How China Sees World Order

Can Beijing be a 'responsible stakeholder'?

First, China often adopts a different set of approaches to institutions and rules that apply in Asia than it does on broader global issues. Closer to home, Beijing is more likely to oppose existing rules, as in the maritime and human-rights spheres. It is also more likely to advance alternative institutions inside of Asia than further afield, as with the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and Beijing’s One Belt, One Road initiative. At the same time, China demonstrates support and even a degree of leadership on several broader international issues.

Chinese activism on these issues does not amount to altruism, and Beijing has abiding national interests in supporting these regimes. As a result, U.S. policymakers should not convince themselves that they need to “buy” Chinese participation at the UN or on climate change by making compromises elsewhere in the bilateral relationship. It seems quite unlikely that Washington will be able to locate a particular set of concessions on regional issues that will guarantee Beijing’s support for a U.S.-Chinese “grand bargain.” Instead, a well-calibrated U.S. engagement strategy must acknowledge that China can contest regional rules while buttressing global ones, and will do so as its interests dictate.

Second, there is a difference between Chinese attempts to erode existing international rules (and America’s dominant role in setting them) and a move toward wholesale replacement. Even in the maritime order, which represents perhaps Beijing’s most visible transgressions, China often opts for ambiguity in its strategy, rather than attempting to advance new rules of its own. Beijing insists that Chinese behavior is consistent with the Law of the Sea, not that the law should be scrapped or modified. Similarly, China’s manifest violations of existing human-rights conventions, and its support for authoritarianism in general, in no way translate into a new Chinese-backed human-rights regime. Where China is not advancing replacement regimes, U.S. leaders should adopt strategies that unambiguously reaffirm and reinforce existing rules with the help of allies and partners. They must highlight Beijing’s rejectionist positions as anomalous and endeavor to limit their influence.

Third, as China and others offer concepts for alternative institutions, the United States should not adopt knee-jerk rejectionism itself. Here the Obama administration’s opposition to the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank is a case study in what not to do. The AIIB may have its flaws, but opposing the very existence of a source of capital for countries that need it is a fool’s errand. Instead, the United States should focus its efforts on encouraging transparency in the bank’s governance and raising its lending standards.

New regimes and organizations do not automatically lead to the erosion of the prevailing order; the specific rules in question and the organization’s intent make all the difference. American support or opposition should be calibrated accordingly. In some cases, as with the AIIB, a China leading a new and rules-bound multilateral organization is precisely what the United States should want to see, if the governance and standards are right. Similarly, it remains to be seen how China will try to implement its One Belt, One Road initiative, but the project may develop infrastructure in Central Asia in ways that actually complement U.S. interests.

Fourth, U.S. policymakers should recognize that given the significant challenges in pushing back against China when it thwarts existing rules and shaping its efforts to build new institutions, U.S.-Chinese relations are bound to be especially competitive in those domains where rules remain unwritten. In areas such as cybersecurity and outer space, Washington should be particularly vigorous in crafting new governance structures and employing a diplomatic effort to win support for them. It should invite China’s support and voice in making the rules but enlist others in pushing back against any attempts by Beijing to use its voice to undermine the principles that should animate them. To that end, the difference between rule breaking and compliance in these new areas should be as clear as possible, as soon as possible.

Finally, while China’s leaders appear to be engaged in a complex international-engagement strategy, it is possible that they themselves do not know what that approach will look like in the future. Beijing may ultimately choose to sign on to emerging Internet-governance rules, or abandon some of its regional economic initiatives if its economic turbulence continues. In light of this uncertainty, an appropriately nimble U.S. policy must incorporate the reality that China’s engagement strategy in different domains may change as future events dictate.

IN A recent interview, President Obama summed up the fundamental thesis underlying China policy under successive administrations. “If we get [the relationship] right and China continues on a peaceful rise,” he said, “we have a partner that is growing in capability and sharing with us the burdens and responsibilities of maintaining an international order.” The converse, however, is deeply unattractive. If China fails, or “if it feels so overwhelmed that it never takes on the responsibilities of a country its size in maintaining the international order,” the chances of dealing with global challenges will decline and the possibility of conflict rise.

In this last year of Obama’s second term, the 2016 U.S. presidential election is taking place amid broad questions of China’s future—not only what kind of power it seeks to be but also the degree to which Beijing, facing sliding economic growth and rising defense investments, can make good on its aspirations.

The presidential candidates also face questions of international order that are more fundamental than any since the end of the Cold War. Long gone are concerns about an American hyperpower writing the world’s rules and ignoring them wherever it wishes. Instead, the fraying order has moved into the front of foreign-policy minds, as has America’s limited power to shape and enforce its terms. The candidates and their advisors will need to offer strategies to bolster world order, to reshape it where necessary and to ensure that it has a fighting chance of living on for at least another seven decades.

Effective and enduring U.S. global leadership requires that policymakers accept a new normal in the relationship with China. China will cooperate in some areas and compete in others. The next American administration will need to simultaneously work with China on climate change, shape Beijing’s emerging economic institutions, and stand tough on cyber security and the South China Sea. It will also need to work closely with its pantheon of allies and partners, many of whom not only have a stake in the endurance of international order but also have for years been its pillars.

This attempt, and the imperative of working with traditional friends to shape Beijing’s choices, starts with an appreciation for the realities of global order today, and of China’s multifaceted approach to it. With extension of that order the chief aim of American grand strategy, getting China right—or at least as right as possible—is critical to the effort.

Richard Fontaine is the president of the Center for a New American Security. Mira Rapp-Hooper is a senior fellow in Asia-Pacific Security at the Center for a New American Security.

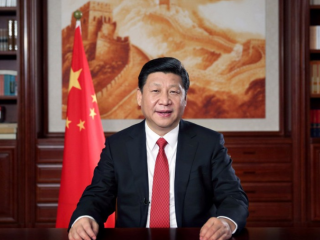

Image: Wikimedia Commons/@Hye900711