What Would Kim Jong-un’s Death Mean for China?

"If Kim Jong-un were to die suddenly, Beijing might well be as surprised and uncertain of the implications as any other capital."

Editor's Note: This is part of a symposium asking what happens if Kim Jong-un died. To read the other parts of the series click here.

If Kim Jong-un were to die suddenly, Beijing might well be as surprised and uncertain of the implications as any other capital.

Although China has a closer relationship with North Korea than any other country, that relationship is not as warm as is widely assumed. Indeed, ties between Pyongyang and Beijing have been incrementally if inconsistently eroding for two generations. Mao Zedong and Kim Il-Sung were comrades-in-arms, although even their relationship was not always copacetic. The generation of Chinese leaders that succeeded Mao and Deng Xiaoping never fully warmed to North Korean successor Kim Jong-il, who never really forgave them for extending formal diplomatic recognition to the South Korean government in 1992.

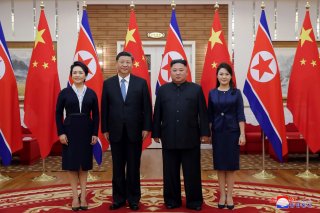

Xi Jinping inherited Beijing’s relationship with Kim Jong-un, which has fluctuated considerably. The third-generation Kim’s execution of his uncle Chang Song-taek and presumed role in the assassination of his own half-brother Kim Jong-nam reportedly was due in part to the younger Kim’s suspicions that their personal ties in Beijing made them overly susceptible to Chinese influence. This almost certainly has somewhat hindered both North Korean ties and Beijing’s detailed knowledge of internal developments in Pyongyang. In addition, earlier in Kim Jong-un’s tenure, when he was taking escalatory actions with the North’s nuclear and missile programs in violation of UN sanctions, China imposed greater diplomatic pressure and economic sanctions on Pyongyang than it ever had before.

The relationship has eased over the past three years, partly as a result of U.S. President Donald Trump’s diplomatic engagement with Kim, which prompted Xi to pursue more frequent and friendly interactions with Kim. But Kim has probably reciprocated with Xi as much if not more for the purpose of playing Beijing and Washington off against each other, than to forge a tight and exclusive relationship with China.

On the balance sheet, Beijing rhetorically retains its “close as lips and teeth” relationship with Kim, but persistent mutual mistrust, Kim’s determination to remain an independent actor, and his suspicion and probable isolation (if not elimination) of other North Korea elites who might be informants for Beijing, suggest that China probably is not well-positioned to have full knowledge of what is happening in Pyongyang’s inner circle either now or in the immediate aftermath of Kim’s death (when it happens). Nonetheless, Chinese leaders would mobilize whatever channels of communication they have—both formal and informal—to assess the situation and seek to preserve Beijing’s interests and equities in North Korea. They are probably not in a position to play a decisive role in determining who Kim’s successor is, and would instead endeavor to work quickly to establish a good working relationship with whomever North Korean Communist Party and military leaders designate—including Kim’s younger sister Kim Yo-jong, reportedly a likely candidate. Chinese leaders will be neuralgic about any risk of instability in North Korea, and thus will do whatever they can to encourage a stable succession process.

Beijing will both presume and pursue a closer relationship with Kim’s successor than Washington can expect to have, but this would not necessarily be entirely at Washington’s expense. Chinese leaders still share both the U.S. goal of denuclearization in North Korea and support for economic reforms there that would improve conditions for the North Korean people. Accordingly, Beijing is likely to pursue a relationship with Kim’s successor that advances both of those objectives.

Paul Heer is a Distinguished Fellow at the Center for the National Interest dealing with Chinese and East Asian issues. He served as National Intelligence Officer for East Asia from 2007 to 2015. He has since served as Robert E. Wilhelm Research Fellow at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for International Studies and as Adjunct Professor at George Washington University’s Elliott School of International Affairs. He is the author of Mr. X and the Pacific: George F. Kennan and American Policy in East Asia (Cornell University Press, 2018).