How Duterte Turned the Philippines Into China's New Play Thing

Rodrigo Duterte, in pursuit of development dollars, has put his country's national security in jeopardy. In fact, Duterte's first major foreign policy decision, barely a month into office, was to effectively dump the Philippines’ historic legal warfare victory against China.

Contemplating on the geopolitical earthquake of the twentieth century, namely the collapse of the once-mighty Soviet Empire, Francis Fukuyama emphasized the necessity for distinguishing between 'what is essential and what is contingent or accidental in world history'. Drawing on the works of G. W .F. Hegel (via Alexandre Kojève) and Plato, Fukuyama foresaw the twenty-first century as the age of Western triumphalism, a unique era marked by the world’s post-ideological embrace of democratic capitalism as the only game in town.

Inspired by the works of Friedrich Nietzsche, he came to worry less about a return to the great power rivalries of modern times than nihilistic slide boredom and existential anomie. Hence, ‘the last man’ part of the book-length version of Fukuyama’s groundbreaking essay at the National Interest. Three decades since the publication of The End of History (1989), another geopolitical earthquake has shaken the world, though, so far, on a far smaller scale.

This month, Philippine president Rodrigo Duterte effectively ended his country’s century-old alliance with the United States. By unilaterally abrogating the 1999 Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA), which provided the legal framework for entry and rotational stationing of American troops on Philippine soil, the Filipino leader has made robust bilateral security cooperation close to impossible The Philippine-U.S. Mutual Defense Treaty (MDT), which was forged on the ruins of Second World War, stand like an empty shell, a CPU without an operating system. The VFA was the software, which operationalized the MDT.

On paper, the alliance still stands but, in the words of a top Filipino official, it’s now “practically useless.” The perfunctory and highly dramatic abrogation of the VFA was deeply personal, brazenly politicized, and, frankly, a reckless decision, which will expose the Philippines to a whole host of security challenges, including the menace of transnational terrorism and extreme weather conditions that have ravaged the country in recent years. And no less than China—namely, the only power that has provided a real ideological alternative to Fukuyama’s triumphant democratic capitalism—is expected to be the biggest winner of Duterte’s latest gambit.

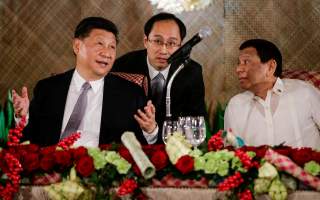

Quid Pro Quo with China

As shocking as Duterte’s latest decision seems, it’s far from surprising. I vividly recall the final stretch of 2016 presidential elections in the Philippines, when the former mayor of Davao transformed from a dark horse into the undisputed frontrunner. Suddenly, his speeches, often laced with colorful adjectives and shameless chutzpah, gained unprecedented significance, now worthy of deliberate and meticulous analysis.

As far as foreign policy is concerned, two of Duterte’s public speeches stood out for me. The first one was in Palawan, the Philippines’ westernmost island embracing the disputed waters of the South China Sea and the prized Spratly islands. The speech is particularly relevant, because almost the entire world focused on its least serious portion, specifically when Duterte quipped about taking a “Jetski” and his willingness to “carry a flag” to the Spratlys to summon the Chinese for a “fist fight or gun fight” if necessary to defend the Philippines’ claims in the area.

A careful look at the entire speech, however, reveals a disturbing tendency, namely Duterte’s inexplicable deference, if not outright acquiescence, to China in complete public spotlight. Without a touch of irony or any attempt at qualifying his statement, the former Davao mayor made it clear, addressing China, “[If you] build me a train around Mindanao, build me train from Manila to Bicol . . . build me a train going to Batangas, for the six years that I’ll be president, I’ll shut up [on the South China Sea disputes].”

The second one was even more interesting since we were both in the same news package. In it, China’s premier global channel, CCTV (later renamed to CGTN), interviewed the then two leading presidential candidates, Filipina Sen. Grace Poe-Llamanzares and Duterte. There, one can see a completely different Duterte: He is unrecognizably statesmanlike, impressively coherent, and highly respectful towards China (once in power, he acted broadly in a similar vein during numerous officials trips to China). The soon-to-be-president brazenly echoed his quid pro quo: “What I need from China is help to develop my country.” In exchange, he would downgrade security cooperation with the United States and, crucially, disregard the Philippines’ landmark arbitration award against China in the South China Sea.

As the Chinese narrator in the news package confidently puts it, “[Duterte] says he would not count on the Americans coming to the Philippines’ rescue and would have even considered dropping an arbitration case the Aquino administration filed against China.” In fairness, Duterte was broadly transparent with his geopolitical vision, yet few took him either seriously or literally at home. He won by a historic landslide, handily defeating his two leading American-trained rivals, namely Interior Secretary Manuel Roxas (Wharton) and Senator Grace Poe (Boston College), who similarly favored robust ties with the United States to check Chinese expansionism.

Follow the Leader

Guess what? Once in power, Duterte did exactly what he promised in the Chinese news package. His first major foreign policy decision, barely a month into office, was to effectively dump the Philippines’ historic legal warfare victory against China. The Filipino president nonchalantly announced that he will “set aside” the arbitral tribunal ruling at The Hague, which rejected the bulk of Beijing’s expansive claims in adjacent waters, in the interest of developing warmer ties with China.

Meanwhile, during his first major overseas visits, beginning with China, Duterte was even more blunt about his take on the Philippine-U.S. alliance: “I want, maybe in the next two years, my country free of the presence of foreign military troops. I want them [Americans] out.” Halfway into his six-year term in office, Duterte has effectively fulfilled his earlier threat. Initially, the news of the VFA’s abrogation was met with skepticism, many wondering if the president is willing to risk alienating the Philippine defense establishment and the broader Filipino public, which prizes the country’s century-old alliance with the United States.

After all, many of the Philippines’ leading officers, as well as several presidents, were trained by Americans throughout decades of crosscutting defense cooperation. During the Cold War, the Philippines hosted America’s biggest overseas bases in Subic and Clark. Only a few years ago, America was more popular among Filipinos than among Americans themselves. Today, it is still the Philippines’ most preferred foreign partner. In contrast, China’s net approval ratings have been consistently in the negative territory, reaching a new low (-33 percent) last year amid festering disputes in the South China Sea and the influx of illicit Chinese investments into the Philippines.

Though the Philippine-U.S. alliance has been far from perfect, the Pentagon has been a source of critical assistance to the Southeast Asian country throughout the post–Cold War period. The VFA has facilitated almost $2 billion in assistance to the Philippines, an amount that is not much compared to what non-democratic non-allied countries such as Pakistan and Egypt have been receiving in recent decades. Nonetheless, the quality of American assistance has been decisive, especially in the realm of nontraditional security cooperation.

Most notably, the United States was extremely helpful in humanitarian assistance and disaster relief operations, including the deployment of an aircraft carrier, sixty-six aircraft, and as many as 13,400 soldiers during the Haiyan superstorm, which devastated much of central Philippines in 2013. And more recently, the United States provided much-needed Special Forces training, high-grade weaponry, and real-time intelligence and surveillance operations during the months-long siege of Marawi by Islamic militants.

Moreover, the Trump administration has also stepped up maritime security assistance to the Philippines, including through increased defense aid, more unambiguous assurances of assistance in the South China Sea, and consistent upgrades to the Philippine Coast Guard and surveillance capabilities. Surely, there was still a huge room for improvement. But bilateral relations took a nosedive following the Filipino president’s threat to sever security cooperation in response to reported United States’ travel ban against top Filipino officials over human rights concerns, especially former police chief and longtime Duterte ally, Ronald dela Rosa.

It’s likely that Duterte hoped to cajole the United States into rolling back effective and incoming sanctions against his inner circle by leveraging the VFA. But President Donald Trump made it clear that he is “fine” with ending the agreement if this meant saving “a lot of money” for America. It’s a dramatic turnaround for the two allies, which conducted close to three-hundred joint military activities last year, the most among America’s partners in the Indo-Pacific region. Now all of a sudden, at least half of scheduled 318 joint military activities this year are in jeopardy. Bilateral exercises could collapse to zero in Duterte’s twilight years in office. Now, there are even discussions of a potential Philippine VFA with Russia and China, the United States’ chief rivals. (One can’t also rule out the possibility for a last-minute plot twist, as adults in both administrations desperately seek to rescue the century-old alliance.) There goes another reason to doubt “The end of history” thesis in our century of political befuddlement, ideological promiscuity, and breakneck unpredictability.