The Enduring Importance of Nathan Glazer

Like a number of his fellow New York intellectuals, Glazer’s life remained poised between the little magazine and the Academy.

Even Glazer’s writings on architecture and urbanism show the same suspicion of grand designs for cities or housing developments in favor of the wisdom and modesty embedded in the jumble of an ordinary city street, one built from the bottom up, which manages to reflect the contradictory yet somehow compatible desires and needs of its inhabitants. He gives a nod to the Italian immigrants of San Francisco’s Castro and New York’s Greenwich village for their culturally inherited ability to create a sense of community through small storefronts and cafes and whose collective, if only partly conscious, understanding of urban life was far greater than modernist geniuses and would-be master city builders like Le Corbusier.

While one usually associates the scale of a thinker’s vision with the duration of his ideas, the continuing relevance of Glazer’s work lies in its very specificity. His 1953 Commentary essay “America’s Ethnic Pattern,” one of the first explorations in his lifelong preoccupation with ethnicity, is as remarkable to read today as it was when it was first published. Glazer was already well on his way to debunking the myth of complete immigrant assimilation that he would soon demolish in Beyond the Melting Pot. His concern here is the relationship between American identity and ethnic consciousness over the course of American history and he shows that the charge of dual identity flung at successive waves of twentieth century immigrants is in fat a phenomenon stretching back through American history. If anything, Swedish and German immigrants of the mid-nineteenth century—with more fully formed national identities upon arrival—had a more powerful double identity than later Italians and Jews and Greeks, even seeking to carve out national homes on American soil. Paradoxically, it was the group experience of America that produced a greater ethnic national consciousness among Jews, Italians and Greeks.

These observations led Glazer to a far suppler grasp of the interplay between national identities than many of his generational peers on both the left and right. If dubious about its more extreme propositions, he was far more open—certainly less threatened by—multiculturalism during the great debates of the 1980s and 1990s. His book We are all Multiculturalists Now from 1997 and his opening essay in this book “American Epic: then and now” are thoughtful and wry meditations on the realities of fragmentation in American society in the late twentieth century.

On the one hand he clearly roots for a central American identity to hold the country’s vastness, its hyphenated population together. On the other, he recognizes how much race has disunited the country’s white and black citizens since its very inception, belying the myth of an Edenic, united America of the past. Glazer had little fear that Americanness was disintegrating simply because he understood that American identity had always been far more elastic, more ambiguous, more double-sided than those who wished to narrowly define it ever imagined. In one of the most recent essays in this volume, “Assimilation Today, Is One Identity Enough?” from 2004, Glazer muses on yet a further evolution of this process, the recent trend of dual citizenship, once unthinkable, that is now comfortably embraced by any number of Americans.

Glazer’s sojourn at Commentary in the fifties coincided with the height of the Cold War. Communism, a once parochial interest of Glazer and the New York intellectuals, became the central issue of American foreign policy. At the same time, America’s fear of a newly powerful Soviet Union was opportunistically manipulated into a domestic “red scare” by Senator Joseph McCarthy, the House Committee on UnAmerican Activities(HUAC) and countless other state and local officials across the country. Commentary rushed to the precarious center of a roiling national controversy.

Glazer and the New York intellectuals knew that the feckless American Communist Party never came close to posing this kind of existential threat. But they were also aware that the Party was wholly subordinate to the Soviet Union and a willing instrument of its foreign policy, not to mention an active recruiting ground for Soviet spies such as Alger Hiss and Julius Rosenberg. Intellectual pugilists from the streets of New York, the men and women around Commentary, who had long fought communists in intellectual circles, rose to the fight, focusing their ire on the wrong-headed defense of the Party by Left wing writers.

Many thought they ignored the plight of those many well-meaning men and women who had flocked to the party (or its many front group) as a champion of economic justice. It was Glazer’s self-assigned job to craft a devastating attack on the senator’s modus operandi, “The Method of Senator McCarthy.” Did Glazer do enough? Anyone who has studied the period knows it was an ethical malestrom. To this day, almost alone among the combatants of that era on either side, Glazer has not protected himself in later years with the armor of self-righteousness.

Did Glazer seek out political fights or did they find him? As the McCarthy era faded from view, Glazer got a job teaching at the University of California at Berkeley, just in time to confront the student protestors of the Free Speech Movement in 1964. Many of the young radicals, intensely political like himself, were his students or his former students and he could not help but sympathize with their initial fight against racial discrimination in the Bay Area or their plea for greater openness in the university. But when their demands grew as well as their fury against an essentially liberal and open university, he broke decisively with them.

Ultimately he saw in the New Left a utopianism, a fatal attraction for sweeping political theories of American society that discarded all the “messiness,” “the grubby ordinariness” he had come to embrace. The young members of the New Left were interested in heroic gestures; Glazer at middle age understood life’s uncorrectable ambiguities. He was accused of having grown too comfortable, too sedate, but these characteristics were hard to find in his own fierce defense of America’s—and the university’s—pluralistic values against denunciations of American democracy as merely a corporate sham.

In 1965, while Glazer was at Berkeley, his New York friends Irving Kristol and Daniel Bell hatched an idea for a new magazine they named The Public Interest, designed for an age of remarkable political consensus in Western political life. Marxism was a spent force. Liberalism dominated both the Republican and Democratic parties in America. “The end of ideology” had come, according to Bell and others. The new journal would replace ideology with social science knowledge in its exploration of public policy. If Glazer’s distance did not permit him to be a founder, he was one in all but name and would go on to be a co-editor of the magazine with Kristol for many years, after Bell left the journal.

The new magazine represented a sea change in New York intellectual sensibility, a revolution in what Glazer described as the group’s wholly “abstract relationship to politics” in its early years, especially American politics. The magazine’s creation was a mark of how far Glazer and Bell and Kristol had traveled since their youth. They had not only come to understand the American political scene, they now felt they were in a position to influence it—and influence it they did. The Public Interest was a landmark publication whose imprint was left not only on American public policy over four decades but on subsequent generations of intellectuals.

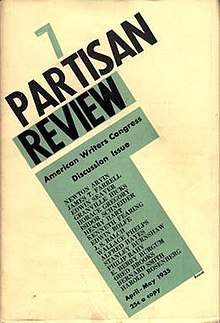

The Public Interest focused on the hard-headed realities of public policy, a seemingly less heady endeavor than that of the New York intellectuals’ earlier more literary magazines. Yet it approached policy with the erudition and flair reminiscent of Partisan Review.

To read Glazer’s Limits of Social Policy, (Commentary 1971), from the same period, one is reminded of how much has changed in our political life since then. It is a sober-minded and wholly original analysis of what he terms the “crisis in social policy”.

The crisis Glazer seeks to understand is the massive rise in the welfare rolls and the continuing break up of families, despite decades of liberal social policies. He takes us through a litany of plausible explanations—lack of jobs, poorly targeted payments to single mothers only, greater access to benefits for those previously denied—and one by one discards them as faulty or at best partial explanations for the problem. Glazer carefully marshals his data and takes a broad view, comparing the United States to more generous European welfare systems. He is neither hysterical nor incendiary nor dismissive. But he is disturbed.

He assails the midcentury liberal arrogance that all social problems can, in the end, be solved by government programs. More devastatingly, he argues that the very social policies designed to ameliorate social problems must inevitably create new ones. The authority of government professionals cannot help but further erode “traditional measures, traditional restraints, traditional organization.” The one-time radical has become a defender and admirer of tradition. Marx has given way to a touch of Burke. Liberal optimism to a more conservative caution. Or has it?