Why Sun Tzu Isn't Working for China Anymore

China's ruling party is beginning to encounter an international backlash against its methods and increasing discontent with its authoritarian ways.

What does an insecure authoritarian regime do when it believes it is being undermined from within and encircled from without by its most potent foe, and threatened with extinction? For the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in the early 1990s, convinced that the planet’s sole superpower was out to get it, the reflex was to turn for guidance to the Warring States period of Chinese history.

The Warring States period (fifth century to 221 BC) saw China’s first great flourishing of written culture and ideas, along with rapid technological progress and burgeoning material wealth, all amid a frenzy of interstate competition and conquest. It was when the foundations of the modern Chinese state were laid: China’s first centralized, authoritarian, densely populated land empire was forged on the scorched ruins of the warring states. And it was the period when the region’s deep strategic template for geopolitical competition was laid down, a template which persists to the present day.

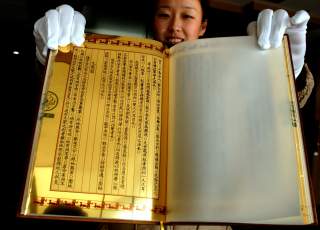

The trauma of those times, and its lesson for combative rulers and generals ever since, was captured in the first line of the treatise attributed to Sun Tzu, the best-known strategist of the era: “War is the defining function of the state.” In effect, Sun Tzu declared that to be a state was to be at war. Everything else you needed to know about running a state or leading an army in his day, followed from that assertion. And since you are always at war, the ploys and deceptions of warfare—inimical though they are to interstate trust and cooperation—are always at play, regardless whether or when conflict escalates to the point of a physical battle. It was a radically realist position, and it became the geostrategic paradigm of the period.

An Insecure Party

The CCP has not always been in a state of real or virtual war since it was formed and in the early 1990s, it found itself plunged into existential crisis following upheavals on the home front exacerbated by a burst of international ostracism. For the Party elite, a wave of nationwide protests in 1989 had been a near-death experience. Those protests were fueled by anger about official corruption, tied with demands for democratic accountability. The CCP’s elderly leaders, spooked by what they feared were the stirrings of a revolt, sent in the tanks. Unarmed citizens were massacred by the hundreds, most notoriously on the approaches to Tiananmen Square in Beijing.

Two years later those same leaders watched as the communist-ruled Soviet Union imploded, apparently weakened from within by Western values and pressured from outside by the forces of economic globalization. For the Party’s perspective, all signs seemed to point to the United States, then at the zenith of its global power and influence, as the main threat to continued CCP rule.

Viewed through the CCP’s default Warring-States lens, America was clearly a “hegemon,” the global capo dei capi, and in the Warring States paradigm, a hegemon cannot rest until it has neutralized all rivals. The Party’s reflex response was to invoke a time-honored approach of embattled sovereigns from the Warring States period: make nice with the top dog while patiently accruing strategic advantage, ready to turn the tables at some future phase in the conflict.

The foundation of this approach, expressed by Deng Xiaoping in a confidential speech to China’s senior diplomats and generals in 1991, was tao guang yang hui (韬光养晦)—to “shroud brightness and cultivate obscurity.” In other words: proceed discreetly in international affairs, taking care not to draw attention to the Party’s long-term ambitions. In particular, the CCP’s ambition to reset the global hierarchy in China’s favor by outstripping the old hegemon.

Three Strategic Programs

With tao guang yang hui as its guiding principle, and under the influence of Sun Tzu and other thinkers of the Warring States period, the Party instituted three strategic programs for advancing towards its ambitions.

The first of those programs entailed massively expanding the economy by inserting China at the heart of the global trade, rewarding the Chinese public for their patience with the regime while quickly filled the national coffers.

The second involved pouring funds into the People’s Liberation Army, converting it from a poorly equipped, infantry-centric institution into a force befitting a twenty-first-century superpower, focused on maritime-power projection and with a full complement of stealth, space and cyber capabilities.

The third program, designed to shield China against Western influence in an age of globalization and instant intercontinental communications, was an open-ended campaign of “Patriotic Education,” in which the Party-controlled domains of academia, news media, and the entertainment industry were enlisted to inoculate China’s youth with a strain of virulent nationalism.

Each of the three programs has, on the face of it, been a runaway success.

China is now far richer and stronger than it was a quarter of a century ago. Its young people know a great deal about the Nanjing massacre in 1937, but nothing about the Beijing massacre in 1989. The regime has significantly enhanced its strategic position and appears to be more firmly in control of China than ever. And it has achieved all this under the oversight of the country it designates as its chief adversary. The Warring States approach has delivered—so far.

However, the world has moved on and conditions have changed within China in ways that Warring States militarists had no reason to anticipate. The Party is beginning to encounter an international backlash against its strategy and methods, at the same time as it faces rising discontent with its authoritarian ways at home. Once again, the Party’s domestic legitimacy is at stake. The downsides of the Warring States paradigm are beginning to outweigh the benefits.

Burgeoning Backlash

China’s accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 2001, with all the compromises and commitments that membership entailed, was welcomed overseas as a milestone in the country’s journey towards convergence with international norms. But the view was very different from within the walls of Zhongnanhai, the vast CCP headquarters in the middle of Beijing. The United States had only recently bombed the Chinese embassy in Belgrade (the CCP leadership were convinced the attack was deliberate), and in 2000 the presidential election in Taiwan had been won by a radically pro-independence candidate—further evidence from the CCP perspective that democracy in Taiwan was part of a long-term U.S. plot to undermine and destroy the Party.

For the CCP, therefore, joining the WTO was not about convergence with the West. It was instead a milestone in the Party’s decades-long campaign to redress the degrading imbalance in “comprehensive national power” between China and America, and a strategic maneuver targeting the soft underbelly of U.S. high technology exports and hyper-consumption. China was open to world trade, but the CCP never had any intention of welcoming in the notionally Western values that underpin the international rules-based order.

Now that enough Americans feel that China has been gaming the rules at their expense, the United States has begun reconfiguring its own rules for doing business with China. The trade war is the opening salvo in a campaign which significantly alters the calculus for China’s mercantilist, export-dependent economic model. Additionally, the ensuing disruption potentially undermines a central plank of the party’s legitimacy.

Moreover, China's military ambitions along its maritime periphery can no longer be disguised. For years Beijing has stated, in international forums, that its programs for building bases in the South China Sea, claims in the East China Sea, and power projection into the Western Pacific are an innocuous adjunct to the country's "peaceful rise." The narrative for domestic audiences in China, however, has been somewhat darker—a promise to monopolize marine resources for the homeland, to repel the "aggressive" presence of America in the region, and to wrest the strategically important East China Sea islets from Japanese control. Above all, the mission has been—and remains—to encircle and ultimately annex Taiwan, holding the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command at bay for long enough to create a fait accompli.

Alarmed by China's increasingly predatory posture, the countries of the region have discovered and begun cementing their common interest in working together for security and stability. States as diverse as Vietnam, Japan, Australia, and India have entered into strategic partnerships to counter intimidation by China. The United States too has rediscovered its strategic interest in countering China's disruption and asserting itself in the region. Every status-quo-altering military move that the CCP makes along its maritime periphery is now scrutinized and answered by America and its allies, in the light of China's quarter-century-long strategy of exploiting U.S. inattention.

Western countries have also become aware of the covert, organized nature of the CCP’s nationalistically driven campaign to influence and interfere with their policies that relate to China’s interests. The overseas operations of Beijing’s heavily funded United Front Work Department—boosted by “patriotic” students and indirectly aided by enablers in Western academia, think tanks and the media—are now increasingly recognized and called out in the countries that those operations target. Another cat is out of the bag.

In sum, the Warring-States reliance on stealth and misdirection has run its course. What lies ahead, if China continues along its adversarial tack, is likely to be more Clausewitz than Sun Tzu.