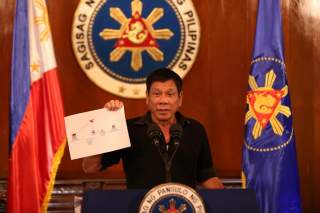

Will Duterte Really Abandon the U.S. for China?

Disagreements over Duterte's "war on drugs" stand at the heart of a deepening rift, which threatens to upend Washington's relations with its oldest Asian ally.

The year 2016 has been a watershed for Philippine-American relations, in particular, and, in broader terms, for the Sino-American showdown in the South China Sea. At the center of this geopolitical hiccup is no less than the Philippines’ controversial and tough-talking leader Rodrigo Duterte, who has repeatedly threatened to end his country’s century-old military alliance with America. Disagreements over Duterte’s “war on drugs” stand at the heart of a deepening rift, which threatens to upend Washington’s relations with its oldest Asian ally.

Through a cocktail of insults, threats and long-winding tirades, Duterte has underscored his uncompromising policy against the proliferation of illegal drugs. When Washington threatened to nix the $433 million Millennium Challenge Corporation aid package due to “concerns around rule of law and civil liberties in the Philippines" the Filipino leader simply shrugged it off, claiming his country “will not go hungry without the American aid. We are not that desperate.” To up the ante, Duterte claimed that China is more than willing to fill in the aid vacuum. It is precisely this growing reliance on the “China card” that has begun to reshape the geopolitical landscape in the region, particularly in the South China Sea.

Much to the consternation of the security-media-intelligentsia establishment in the Philippines, Duterte has openly declared that in the “play of politics now, I will set aside the arbitral ruling.” That statement marked the culmination of a months-long strategic flirtation between Manila and Beijing since the inauguration of Duterte in June 30. For at least three years, the Philippines, under the Benigno Aquino administration, stood as China’s bitterest rival in the South China Sea. It spearheaded a landmark arbitration case, which promised to mobilize the international community against China’s brazen disregard for international law and the rights of smaller neighboring states in adjacent waters.

With Duterte at the helm, the Philippines immediately made a de facto volte-face, downplaying the arbitration case, portraying it as a mere bilateral issue, and opted for dialogue and engagement rather than confrontation with China. Almost singlehandedly, Duterte has made a mockery of the Obama administration’s Pivot to Asia (P2A) strategy, which has heavily relied on the cooperation of regional allies against China. At some point, Washington worried about a potential “Duterte wave” of defections among regional allies, as Malaysia doubled down on its overtures towards the Middle Kingdom. The equally surprising election of Donald Trump, however, has injected a new dynamic into the picture. Around the region, Trump’s ascent is expected to be accompanied by a more muscular and robust pushback against Chinese maritime assertiveness. In Manila, there is great expectation that relations will improve under the incoming American administration.

The October Surprise

A year earlier, hardly anyone foresaw how consequential Duterte’s election could be in terms of Philippine foreign and regional territorial disputes. In fact, at the beginning, none of the leading Philippine pundits took Duterte’s bid for the presidency any more seriously than American pundits took Trump’s. He was largely dismissed as an uncouth provincial mayor, a “political outsider” devoid of sufficient funds and machinery, and an absolute amateur in national and international affairs. However, Dutetre’s promise of “real change” however was more than empty talk.

His tough rhetoric against illegal drugs and criminal syndicates mobilized the law enforcement agencies even before he officially assumed power. He promised a bloody all-out war, and this is precisely what has happened in recent months. For those who carefully followed his statements and their policy implications during the campaign period, Duterte actually also promised a shift in Philippine foreign policy. As early as February, when he was still struggling in the surveys, Duterte vowed to reset the Philippines’ China policy, particularly vis-à-vis the South China Sea disputes. The firebrand Filipino leader effectively declared that he would be willing to set aside Philippine claims in the area in exchange for improved relations with and massive infrastructure investments from China. Yet barely any major ally, including America, seemed to take those statements seriously. In fact, at the beginning, many failed to take Duterte seriously and literally, when he was being both serious and literal. The writing was on the wall, but few bothered to notice it.

In October, barely hundred days into office, Duterte was in Beijing, promising a “separation” from America, joining China’s “ideological flow” and relegating the arbitration case to the dustbin of history. Meanwhile, the Obama administration ramped up its criticism of Duterte’s human rights record. Other key Western allies such as the European Union as well as the United Nations joined. Confident about China’s backing, the Filipino leader brandished his middle finger and deployed a torrent of insults against top American leaders. By the end of the year, the Philippines and China openly negotiated the contours of a long-term military agreement just as Duterte downgraded military cooperation with America.

Into the Abyss

As I predicted in my earlier works, Duterte is unlikely to scrap the century-old alliance with America altogether, but he could downgrade certain aspects of bilateral military cooperation in exchange for improved ties with China. Latest reports suggest there would be no joint US-Philippine patrols in the South China Sea. Major joint military exercises such as the Philippine Amphibious Landing Exercise (Phiblex) and Cooperation Afloat Readiness and Training Exercise (Carat) were reportedly axed. The fate of the massive Balikatan (shoulder-to-shoulder) joint exercises is now in limbo.

As I predicted in earlier lectures, differences over human rights issues could severely embitter bilateral relations between the Duterte and Obama administrations. Massive American aid to the Philippines as well as shipment of American equipment and guns to the Philippine national police are now on hold. Duterte’s leading critic, Senator Leila De Lima, was warmly welcomed in Washington, where she received the prestigious 100 Global Thinkers award by Foreign Policy magazine. Bilateral relations are arguably at their lowest point in history. The election of Trump, however, holds the promise of restoring the frayed alliance.

On multiple occasions, Duterte couldn’t hide his excitement over the election of Trump. Since the shocking victory of Trump in November, Duterte has said largely positive things about his incoming American counterpart, reserving his venomous insults for the outgoing Obama administration. Recently, Duterte even admitted to have rooted for Trump in the American elections. “I will let Obama fade away and if he disappears, then I will begin to reassess [our bilateral relations],” Duterte said during his latest tirades against the outgoing American president. “I like [Trump’s] mouth, it’s like mine…we’re similar. And you know, people with the same feather flock together.”

At least three factors inform Duterte’s optimism vis-à-vis Trump. First and foremost, the Duterte administration expects Obama’s successor to be a brutal pragmatist who will put strategic interests ahead of human rights and democracy concerns. Not to mention, after his surprisingly cordial phone conversation with Trump, an enamored Duterte controversially claimed that his incoming American counterpart even supports his war on drugs.

Moreover, Duterte expects America to adopt a more robust, unilateralist approach to the South China Sea disputes. Unlike the Obama administration, which placed pressure on allies such as the Philippines to shoulder the cost of constraining China’s maritime assertiveness, Trump is expected to launch a Reagan-style “peace through strength” policy.

In Duterte’s estimation, this means the Philippines can stay out of the South China Sea disputes and leave the two superpowers to slug it out in the high seas. This would, theoretically, allow him to keep an equi-proximate relationship with both powers while maintaining Manila’s room for maneuver. For Duterte, the Philippines should stay out of the clash of titans and just nurse its own narrow national interest.

Duterte is also optimistic that his envoy to Washington, who is the owner of the Trump Tower in Manila, could leverage long-standing business relations. After all, the Trump family has been quite brazenly mixing business and politics in recent months. Not to mention that Sung Kim, Washington’s new ambassador to Manila and a former North Korea talks negotiator, seem well-equipped to deal with prickly Asian allies.

It goes without saying that predicting the future policy of highly mercurial leaders such as Duterte or Trump individually is probably a fool’s errand. Predicting their likely dynamic together is even a riskier affair. For now, however, Manila is optimistic that Obama’s successor could set aside recent dust ups in bilateral relations in favor of a new era of more pragmatic and muscular American leadership in Asia.

Richard Javad Heydarian is an Assistant Professor in international affairs and political science at De La Salle University, and previously served as a policy advisor at the Philippine House of Representatives. As a specialist on Asian geopolitics and economic affairs, he has written for or interviewed by Al Jazeera, Asia Times, BBC, Bloomberg, Foreign Affairs, The New York Times, Wall Street Journal, The Huffington Post, The Diplomat, The Financial Times, and USA TODAY, among other leading international publications. He is the author of How Capitalism Failed the Arab World: The Economic Roots and Precarious Future of the Middle East Uprisings (Zed, London), and the forthcoming book Asia’s New Battlefield: US, China, and the Struggle for Western Pacific (Zed, 2015). You can follow him on Twitter: @Richeydarian.