How Will the Saudi Arabia-Iran Agreement Affect Lebanon?

As the major details of the agreement remain unknown, the Lebanese debate persists.

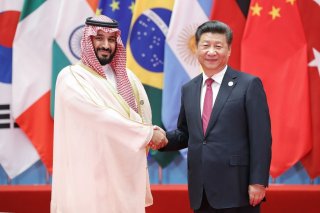

The Saudi Arabia-Iran agreement, formally known as the Joint Trilateral Statement, was brokered by China in Beijing on March 10 and has since been hailed as a significant diplomatic breakthrough. This development could have far-reaching implications for countries where Iran and Saudi Arabia vie for regional influence and fuel proxy conflicts, including Lebanon. The agreement has drawn expert analysis and commentary from both regional and global sources, evaluating the broader and more specific consequences of the deal on the security of the region, particularly for the Gulf states. This follows decades of animosity between Iran and Saudi Arabia, which reached a fever pitch in 2019 with drone attacks on Saudi oil facilities by Yemen’s Iran-aligned Houthi group amidst widespread suspicion that Iran was the actual perpetrator behind the attack.

The agreement gives Iran and Saudi Arabia two months to restore full diplomatic relations and reopen their respective embassies after having formally severed ties in 2016, following the execution of Saudi Shiite cleric Nimr al-Nimr in Saudi Arabia. Most notably, the trilateral statement asserts that both sides agree to respect the principle of state sovereignty and the “non-interference in internal affairs of states.” Although China led the agreement, it came after two years of prior mediation efforts by Iraq and Oman, which facilitated formal bilateral talks between both sides since early 2021.

Lebanese analysts and commentators are speculating whether this Saudi Arabia-Iran agreement will help alleviate tensions simmering across Lebanon and lead to the election of a compromise president for the country. Lebanon has been grappling with a persistent presidential election deadlock for over four months and is in the midst of a severe economic crisis, which the World Bank has deemed as one of the worst since the 1850s. The nation has also been governed by a caretaker government with limited powers since the parliamentary elections in May 2022.

While observers and politicians generally concur that it is too early to gauge the deal’s impact on the Lebanese situation, some believe it may ease tensions between political parties and foster a positive environment for sustained negotiations. Nevertheless, caution remains the prevailing sentiment, as intra-Lebanese dialogue might prove more difficult than anticipated, given the country’s prudence amidst a national crisis, and rapidly evolving geopolitical consequences.

To date, Iran has not officially commented on the potential repercussions of the agreement on Lebanese politics or the current deadlock. However, a few hours after the announcement, Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister, Faisal Bin Farhan, provided the only official statement from a senior Saudi government official. He remarked that Lebanon requires “a Lebanese rapprochement and not an Iranian-Saudi one,” adding that Lebanese politicians must prioritize Lebanon’s interests above all else. In a related development, the Saudi ambassador to Lebanon, Walid Boukhari, met with Lebanese parliament speaker Nabih Berri on March 13. When asked if there were any positive developments for Lebanon, Boukhari briefly replied, “certainly.”

However, following the announcement of the Saudi Arabia-Iran agreement, attention naturally shifted toward the reaction of the Iran-backed Lebanese Shiite group Hezbollah. Nominally, the group welcomed the deal. However, in a televised speech shortly after the announcement, Hezbollah Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah struck a cautious tone. He emphasized that while the deal is an “important development”—if it follows its natural course—Hezbollah is firmly convinced that it should not come at its expense. Nasrallah added that Iran does not impose its stances on Hezbollah.

Similarly, Hezbollah’s opponents in Lebanon also expressed caution following the agreement’s announcement. Samir Geagea, a prominent Lebanese politician and leader of the Christian Lebanese Forces party, which is close to Saudi Arabia and made significant gains in the 2022 parliamentary elections, emphasized that the presidential election battle is a local concern. He stated that it is “in the hands of the 128 parliamentary deputies who are ready to vote to elect a president today before tomorrow,” adding that the presidential election should not be influenced by external factors. Lebanese Forces member of parliament (MP) Pierre Bou Assi expressed skepticism about the deal, doubting its potential benefits for Lebanon. Fares Saiid, a former Christian MP and staunch critic of Hezbollah and Iranian influence in Lebanon, suggested that the effects of the deal might take months to reach Lebanon. He emphasized that Christians in Lebanon and its constitution should uphold their Arab identity, given Hezbollah’s and its allies’ allegiance to Iran.

Following Nasrallah’s speech, several observers, including Geagea, highlighted one of his statements made just a few days before the agreement. Nasrallah had said that those expecting an Iranian-Saudi deal to resolve the presidential stalemate would have to wait for a long time, leading some to conclude that he had no prior knowledge of the upcoming agreement. This prompted online commentators to derisively question the extent to which Iran consults with Hezbollah on its affairs, given the significance of the deal.

In general, when considering the entire deal and its broader regional implications beyond Lebanon, Saudis appear more cautious and moderate in their expectations, while Iranian officials and observers tend to frame it as a victory against the United States and Israel. This perspective seems to arise against the backdrop of the U.S.-brokered Abraham Accords, which normalized diplomatic relations among Israel, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan. For example, Faisal Ben Farhan recently attempted to temper grand expectations for the deal’s all-encompassing regional impact, stating that while the agreement aims to pave the way for restoring diplomatic relations, it will not necessarily resolve all disputes between Saudi Arabia and Iran. In contrast, Yahya Safavi, the Iranian top military advisor to Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, expressed high hopes, framing the agreement as the beginning of the decline of American and Zionist hegemony in the region.

Similar overstatements were also reflected in some of Hezbollah’s statements following the deal. The group began publicizing the agreement as a victory for Iran’s axis of resistance in the region, claiming that Saudi Arabia prioritized Yemen over Lebanon because it seeks to exit the brutal Yemeni war. For instance, Nabil Kaouk, a member of Hezbollah’s Central Council, said that with the deal, the Middle East has now entered a new phase detrimental to US and Israeli interests, as their aspirations to normalize relations with Israel did not lead to Iran’s isolation.

At its core, the presidential election stalemate in Lebanon is primarily due to a political standoff between the Iran-backed Hezbollah and its allies on one side, and pro-Western Sunni and Christian groups backed by Saudi Arabia on the other. The conflicting parties have been at odds since the assassination of former Prime Minister Rafik Hariri in 2005 and Syria’s subsequent withdrawal from Lebanon after decades of occupation.

The rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran in Lebanon dates back to years before the Syrian withdrawal and is largely shaped along sectarian fault lines. Since then, Saudi Arabia and Iran have more aggressively supported opposing factions in the country. Post-Syria Lebanon saw Saudi Arabia primarily seek to mobilize the Sunni sect, largely represented by the Future Movement party founded by the late Rafik Hariri. Meanwhile, Iran aimed to grow and entrench its influence through its proxy, Hezbollah. Most consequentially, the Shiite-Sunni conflict in post-Syria Lebanon reached a crisis point when Hezbollah and its major ally, the Shiite Amal party, took control of West Beirut in a military operation on May 8, 2008. This was in retaliation for then-Prime Minister Fouad Siniora’s government’s decision to disband Hezbollah’s telecommunications network and oust the airport security chief affiliated with the group.

However, in recent years, Saudi Arabia has largely disengaged from Lebanon in response to Hezbollah’s growing influence in Lebanese politics, its sway over the Lebanese state, and its reported military support for the Houthi rebels in Yemen, where Saudi Arabia has been involved in a proxy war with Iran. According to a report by the New York Times, Saudi Arabia’s dismay with Iranian and Hezbollah’s influence in Lebanese politics came to a head in 2017 when former Prime Minister Saad Hariri, the son of Rafik Hariri, resigned from his post in a televised statement from Riyadh. Hariri was reportedly forced to do so after being detained in the kingdom; both Hariri and Saudi Arabia denied the allegations. However, more recently, Saudi Arabia and other Gulf states recalled their envoys from Lebanon in October 2021 over criticism by the then-Lebanese Information Minister of Saudi Arabia’s and the United Arab Emirates’ intervention in Yemen. The ambassadors returned to Lebanon in April 2022, signaling improving relations.

In essence, the conflict in Lebanon is primarily a consequence of a power struggle between sectarian groups competing for political influence and enhanced socioeconomic advantages, rather than being solely the result of regional strife. This strife is compounded by a sectarian power-sharing system, which has been in place since Lebanon’s independence in 1943 and often comes at the expense of a strong state. Due to this power-sharing agreement, sectarianism in Lebanon has consistently played a fundamental role in shaping politics, often serving as a form of socioeconomic and political power that intersects with domestic, regional, and international contests. These dynamics are further marked by ever-shifting domestic alliances that mirror mutating regional and international power dynamics.