When Camelot Went to Japan

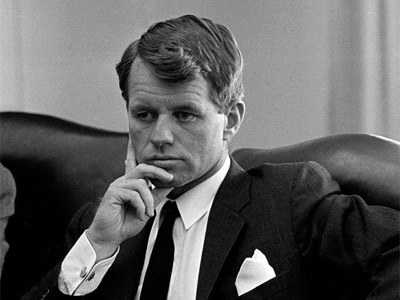

Mini Teaser: RFK's public-diplomacy trip turned the relationship around.

No sitting U.S. president had yet visited Japan, although Ulysses S. Grant had gone after leaving office. As noted, Eisenhower’s scheduled visit had been aborted in the chaos of the security-treaty crisis. Kennedy was smarting from some foreign-policy setbacks—most notably the 1961 Bay of Pigs fiasco—and wanted a diplomatic triumph. He envisioned a historic presidential visit to Japan during the 1964 reelection campaign. At its center would be a mesmerizing, human-interest reunion in Japan between the crews of PT-109 and the Amagiri, once enemies, now reconciled.

To test the waters, the president dispatched his most trusted adviser—Robert Kennedy. In Japan, Reischauer helped create an unofficial group to host the attorney general. Members of the “RK committee” included several relatively young, pro-American Japanese business and government leaders, among them the dynamic young LDP politician (and future prime minister) Yasuhiro Nakasone. Members of the RK committee worried that Japanese youth were being bewitched by Communism. Reischauer agreed that the “growing gap” between Americans and young Japanese people—the people who would be the future of the relationship—was a “truly frightening phenomenon.” They agreed that a visit from John Kennedy could help turn the tide—that Camelot could do some powerful bewitching of its own. First with Robert, then with Jack, the RK committee would show the Japanese a new, young and vigorous United States.

ON FEBRUARY 6, 1962, as Robert Kennedy’s motorcade drove through Tokyo’s streets toward a public appearance at Waseda University, reports were coming in from the CIA to expect trouble. Conferring across the jump seats of the car, the attorney general, Ambassador Reischauer and their aides discussed CIA warnings that Marxist student groups intended to disrupt the event. Memories flashed to 1960, when the thousands of protestors swarming Tokyo’s streets led President Eisenhower to cancel his visit. But despite their apprehension, as Reischauer later commented, “We decided at the last minute that it would look bad to back out.” The car slowed as it pulled in front of Okuma Auditorium, and a crowd of over five thousand students surged around it.

The students that greeted Robert and Ethel Kennedy turned out to be friendly. As Robert and Ethel pushed their way through the throng toward the auditorium, students laughed, cheered and stretched out their hands to touch them. But inside “the story was different,” as Kennedy recalled later.

Built to hold 1,500 people, Okuma Auditorium writhed with more than four thousand students. While many cheered the attorney general’s entrance, others jeered and booed. When Kennedy began to speak, Marxist students shouted and stomped their feet. One, Yuzo Tachiya, was particularly agitated. A leader in student government, he had distributed thirty thousand fliers that day to summon the crowd that now packed the auditorium. He had met with two professors who talked with him about how they were going to chair and translate the event. Tachiya watched, upset, as Kennedy substituted his own translator, “ignored the debate format set by his hosts,” and simply began speaking. The young man shouted from the audience that this was not right, that Kennedy should follow the format established by the professors who were hosting the event.

But when the Americans looked into the sea of black-uniformed students beneath the stage, what they saw, in the words of Kennedy’s assistant John Seigenthaler Sr., was “a skinny little Japanese boy” who was “tense, shouting, shouting, shouting, screaming at the top of his lungs.” If I ignore him, the attorney general thought, maybe he’ll be quiet. So he kept talking:

The great advantage of the system under which we live—you and I—is that we can exchange views and exchange ideas in a frank manner, with both of us benefiting. . . . under a democracy we have a right to say what we think and we have the right to disagree. So if we can proceed in an orderly fashion, with you asking questions and me answering them, I am confident I will gain and that perhaps also you will understand a little better the positions of my country and its people.

But Tachiya was still shouting, and “bedlam was spreading.” Kennedy recalled, “The Communists were yelling ‘Kennedy, go home.’ The anti-Communists were yelling back, and the others were yelling for everyone to keep quiet. I could see I wasn’t going to make any progress.” So Kennedy stopped talking. He acknowledged the heckler: “There is a gentleman down in the front,” he said, “who evidently disagrees with me. If he will ask a single question, I will try to give an answer. That is the democratic way and the way we should proceed. He is asking a question and he is entitled to courtesy.”

Kennedy extended his hand toward Tachiya, who grabbed it. The attorney general pulled him up onto the stage. “Bob treated him with great friendliness,” remembers Seigenthaler: putting his hand on his shoulder, telling him, “You go first.” He was “so cool,” marveled Ernest Young, “so cool.”

As the United States attorney general politely held the microphone for him, Tachiya blasted through the issues detailed on a leaflet his organization had prepared—the return of Okinawa; Article 9 of the Japanese constitution (which prohibits war making by the state) and the need for Japanese neutrality; the U.S. government’s treatment of the American Communist Party; the effect of a potential nuclear war on humanity; the CIA’s involvement in the Bay of Pigs; and America’s fledgling involvement in Vietnam. “His face,” the attorney general observed, “was taut and tense and filled with contempt.” Kennedy listened patiently, and finally Tachiya stopped talking. As Kennedy began to speak, the microphone went dead. Pandemonium broke out in the auditorium.

ROBERT KENNEDY, as Anthony Lewis of the New York Times once wrote, “rejected the politics of grins and blandness.” During the Japan visit planning, the attorney general had vetoed the normal round of receptions and photo ops. (“Nothing of any substance ever happens at a state dinner,” he said.) He wanted to meet ordinary Japanese in their daily lives. “You get him in touch with the people,” Seigenthaler told the RK committee. “He wants to meet the people.” During his visit, Kennedy debated Socialist political leaders, toured farms and factories, played football with Japanese children, walked through elementary schools, talked to university students, met with women’s groups, and watched sumo and judo demonstrations. He declined an offer to participate in the latter, sending in a replacement. (“I got thrown on my butt,” groused Seigenthaler.) One night in a bar in Ginza, Kennedy sampled sake and chatted with customers at the counter. He led some of the other Americans present in what he remembered as “a very off-key rendition” of “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling.”

Ethel Kennedy, for her part, delighted the Japanese with a formidable mix of star power and approachability. “Call me Ethel!” she demurred when greeted with deep bows and formality. She talked about her daily life with her many children and their routines at their Virginia home, Hickory Hill. “Ethel loved people,” recalled Susie Wilson, a journalist and friend accompanying her on the trip. “She chatted with any and all of them, and they responded to her genuineness, and her concern for them and their cares.”

These efforts to get to know the people of Japan marked a new approach in alliance policy. The two societies had been kept separate, and U.S. diplomacy had focused on the military-strategic sphere at the expense of other spheres—particularly the cultural one. Disturbed at this trend, Reischauer had created at the U.S. embassy the position of cultural minister, bureaucratically equivalent to the political and economic ministers. “Money spent on diplomatic and cultural activities,” he lamented, “is proportionately far more productive than that spent on military programs but is always the first to be cut, even though the sums are inconsequential compared to military budgets.”

During Kennedy’s visit, the RK committee told him that the Soviet Union was skillfully waging a “cultural offensive” in Japan, while the United States was neglecting this realm. America’s cultural missions, the RK committee members told the attorney general, were inadequate, ill suited for Japanese audiences and ineffectual. “The importance of this issue,” Kennedy commented, “was brought home to me again and again throughout our trip.”

BACK ONSTAGE in Okuma Auditorium, confusion reigned. This is a fiasco, thought Reischauer, watching students heaving chairs at one another. Realizing something had to be done, he rose and held up his hands to the audience. To his surprise, the crowd looked up at him and quieted. In his fluent Japanese, he asked the students to remain calm. Meanwhile, someone located a bullhorn and handed it to Kennedy. The attorney general began earnestly:

Image:We in America believe that we should have divergencies of views. We believe that everyone has the right to express himself. We believe that young people have the right to speak out and give their views and ideas. We believe that opposition is important. It’s only through a discussion of issues and questions that my country can determine in what direction it should go.

Pullquote: After Robert Kennedy's visit, the RK committee grew into a number of activities and institutions designed to foster an alliance between peoples rather than between governments.Essay Types: Essay

Pullquote: After Robert Kennedy's visit, the RK committee grew into a number of activities and institutions designed to foster an alliance between peoples rather than between governments.Essay Types: Essay