so-called “Flying Geese” model, into broader political influence was derailed by China’s rise in the 1990s. With Beijing being the largest trading partner for all Asian states, it occupies a central position. Yet Sino-Asian relations have remained largely transactional, due both to lingering concerns over Beijing’s assertiveness and fears of being economically overwhelmed. From a short-term perspective, China may appear more influential thanks to its economic power, but that too has translated only fitfully into political gains. Nor has there been an increase in Asian nations attempting to mimic China’s political model.

Instead, both Tokyo and Beijing continue to jockey for position and influence. Each treats with largely the same set of Asian actors, thus offering what Asians consider an almost market-based competition, in which smaller states are able to drive better deals than they would if dealing with either power alone. Moreover, both China and Japan base their policies in part on their perceptions of U.S. policy in Asia. Japan’s alliance with the United States serves in essence to merge Tokyo and Washington into one bloc versus Beijing, while also creating an underlying uncertainty as to American intentions. Japanese concern over the credibility of American promises to remain engaged in the Asia-Pacific drives Tokyo’s military modernization plans, in part to be a more effective partner and in part to avoid overdependence. At the same time, uncertainty over America’s long-term policy enhances Japan’s desire to deepen relations and cooperation with India, Vietnam and other nations that share its worries about China’s growing military strength. Similarly, Beijing’s response to the Obama administration’s involvement in the South China Sea territorial disputes was a program of land reclamation and base building in the Spratly Islands. The same could be said for China’s financial and free-trade initiatives, which are designed at least in part to blunt TPP, which was championed though not started by Washington, or the continued influence of the World Bank in regional lending.

From a mere material perspective, Japan should come off worse in any direct competition between the two nations. Its economic glory days are far behind it, and it never successfully translated its still comparatively powerful economy into political influence. Perceptions of its sclerotic political system add to the sense that Japan will likely never again regain the dynamism it showed in the postwar decades.

Yet as a stable democracy, with a largely content, highly educated, healthy population, Japan is still regarded as the benchmark for many Asian nations. Having long ago tackled its pollution problem, and with a low crime rate, Japan offers an attractive model for developing societies. Its benign international policies and minimal overseas military operations, combined with its generous foreign aid, make Japan the most admired country in Asia, according to a 2015 Pew Research Center poll—71 percent of respondents voiced a favorable view. China garnered only a 57 percent approval rating, with fully one-third of respondents having a negative view.