The U.S. Navy Wants to Bring Back the Legendary World War II Higgins Boats

The Higgins Boats of World War II were operated by men, not robots. But automated or not, their twenty-first-century successors may prove just as useful.

From Omaha Beach to Iwo Jima, the great amphibious invasions of World War II were made possible by a humble plywood boat.

Known more prosaically as the Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel (LCVP), the Higgins Boat was the nautical donkey of World War II. The brainchild of New Orleans boatmaker Andrew Jackson Higgins, the shallow-draft boats had a bow ramp that lowered to allow a rifle platoon, or a vehicle, to disembark.

That doesn’t sound like a big deal. Except that using regular boats or barges to unload troops on an open beach was a slow, laborious process, unless the invaders could capture a port (which tended to be heavily fortified). The Higgins Boat meant any open beach could serve as a debarkation point for sufficient troops, vehicles and supplies to create a meaningful bridgehead. More than 20,000 were built during World War II.

“If Higgins had not designed and built those LCVPs, we never could have landed over an open beach,” declared General Dwight Eisenhower. “The whole strategy of the war would have been different.”

Now, the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps want to bring back what it calls a “21st century Higgins Boat.” The problem is that amphibious landings have become a dicey proposition: long-range anti-ship missiles fielded by Russia, China and even armed groups like Hezbollah, make it too hazardous for amphibious assault ships to venture closer than 50 or 100 miles to shore. At the same time, the Marine Corps’ attempt to replace its 40-year-old amphibious assault armored vehicles with a new generation have run into snags, such as the vehicles—which can’t swim long distances or in rough waters—having to be ferried close to shore by another vessel.

So the Navy wants “connectors” that can ferry material to the landing zone. “This platform would enable the delivery of smaller land vehicles, weapon systems, fuel bladders, water, and electric generation equipment,” according to the Navy research proposal. “These payloads could be offloaded to support long-term advanced naval bases or operated from the watercraft to support short team Expeditionary Advanced Bases (EABs). The modular payloads could also include unmanned aerial systems (UAS) and unmanned underwater systems (UUS) launchers that could deliver unmanned systems distant from the shoreline.”

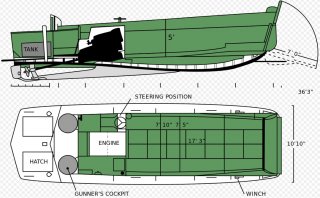

The landing craft, known by the combative name of SHARC (Small High-Speed Amphibious Role-Variant Craft), should be capable of carrying 5 tons of payload. It should also have a speed of at least 25 knots, and a range of at least 200 nautical miles. It will be about 13 feet long, with a ramp about 5 feet wide, and have a draft of less than 30 inches.

Interestingly, the Navy specifies that SHARC should be capable of remote-controlled or autonomous operation, which suggests that the Navy and Marines are hoping that robot boats can handle the donkey work of ferrying materials from transport ships to the beachhead. It should be able to power modular mission packages, which raises the possibility that the boats themselves could become drone or weapons bases.

Commercial vessels already meet some of these requirements, according to the Navy. These commercial craft “are essentially current versions of World War II Higgins Boats.” Not surprising, given that Andrew Jackson Higgins based his military boat on the shallow-draft work craft he built to service oil exploration in the Louisiana bayou.

The Higgins Boats of World War II were operated by men, not robots. But automated or not, their twenty-first century successors may prove just as useful.

Michael Peck is a contributing writer for the National Interest. He can be found on Twitter and Facebook.

Image: Wikipedia.