Why the Surrender of Imperial Japan Still Matters

Harry Truman’s decision to drop bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki cannot be judged by modern-day nuclear war concerns.

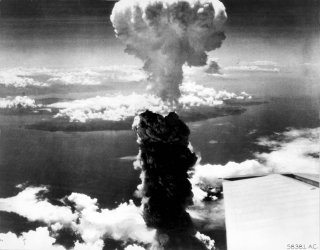

Wednesday will be the seventy-fifty anniversary of Imperial Japan’s formal surrender, thus ending the year’s annual debates over the tragedies preceding President Harry Truman’s decision to use nuclear weapons on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The tragic lessons tied to these events remain central to peace and stability in the world.

This year, Prime Minister Shinzo Abe decided to send one of the largest cabinet delegations in recent history to the controversial Yasukuni Shrine for Japan’s war dead. This annual event, which coincides with the anniversary, was punctuated by his official statement, which quickly displeased most of Asia, evoking strong denunciations by China and South Korea.

In his statement, Abe resurrected the morally flawed and historically dishonest “Japan as victim” trope by focusing in detail on Japan’s pain, but no one else’s pain, with no mention of why the war happened and who was responsible for it. This, unfortunately, ignored the heart of his well-received remarks to a Joint Session of Congress in 2015.

More significantly, his statement went against today’s broad consensus in Japan that the Imperial government bore some responsibility for the war, what the war engendered, and what might be described as “militant pacificism.” In practice, this consistently restrains Abe’s goal of a more militant national defense posture and weaponry. While understandable, the traumas of 1945 underwrite Japan’s reluctance to assume the full responsibilities of a modern military power despite growing regional challenges.

Visits to the Yasunkuni Shrine have long endured criticism due to its enshrined convicted war criminals, which is why the Emperor Naruhito has refused to visit it. This year’s remembrances of the war have prompted an outpouring of thoughtful discussions of the key questions still resonating in policy debates today: why did Truman decide to be the first—and so far only—national leader to use nuclear weapons and how should history judge him as multiple nations seek to ensure that there is never again a nuclear attack.

Truman’s controversial decision to use nuclear weapons has often been questioned, which isn’t just about historic judgments and moral considerations. Those questions center around geostrategic policy concerns given the rising tensions between the United States and its major nuclear weapons rivals, Russia and China. They also center around the long-time threats of North Korea, consistent squabbles between India and Pakistan, the Trump administration’s various attacks on all U.S. alliances, and the currently imperiled arms control agreements which also have helped maintain peace.

That’s why it’s really important to be careful about using history in broad, essentially moralistic ways, but especially when past events are contorted by political leaders seeking to reshape “history” to their own ends. One clear lesson of history still playing out in both Europe and Asia: nationalism as state policy is a cancer that has often proven to be fatal.

Since the dawn of the nuclear age, arguments against any use of nuclear weapons, however well-intentioned, underscore the risks of projecting back new information and current values that persistently ignore context such as the Howard Baker classic “what did they know and when did they know it.”

Today, it’s impossible for any of us to escape the “nuclear terror” of the Cold War years. But Truman and his associates couldn’t possibly have felt any of that, especially after all that they had seen and all that the American people endured. Their “context” unavoidably included years of mass civilian bombings throughout Europe and Asia, carried out by every country involved, including Imperial Japan.

In 1945, despite the Potsdam Conference’s discussion over the Emperor’s fate, virulent Imperial Military opposition to the peace feelers being offered via Moscow stalemated the small, if highly-placed “peace faction.” So when totaling up the horrifying human cost of the possible impact of nuclear weapons on Joseph Stalin’s machinations, critics must examine whether a surrender delay would have produced what happened next in Germany. Would we today have a North Japan and South Japan akin to the ongoing North Korea and South Korea tragedy?

Giving credibility to Stalin’s contemplated involvement springs the trap of ignoring other, all-too-plausible outcomes, such as the possibility that there would be no quick surrender, that the mass starvation Japan already had endured would be further exacerbated, that deaths would have approached genocidal levels if the Imperial Generals had carried out their intent to fight to the last schoolchild.

Impelled by our own, modern-day anxieties, we’re often left with a moral lecture that touches base with a terrible war in which the aggressors, such as Imperial Japan and Nazi Germany, did unspeakable things. Yet many critics now seem more interested in denouncing Truman and colleagues based on value-laden assertions grounded in our very real nuclear anxieties.

Factual misstatements remain an obstacle to accurate assessment. Secretary of State Henry L. Stimson’s “one million U.S. casualties” projection is often presented as an after-the-fact rationalization, rather than associated with its origin: the then-current facts about Iwo Jima, Okinawa, et al on both Japanese and U.S. casualties, which are the very rock of the foundation for Stimson’s argument, and Truman’s duty to consider.

Recently, some critics have tried to argue that Truman was wrong not to risk U.S. lives in order to save Japanese civilians from the nuclear holocaust, even though the context for the bombings encompassed the multiple-millions of civilian dead world-wide and a rising awareness of the Holocaust.

After all, the horrific Allied bombings of Germany and Japan failed to bring the then-projected benefits, but the Strategic Bombing Survey didn’t exist until well after the war and can’t be projected back in time.

Similarly, the world correctly now condemns civilian bombings from Kosovo to Syria, and it is true that U.S. military lives have been lost in Afghanistan and Iraq in an effort to avoid incurring civilian casualties. But again, critics cannot project the present back to 1945. As Truman once said in a run-up debate, with over four hundred thousand dead already, how can I tell another American family their loved one died to protect a Japanese?

Finally, speaking from a cultural perspective, even if we ignore the Bible’s litany of revenge, we can’t ignore the moral dilemma of, for lack of a better way to put it, “societal guilt.” Are critics prepared to argue that the Soviet Army shouldn’t have pressed on to Berlin because so many German civilians were killed and raped before the surrender? The average German we now know had a lot to do with the Holocaust. And have you ever talked to a Russian about how many family members are buried outside Stalingrad? Have you ever spoken to the Chinese, Koreans, Southeast Asians, Filipino, Australian families about their horrific treatment and losses at the hands of Imperial Japan?

Among the traps or risks in not doing so is to justify claims the War Crimes Trials were “victor’s justice,” the explicit theme of the museum at Yakusuni. And most reprehensibly, it underwrites the inexcusable “poor Japan as victim” trope implicit in Abe’s recent remarks.

Despite that, there is now broad acceptance in Japan that of course actions have consequences, and that the weight of history is not easily lifted, hence the agonizing heart of Abe’s statement. A current American example: The “Black Lives Matter” movement is forcing the country to deal with the blood-drenched history of racism and the moral and political price it has yet to fully pay.

If it’s true that the moral arc of history bends toward justice, then its definition of war is likely to be harsh. Abraham Lincoln put it best in his second inaugural address:

“If we shall suppose that American Slavery is one of those offences which, in the providence of God [means war] must needs come . . . [and] if God wills that it continue, until all the wealth piled by the bond-man’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk, and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash, shall be paid by another drawn with the sword, as was said three thousand years ago, so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord, are true and righteous altogether."

Whether or not a person can accept Hiroshima, Nagasaki, or the Russian rape of Germany, as the “harsh arc of justice,” in looking back on 1945 they owe it to themselves and the dead to accurately and honestly discuss why it happened, not just how truly awful it was. That is the only way that we, as a society, can ever hope to achieve “never again.”

Christopher Nelson recently retired from a long career as a journalist and Asia policy analyst, including The Nelson Report. He has written two books on the American Civil War.

Image: Reuters