How the ‘Global War on Terror’ Failed Afghanistan

The Global War on Terror has failed; but failure, they say, is a better teacher than success, and if the United States can learn from this failure and how it was generated, it may be able to avoid more disasters in future.

We can’t say that we were not warned. In January 2002, at the start of the U.S. intervention in Afghanistan, British historian and former soldier Sir Michael Howard published an essay in Foreign Affairs titled, “What’s In A Name? How to Fight Terrorism.” In it, he warned that defining the U.S. response to 9/11 as a “Global War on Terror” (GWOT) would shape U.S. policies in profoundly negative ways. As he wrote,

[T]o use, or rather to misuse, the term “war” is not simply a matter of legality or pedantic semantics. It has deeper and more dangerous consequences. To declare that one is at war is immediately to create a war psychosis that may be totally counterproductive for the objective being sought.

Like others, Howard pinpointed the risk that declaring war on such a nebulous enemy as “terror” would make that war unending; that war would only drive populations into support for the terrorists and create a “with us or against us” attitude that would make it impossible to win over people from the other side; and that the longer wars continued the greater these tendencies would become.

He argued instead for the use of intelligence actions, diplomatic pressure, and limited force (of the kind that eventually killed Osama bin Laden and persuaded Pakistani intelligence to help in the capture of other Al Qaeda leaders). The wisdom of Howard’s words has been amply demonstrated by the disastrous outcomes of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Today, Howard’s allocutions about the GWOT should also be placed in a wider context of U.S. foreign and security policy in the past and future: the creation of “meta-narratives,” all-encompassing frameworks of thought and analysis into which a wide range of quite different issues are fitted. These narratives are focused on one supposedly monolithic, universal, and overwhelmingly powerful enemy, which it is necessary to confront everywhere. They are fed by American exceptionalist nationalism, with its conviction of America’s duty to lead the world to the inevitable triumph of democracy.

This enemy is cast not only as a military and ideological adversary but a force of evil, with the United States of America representing not only freedom and democracy, but good itself. This is how most Americans understood the Cold War; and amid the rain of condemnation that is falling on President Joe Biden over Afghanistan, it is vital to remember that not just the disaster of Iraq, but that of Afghanistan too, had their origins in how the George W. Bush administration turned the pursuit of the small terrorist group actually responsible for 9/11 into a global struggle for freedom and against “evil.”

In the case of Afghanistan, this led to the refusal to negotiate with the “terrorist” Taliban either before or after their initial defeat, and the U.S. commitment to democratic nation-building in one of the most inhospitable countries on Earth for such an effort. The GWOT was, however, a bipartisan delusion. A Democratic senator told me in 2002 that the United States should “turn Afghanistan into a beachhead of democracy and progress in the Muslim world.” It goes without saying that her knowledge of the terrain of this beachhead was precisely nil.

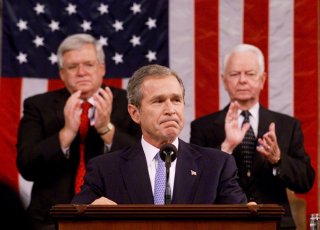

Key passages of Bush’s speech to Congress on September 20, 2001, read as follows:

…they [the Islamist extremists] follow in the path of fascism, and Nazism, and totalitarianism … How will we fight and win this war? We will direct every resource at our command — every means of diplomacy, every tool of intelligence, every instrument of law enforcement, every financial influence, and every necessary weapon of war — to the disruption and to the defeat of the global terror network. … Every nation, in every region, now has a decision to make. Either you are with us, or you are with the terrorists. From this day forward, any nation that continues to harbor or support terrorism will be regarded by the United States as a hostile regime.

…[I]n our grief and anger we have found our mission and our moment. Freedom and fear are at war. The advance of human freedom — the great achievement of our time, and the great hope of every time — now depends on us. ... We will rally the world to this cause by our efforts, by our courage. We will not tire, we will not falter, and we will not fail.

The GWOT has failed; but failure, they say, is a better teacher than success, and if the United States can learn from this failure and how it was generated, it may be able to avoid more disasters in the future. For U.S. strategy towards China is also beginning to be portrayed in Washington, by both parties, as an apocalyptic global struggle between good and evil, with consequences that may dwarf those of the GWOT.

EVERY SIGNIFICANT country in the world has its own variant of a foreign and security establishment (or “Blob” in Ben Rhodes’ colloquial phrase); and these establishments operate in accordance with certain informal but strict doctrines. These are deeply rooted in geographical location, in specific nationalisms, and in the histories and cultures of the nations concerned. They are to a considerable extent impervious to evidence and argument, and barring defeat in war or revolutionary upheaval at home, they change only very slowly.

The Chinese, Indians, Russians, British, and Germans all have their own variants. These doctrines are sometimes defined by the identification of a particular enemy. Thus, the Polish establishment believes that Russia is the eternal and implacable enemy of Poland, and this belief is the most important element shaping Polish policy.

The doctrine of the current U.S. establishment stands out in certain key respects. The first is the scale of its ambition: the belief that the United States must seek primacy across the entire face of the globe. The second is its ideological content: the belief that the United States has a mission to spread democracy and “freedom” in the world. American religious traditions in turn help to cast this mission as a crusade for good against evil.

There is, however, one additional and paradoxical feature of U.S. foreign policy doctrine: that is, the profound and justified doubts of the U.S. establishment about how far it is really shared by the U.S. population at large. Living in what is in effect a giant island, protected by the oceans and with friendly or weak states to north and south, U.S. citizens are subject to periodic doubts about whether outside forces are really so dangerous to them, and, therefore, whether the expenditure of U.S. blood and treasure on defeating them is really justified. U.S. meta-narratives are, therefore, also heavily shaped with an eye to terrifying ordinary Americans.

THE U.S. meta-narrative of the Cold War, like the GWOT, began in response to a genuine threat: that Stalinist Communism, backed by the Red Army, would take over Western Europe and leave the United States isolated as the only large democratic and capitalist state on Earth. By the 1960s, however, Soviet communism in Europe (the critical area of contest) was on the ideological defensive. In the United States, of course, there never had been any chance of communist success.

The disastrous aspect of the U.S. Cold War meta-narrative lay largely in the fact that it was based all too closely on Senator Arthur Vandenberg’s famous advice to Dean Acheson that to get Congress and the U.S. public to accept the commitments and sacrifices necessary to resist Soviet Communism, the Truman administration needed to “scare the hell out of the American people.” Acheson commented later that to do this he helped create a portrayal “clearer than truth” of the Soviet menace to the United States.

The growth of the Cold War meta-narrative can be clearly seen in the change between George Kennan’s “Long Telegram” and “Mr. X” essay of 1946–47, and the National Security Council Paper 68 (NSC-68) of 1950, drafted chiefly by Paul Nitze. Kennan’s documents, which laid the foundation for the U.S. strategy of “containment” of the USSR, stress the hostility of Soviet Communism to all capitalist and democratic systems as well as to U.S. national interests, and say that the United States must contain Soviet ambitions through military readiness as well as economic and political means. However, at no point does Kennan say that the USSR poses a direct threat to the United States itself, or call for greatly increased U.S. military spending.

Kennan warns against U.S. “threats, blustering and superfluous gestures of outward toughness,” and to avoid threatening Soviet prestige in ways that might trap the Soviet leadership into a dangerous response. He emphasizes Soviet fears as well as ambitions, and remarks with great prescience on the underlying fragility and weakness of Soviet society; meaning that in the long run, the Communist system would likely collapse of its own accord.

NSC-68 is very different. It speaks of a “mortal threat” of the Soviet system to the United States itself, and calls for a massive military build-up in response. NSC-68 may well, therefore, be regarded as the birth certificate of the military-industrial complex. The document speaks repeatedly of America’s global ideological mission, how global leadership has been “imposed” on the United States, and how the USSR is a menace across the whole face of the world which America must meet everywhere. Kennan himself strongly criticized NSC-68, and saw it in retrospect as helping to lay the groundwork for the paranoid and militarized tendencies that helped lead the United States into the Vietnam War.