How the West Gets Iran's Interventionism Wrong

The West’s current “maximum pressure” approach does not work, primarily because its aim is curtailing displeasing Iranian actions without addressing the genesis of their implementation.

While many in the West are quick to ascribe Iran’s interventions throughout the Middle East to its complex history with the United States, the matter is not nearly so simple. A confluence of military, religious, economic, and historical factors—often completely ignored by many Western governments, who assume Iran’s policy of intervention and nuclear aims are solely motivated by ideological anti-Western sentiment—drives Iranian interventionism throughout the region, stretching from its ancient history to the present. These interventionist impulses are a desire for regional hegemony; aspirations to promulgate Shia Islam; efforts to reap the benefits of regional trade; and a resurgence of Persian nationalism. For the West to truly comprehend, much less correctly respond to, Iran’s actions, it must first analyze Iran from a non-Western perspective.

Perhaps the most evident impulse driving Iran’s interventionist practices is its desire to achieve regional hegemony. Just like ancient Persia, modern-day Iran is centrally located in the Middle East and surrounded by rival and weakened failed states. Two nations, in particular, Israel and Saudi Arabia—in conjunction with the Gulf Cooperation Council and Turkey—have long engaged Iran in a series of proxy wars to promote their regional agendas and expand their power. These conflicts often occur in the surrounding failed states, as the governments are not strong enough to quash them and assert control. Several recent examples include the Syrian Civil War, in which Iran backs the Syrian government and similarly aligned non-state actors such as Hezbollah; the Yemeni Civil War, where Iran supports the Houthi rebels opposing the internationally recognized government; and war-torn Iraq, where Shia militias loyal to Tehran carry out its bidding in exchange for funding and armaments. In each instance, Iran has clashed with Israel and Saudi Arabia to cement its status as a powerful actor in the Middle East.

Iran’s conflict with its neighbors is not a recent phenomenon. In its early days, the Persian Empire clashed with Rome over their Western border in Syria, frequently employing indigenous guerilla raiders on the frontiers to instigate conflict. From the sixteenth century through the nineteenth century, Iran came into conflict on all sides, from Mughal India to the east, the Ottoman Empire to the west, the Russian Empire to the north, and even the Portuguese and British Empires in the Strait of Hormuz. Throughout its history, Iran has feuded with its neighbors and rivals to achieve regional hegemonic status, to varying degrees of success.

Along with its hegemonic aspirations, another driving force behind Iran’s meddling in the Middle East is spreading its unique brand of Shia Islam. After the Islamic Schism in 632 AD, following the death of the Prophet Mohammed, Iran became one of the last bastions for Shiite Muslims. Iran is estimated to contain over 80 percent of the world’s Shia population. Iran fought several religiously motivated conflicts with its Sunni Muslim neighbors, the Ottoman Empire and Mughal India, throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as well as countless skirmishes with Sunni tribesmen before that.

Religion became far more important as a motivating force for Iran after the Iranian Revolution of 1979. During the Revolution, radical Islamic theocrats led by Ayatollah Khomeini deposed the U.S.-backed shah of Iran, Reza Pahlavi. Khomeini promptly utilized the religious fervor ignited by this coup to spread an anti-American sentiment throughout the nation, which contributed to the Iran hostage crisis. Seeing itself as the protector of Shia Muslims, this newfound emphasis on Shiism put Iran directly in conflict with Saudi Arabia, the de facto leader of Sunni Muslims and self-described “Defender of the Holy Cities.” Conflagrations between the two Islamic powers, both direct and indirect, often occur in the failed states surrounding them, showing just how interconnected Iran’s interventionist impulses truly are. The desire to spread Shiism has led to Iran’s growing influence in post-Saddam Iraq and the Syrian Civil War, much to the consternation of Saudi Arabia.

Another factor driving Iran’s interventionism is its propensity for reaping the rewards of regional trade, something it has been denied for most of its existence. The Persian Empire naturally contained a vast abundance of economic resources, additionally benefitting from its position along the Silk Road. For a time, Persia enjoyed tremendous economic prosperity. However, as the Ottoman Empire expanded economically and territorially, Persia began to lose its regional economic dominance. Eventually, as the Portuguese and British Empires began to take hold of the Indian subcontinent, clashes with Europeans became more and more frequent. Predictably, these confrontations led to Persia becoming boxed in between them and the Ottomans. Being trapped between their rivals meant Persia’s economic situation gradually deteriorated to the point where it competed with the Ottomans and imperialist Europeans to trade resources on the world market.

Contemporary Iran faces a similar economic dilemma, although in a different context. After the 1979 revolution, Iran’s interventionist activities (both religious and hegemonic) increasingly set itself in conflict against the main trading partners in the region, Saudi Arabia and the GCC. These actions have also earned the ire of the United States, which has applied stringent economic sanctions on Iran in an attempt to end its interventionist practices. These sanctions, combined with its inability to trade extensively with the GCC, have led Iran to have an abundance of in-demand economic resources, yet it cannot export them. Many experts stipulate that Iran wishes to use its interventionist practices, such as supporting Hezbollah, Hamas, and other proxies, as bargaining chips to lessen the imposed sanctions.

The fourth element of Iran’s interventionism in the Middle East is the sentiment of Persian nationalism that the Iranian government and ordinary Iranians feel. Iran views itself as the inheritor of the once-great Persian Empire and hopes to reclaim what it perceives as its lost glory. Leaders in Tehran believe that Iran’s historical significance and cultural superiority automatically permit it to have a more significant role in regional affairs. Unlike regional hegemony, this impulse is not directly about territory or political clout. Instead, it is a state of mind to justify and unify Iran’s different desires under a single idea. This form of nationalism adopted by the Iranian government also draws on the country’s Persian ancestry and prestige to influence the Iranian populace to support its interventions abroad.

Persian nationalism, especially for the current regime, is a way to define Iranian national independence in light of its cultural past. It recalls the many previous examples of the old Persian Empire being exploited and abused by foreign powers. It thus dictates why Iran must come into its own and adopt a more aggressive foreign policy. However, in other instances, it celebrates former moments of Persian greatness, particularly its cultural superiority over its neighbors. Before the revolution, Shah Reza Pahlavi relied heavily upon Persian culture by keeping the term “Shah” and utilizing his royal bloodline to relate himself to the Shahs of old. The religious regime that replaced him also used Persian nationalism to its advantage by recently reviving the pre-Islamic New Year.

Contrary to the prevailing thought in Washington and other Western nations, it isn’t Iran’s inherent hatred towards the West but rather a wide range of factors that drive its interventionism in the Middle East. The central impulses driving Iranian interventionism—regional hegemony, Shiism, trade, and Persian nationalism—must be more broadly studied by Western scholars and policymakers should they truly hope to understand why Iran undertakes the actions it does. A greater understanding of these themes can also assist politicians in knowing how to engage Iran properly, and how they will likely respond to those overtures.

Rising regional tensions and the seemingly inevitable dissolution of the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action largely show that the West’s current “maximum pressure” approach does not work, primarily because its aim is curtailing displeasing Iranian actions without addressing the genesis of their implementation. The West could reach a more mutually beneficial arrangement with Iran if they adopted a more amenable attitude towards its foreign policy concerns or at least appropriately analyzed them. Washington’s repeated classification of Iran’s interventionist actions as being purely targeted against the United States and its interests, as opposed to merely being reactionary with respect to Iran’s own economic, political, and historical environment, has thus far only poured more fuel on the fire instead of creating a workable solution.

Jake McAloon is an American historian and political analyst in the Chicagoland area. His primary areas of interest are Middle Eastern & African foreign policy formulation and implementation as well as American interventionism.

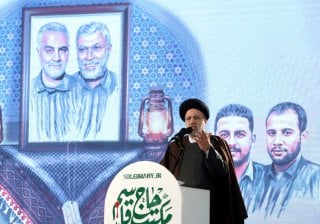

Image: Reuters.