The Story of How Japan Sunk Britain's Best Battleship, the HMS Prince of Wales

Prince of Wales was the only modern battleship lost by the Allies during the war.

Here's What You Need To Remember: This defeat demonstrated that battleships could not hope to survive without support from aircraft, either from carriers or land bases.

More From The National Interest:

Where World War III Could Start This Year

How the F-35 Stealth Fighter Almost Never Happened

Russia Has Missing Nuclear Weapons Sitting on the Ocean Floor

How China Could Sink a U.S. Navy Aircraft Carrier

Battleships are generally best known by their guns, and for good reason. A ship carrying eight sixteen-inch guns may have the same weight of broadside as one carrying twelve fourteen-inch guns, but the larger guns generally have longer ranges and more penetrating power than the smaller weapons. Increasing gun sizes during and after World War I, therefore, were a matter of considerable attention. The best British battleships carried fifteen-inch guns, as did the most advanced German vessels. American and Japanese ships carried fourteen-inch guns. Near the end of the war, both the Americans and Japanese laid down ships with sixteen-inch guns. After the war, the Royal Navy planned to trump the Imperial Japanese Navy and the U.S. Navy by arming a new class of battleships with eighteen-inch guns.

The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 ended that dream, and limited guns to sixteen inches. The Royal Navy was granted special dispensation to build two ships with sixteen-inch guns, in order to match the Americans and the Japanese. The 1930 London Naval Treaty reduced the number of capital ships allocated to each navy, but did not change the gun limitations. The treaties allowed older vessels to be replaced after a certain time, and in the mid-1930s, Japan, the United States and the United Kingdom began to plan for a new generation of battleships. The British, suffering from severe financial constraints, wanted to limit the size and expense of the new battleships as much as possible. Accordingly, the British proposed that all new battleships be limited to fourteen-inch guns. In accordance with this hope (and not wanting to disrupt negotiations), the Royal Navy designed its newest class of battleships around the fourteen-inch weapon. The 1936 London Naval Treaty established the fourteen-inch limit, but contained a clause that lifted the limit to sixteen inches if any one of the original signatories did not sign. Japan opted out of the treaty (and began building battleships with eighteen-inch guns), and the United States took advantage of this clause by designing its new ships to carry the sixteen-inch gun. Having rejected a proposal to arm the ships with triple fifteen-inch guns, the British did not want to accept any delays in construction that a redesign would have necessitated.

This left the Royal Navy at a disadvantage. The naval architects tried to solve the problem by equipping the new class of warships with twelve fourteen-inch guns in three quadruple turrets. Unfortunately, this led to a top-heavy design, and the “B” turret on the design had to be reduced to a twin. Thus, while the new American battleships carried nine sixteen-inch guns and the new Japanese ships nine eighteen-inch guns, the British ships carried only ten fourteen-inch guns. Moreover, the complexity of the quadruple turrets created problems in several early engagements, with fire slowing because of faulty mechanisms and overcrowding.

Prince of Wales, third ship of the class, entered service in early 1941. The name, after a title that has been given to the heir apparent to the English monarchy since the thirteenth century, had previously been used for at least five Royal Navy warships. Prince of Wales displaced thirty-five thousand tons, and could make twenty-eight knots, carrying sixteen 5.25-inch dual-purpose guns as a secondary armament. Like its sisters, it was well armored, although there were some questions about the sufficiency of protection for its guns and superstructure. Based on the idea that Royal Navy vessels would always have access to refueling bases, the ships of its class were designed with relatively short ranges.

While still under construction, it suffered a bomb hit that led to severe flooding. Its commissioning was hurried due to the threat posed by the German battleships Bismarck and Tirpitz. When Bismarck and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen broke for the Atlantic in May 1941, Prince of Wales put to sea before fully working out in trials, with civilian engineers remaining on the ship. Prince of Wales accompanied Hood, the most famous warship of the Royal Navy at the time, constituting a fast squadron with the best chance of catching and destroying the Germans. The two battleships, accompanied by several destroyers, steamed north in an attempt to intercept the German task force in the Denmark Straits.

Hood and Prince of Wales successfully made contact, and the battle was joined on the night of May 24, 1941. Hood was struck by a salvo from the Bismarck, and promptly exploded and sank. Prince of Wales, although still facing some teething troubles, gave a good account of itself against the German battleship. Although it suffered seven hits, it managed to hit Bismarck three times, causing a fuel leak and limiting Bismarck’s speed. Its main armament no longer operative because of mechanical problems, Prince of Wales broke off the action and began to shadow Bismarck. Because of low fuel, however, Prince of Wales was forced to break off the chase, and played no role in the final destruction of German battleship.

After six weeks of repairs, Prince of Wales transported Winston Churchill to Newfoundland, where he met with Franklin Roosevelt and helped hammer out the naval strategy of the Western allies. In October, Prince of Wales was dispatched to Singapore in order to counter the increasing Japanese threat to British possessions. It and the battlecruiser Repulse formed the nucleus of the British Far Eastern Fleet. Upon arrival it became the most modern, powerful battleship in the Pacific (Japan’s Yamato would not enter service for another couple of weeks).

The Japanese were well aware of the threat that Prince of Wales and Repulse posed to their offensive plans. They detailed the battlecruisers Kongo and Haruna (the former itself built in a British yard) to meet the two Royal Navy ships and protect the invasion fleets. There was no need. Admiral Tom Phillips did not believe that Pearl Harbor conclusively demonstrated the lethality of air power against battleships. The Pearl Harbor attack was a surprise; the American ships were at anchor and could not maneuver. On December 8, Admiral Phillips sortied his two ships in an effort to intercept and destroy the Japanese task forces attacking Malaya.

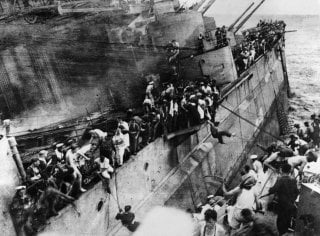

On December 10, Prince of Wales and Repulse were caught in the open sea by eighty-seven Japanese aircraft. Repulse suffered five torpedo hits, Prince of Wales four. Both ships sank, although most of the crews of each were saved. The attacking Japanese planes behaved, by all accounts, in an honorable manner. They made no effort to attack British destroyers during rescue operations, and it is held that the Japanese squadron leader flew low and waggled his wings above the surviving British ships as Prince of Wales sank. Admiral Phillips gallantly decided to go down with the ship. Winston Churchill felt that the destruction of Prince of Wales and Repulse was a greater blow to Allied sea power than the Pearl Harbor attack. Certainly, it demonstrated that battleships could not hope to survive without support from aircraft, either from carriers or land bases.

Prince of Wales could have made an important contribution in the Pacific, had it not faced an impossible task. The Kongos were excellent ships, but no match for a modern battleship. The Japanese might have approached the conquest of Southeast Asia with considerably more caution if they still had a pair of fast battleships to contend against. Prince of Wales was the only modern battleship lost by the Allies during the war.

Robert Farley, a frequent contributor to TNI, is author of The Battleship Book. He serves as a Senior Lecturer at the Patterson School of Diplomacy and International Commerce at the University of Kentucky. His work includes military doctrine, national security, and maritime affairs. He blogs at Lawyers, Guns and Money and Information Dissemination and The Diplomat. This article first appeared in 2017 and is being republished due to reader interest.

Image: Wikimedia.