The Enduring Importance of Nathan Glazer

Like a number of his fellow New York intellectuals, Glazer’s life remained poised between the little magazine and the Academy.

Nathan Glazer, who died last month at age ninety-five, enjoyed an illustrious career that spanned seven decades and the fields of sociology, public policy, politics and urban studies. He wrote on the myth of the American melting pot, the nature of American communism, the unsavory methods of Senator Joseph McCarthy, the perils and importance of affirmative action, the social failure of modern architecture and on the limits of social policy. Glazer’s intellect was voracious, his mind perpetually curious, open and unpredictable.

Politically, Glazer was equally unplaceable, a man initiated into an obscure and tiny group of American Marxist Zionists as a college student during the Depression, who became a staunch anti-Communist in the post war years, then a critic of the New Left and liberalism in the sixties. A vocal foe of affirmative action in the seventies, he was decried as a neoconservative by the Left only to change his views in the 1990s, leading many conservatives to see him as a wholly “unreliable” ally.

And they were on to something. It is precisely Glazer’s “unreliability,”—a refusal to follow a party line—that defines both his social science work and his political views. In his acute mind, theoretical purity could never match the messiness, the confusion of facts that the world presents to us.

Glazer has jokingly confessed to being a man of “weak commitments,” a statement that could only have come from a man who grew up in a world of intense and overwhelming political and intellectual commitments. He stormed the ramparts time and time again; against Joseph Stalin and the Soviet Union, against American communism, against the New Left, and against political correctness. But his capacity for intellectual combat has never distorted his essential openness, his willingness to live with intellectual and political uncertainty. Most of us retreat from uncertainty into ideology; Glazer found in it a sandbox for his active and playful mind.

In this sense Glazer is perhaps distinct even from the brilliant and iconoclastic group of writers with whom he spent much of his life arguing, known as the New York intellectuals. The New York intellectuals were a new phenomenon in American intellectual life: a bunch of poor kids, mostly children of Jewish immigrants, who grew up outside the intellectual establishment and through second generation pluck and striving and talent pushed their way to the very forefront of American culture.

The New York intellectuals were distinguished early on by two defining interests—obsessions really. They were young converts to the cause of Marxist radicalism during the Depression years and madly in love with literary modernism. Marxism—though foreign to the American body politic—burned through the immigrant neighborhoods of New York and the intellectual precincts of Greenwich Village, a utopian fever dream that captured the imaginations of writers, artists and laborers alike. The Modernist movement, equally rebellious, artistically utopian and not yet accepted by the Academy, was just as intoxicating for young intellectuals. These European inventions were transmuted into central concerns of American political life through the powerful writing of the New York Intellectuals.

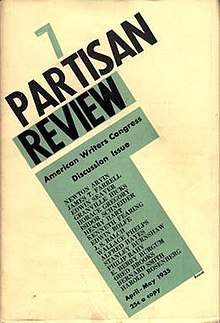

Glazer would first encounter these ideas in Partisan Review a journal begun in 1934 by Philip Rahv and William Phillips dedicated to these twin causes. Early on, Rahv and Phillips and their magazine lived inside the orbit of the American Communist Party. But the party’s heavy-handed Stalinism saw no place for the politically untamable and culturally subversive strains of Modernism. For the writers gathered around Partisan Review there was no contest. They took their magazine and exited the Party, stage Left, choosing intellectual independence over party line. Observing Stalin’s murderous rampage against fellow party members in the thirties, the Partisan Review group developed a sophisticated Marxist critique of Soviet communism that by the forties had evolved into a deeper one of Marxism-Leninism itself. As would-be revolutionaries, they were appalled by Stalin’s lethal totalitarianism and its cost in human life; as writers they were aghast at his assault on intellectual freedom. Casting off their Marxism in the postwar years, they came to embrace American democracy.

In hindsight all this dabbling in revolution feels remarkable. But remember that at this time Nathan Glazer was not yet twenty and his fellow New Yorkers were not yet into their thirties. Glazer would write that during these years, his fellow “intellectuals did not then know much about the politics of their own country,” and “their knowledge of [the Soviet Union] was as abstract as their knowledge of . . . the political and economic world.” And it should be remembered that far older men and women took far longer to see as clearly as Glazer and his friends ultimately did.

Out of this experience came an understanding for Glazer and his fellow New York Intellectuals of the perils of ideology, of grand theories that claimed to explain everything but instead blinded one to what Lionel Trilling called “the variousness and possibility” of life. Their radical youth had also given the New Yorkers great skill in polemic and argument, which could prove equally seductive—and equally problematic. The excesses of brilliance, the arrogance of theory could betray even people with discerning minds.

No New Yorker learned this lesson more thoroughly or thoughtfully than Nathan Glazer. No one became less enchanted with theory, with the abstract generalizations that thrilled with their grand visions but just as surely betrayed the complexities, the unreliability, of life itself which could not be shoehorned into any theoretical model, no matter how far-reaching, how elegantly argued, how sophisticated its reasoning.

“The old New York intellectual style of pronouncing judgments on a basis of less than adequate knowledge in politics and literature could not survive: It was specialize or die,”

Glazer would write in his later years. Leaving Marxism behind, Glazer in the years after City College gravitated to sociology. It still gave him the chance to explore big ideas, to work at the intersection of politics and social policy and social relations.

His personal experience equipped him to write on The Social Basis of American Communism (1961). The young sociologist neatly turned the tables in his exploration of the American Communist Party’s appeal to various immigrant groups, using ethnicity as the lens to view the class struggle, and embarked on a life-long study of America’s “ethnic pattern” that would lead, through a number of early essays in Commentary magazine, to his groundbreaking study of 1963 Beyond the Melting Pot, written with Daniel Patrick Moynihan.

Like a number of his fellow New York intellectuals, Glazer’s life remained poised between the little magazine and the Academy. He spent seven years at Commentary magazine as an assistant editor while getting his degree, covering a social science beat, The Study of Man — designed just for him. It allowed him to survey the work of his newly chosen profession and to follow his own interests. The young man emerging from the thickets of Marxist abstraction was drawn to sociology’s interest in the empirical, the concreteness of fact. But from the beginning, he also recoiled at sociology’s misguided attempt to make a science of itself, to believe that statistics and questionnaires and polls could produce scientific certainty. After all, Marxism, too, had claimed to be a science. Glazer was content with a more humble approach to the world.

Wary of theory and immune to the purely statistical, Glazer found his place in an imaginative sociology based on research but not limited to the purely quantifiable, producing work that allowed space for his own creative mind to take flight. The key to Glazer’s unique approach can be found in his beautiful essay on two giants of his field, Tocqueville and Riesman, one a nineteenth century French proto-sociologist, the other his mentor, David Riesman, with whom he had worked on The Lonely Crowd.

What he appreciates in these men are their “leaps of imagination.” While sociology cannot “dismiss the [central] significance of empirical work,” “ a large thesis, with implications for many areas of life, is not easy to encompass in detailed empirical studies, which try to reduce the thesis to elements that can be objectively measured and tested.” Glazer himself demurred from the grand generalization, partly out of a certain humility, but also because his mind simply did not work that way. In fact, Glazer’s method seems to be the exact opposite. Burrowing into details he builds from the bottom up, enlarging the significance of each one till the sum of myriad parts seems to become much greater than the whole.

Writing of the austere theoretical constructions of the great emigre political philosopher Hannah Arendt, for whom he had much admiration, he nonetheless notes that she had no use for “the social and its grubby ordinariness,” the “cussedness” of reality. These are of course the things Glazer himself revels in. Glazer’s very method of deduction is fueled by contradictions that undermine theory. Theorists build beautiful, logical structures; Glazer’s essays constantly run into contradictions of fact and argument that lead to larger if less “beautiful” truths about how Americans live, how public policy works—or doesn’t, how society organizes itself and ultimately how we as humans understand our own identities.