Misunderestimating Bush and Cheney

Mini Teaser: George W. was no puppet of his Vice President—and for better or worse, we're still living in the world he built.

Peter Baker, Days of Fire: Bush and Cheney in the White House (New York: Doubleday, 2013), 816 pp., $35.00.

A SPECTER is haunting Washington—the specter of George W. Bush. President Obama may have spent almost five years in the White House by now, but it’s still possible to detect the furtive presence of a certain restless shade lurking in the dimmer corners of the federal mansion. Needless to say, this is something of a first: usually U.S. presidents have to die before they can join the illustrious corps of Washington ghosts, and 43 is, of course, still very much alive in his tony Dallas neighborhood, by all accounts enthusiastically pursuing his new avocation as an amateur painter. Yet his spirit is proving remarkably hard to exorcise.

Anyone who doubts this need only consider the current debate about how to deal with Bashar al-Assad. The pollsters and the pundits have found a remarkably stubborn public consensus against the use of force, and the reasons for this reluctance invariably circle back to the case of a previous Baathist dictator who stood accused of using weapons of mass destruction against his own citizens. America’s war against Saddam Hussein may be history, but for once the American people’s notoriously flabby short-term memory has not failed them. They have distinctly little appetite for anything that looks like a redo.

So how could George W. Bush, of all people, have created such a potent legacy? As New York Times White House correspondent Peter Baker reminds us in his magisterial new book Days of Fire, Bush left office as one of the most unpopular presidents of modern times. The Iraq War was clearly the signal failure of his presidency—a point now conceded even by many of his erstwhile supporters. But that’s just the first item in the index of errors. What about the shameful embrace of torture as a principle of the so-called global war on terror? The bewildering insouciance toward the war in Afghanistan? The self-destructive contempt for America’s allies? The fumbling response to the Katrina disaster? The policies that paved the way for the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression?

Given this list of cock-ups, it would have been understandable if Baker had chosen to structure his narrative as an 816-page affidavit for the prosecution. There are still plenty of short-fused Bushophobes out there, so a hatchet job might have made for great sales. But that would also be bad history. For better or for worse, we—and President Obama most of all—still live in the world that Bush built.

Think about it. The prison at Guantánamo Bay still operates. The drone war goes on—the current president, indeed, has expanded it far beyond Bush’s wildest imaginings. As for the National Security Agency’s vast warrantless-surveillance schemes set up in the years after 9/11, the current White House hasn’t missed a beat there, either. Indeed, despite Obama’s promises to guarantee government transparency and protect whistle-blowers, his White House has gone after leakers with a ferocity that puts George W. to shame. (The current administration has brought charges against seven people under the World War I–era Espionage Act; the previous White House prosecuted only one.)

So could one, indeed, argue that the Bush presidency produced anything positive? In his efforts to provide balance, Baker does his best to make the case for Bush and Dick Cheney. He argues that this duo

accomplished significant things. They lifted a nation wounded by sneak attack on September 11, 2001, and safeguarded it from further assault, putting in place a new national security architecture for a dangerous era that would endure after they left office. At home, they instituted sweeping changes in education, health care, and taxes while heading off another Great Depression and the collapse of the storied auto industry. Abroad, they liberated fifty million people from despotic governments in the Middle East and central Asia, gave voice to the aspirations of democracy around the world, and helped turn the tide against a killer disease in Africa. They confronted crisis after crisis, not just a single “day of fire” on that bright morning in September, but days of fire over eight years.

Baker’s effort to illuminate these aspects of the story won’t make him any friends on the left. Far from it. But, again, the continuities are difficult to deny. The newly elected Obama happily continued the economic emergency measures instituted by Bush in the waning days of his term. The Troubled Asset Relief Program and the bailout for the U.S. automotive industry—some of the most far-reaching interventions in the national economy ever undertaken—were launched by the laissez-faire Texas conservative, not the community organizer from Chicago. And though few Americans seem to have noticed, those programs worked out pretty well in the end—and both presidents can rightfully claim a share of the credit.

Obama also has kept No Child Left Behind, Bush’s signature education reform, maintained the costly Medicare prescription-drug program, and expanded the higher fuel-economy standards and renewable-energy incentives that Bush passed in his second term. “While Obama ran against Bush’s tax cuts, he ended up preserving roughly 85 percent of them, reversing them for just the top 1 percent of American taxpayers,” Baker writes. “And Obama made one of his highest second-term priorities an overhaul of the immigration system, moving to complete Bush’s unfinished mission.” All correct.

In short, it’s too easy to diss George W. Bush. For many of his detractors, he’s still a walking caricature: Dubya, the Shrub, the lock-jawed dope of Will Ferrell’s road show. But Baker convincingly argues that there’s no understanding where we are today unless we take a cold-eyed look at the reign of Bush and Cheney.

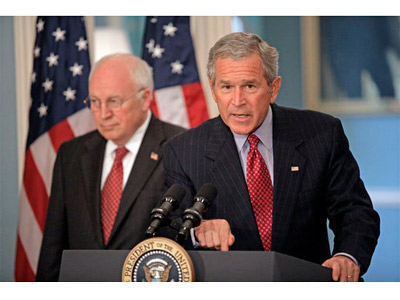

YES, LET’S not forget Cheney, so loathed on the left. Baker shrewdly opted to structure this book as a dual biography, the story of an unprecedented partnership between the president and his deputy. Previous accounts, Baker believes, have tended to miss the full complexity of the two men’s relationship. “Popular mythology had Cheney using the dark side of the force to manipulate a weak-minded president into doing his bidding,” Baker writes. “The image took on such power that books were written about ‘the co-presidency’ and ‘the hijacking of the American presidency.’” But Baker says this is nonsense: the “cartoonish caricature . . . overstated the reality and missed the fundamental path of the relationship.”

No doubt Cheney made himself into the “most influential vice president in American history”—a position he achieved through his unparalleled knowledge of the inner workings of Washington, which he gleaned through decades of service in both the executive branch and Congress. Yet Baker goes on to show how Cheney blew it. Ultimately he squandered this influence as his president moved to the center in his second term. While the basic arc of Bush’s life is by now familiar to most politically interested Americans (his early business failures, his reinvention as a baseball team owner, his fight against alcoholism and his redemption through revivalist Christianity), Cheney’s biography is still obscured by myth, partisan resentment and his own sere public persona. I, for one, was shocked to realize that Cheney is actually just a mere five years older than his president: I’d assumed (like many Americans, I suspect) that he was at least fifteen or twenty years Bush’s senior. Maybe it was just his glabrous head, but Cheney always exuded, and continues to exude, a surly gravitas that the peevish Bush never mastered.

Nowadays we tend to think of Cheney as a kind of cranky old battle robot. But there was a time when he was more of an enfant terrible, a remarkable political prodigy. In 1976, thanks to a wily political patron named Donald Rumsfeld, Cheney became, at age thirty-four, the youngest White House chief of staff in history (under President Gerald Ford). Bossing around underlings came naturally to him. In 1980, as a fledgling congressman, he ran for and won the number-four House post in the Republican Party. At the end of the decade he assumed the job of secretary of defense under President George H. W. Bush, in which capacity he was part of the team that planned and implemented the successful 1991 Gulf War, including the fateful decision to leave Saddam in power once allied forces had expelled him from Kuwait—a decision that Cheney stoutly defended, alleging that it would have been foolhardy to go all the way to Baghdad. Later he changed his mind. It was a career that gave Cheney unparalleled insight into the technology of inside-the-Beltway power.

Nowadays we tend to think of Cheney as a kind of cranky old battle robot. But there was a time when he was more of an enfant terrible, a remarkable political prodigy. In 1976, thanks to a wily political patron named Donald Rumsfeld, Cheney became, at age thirty-four, the youngest White House chief of staff in history (under President Gerald Ford). Bossing around underlings came naturally to him. In 1980, as a fledgling congressman, he ran for and won the number-four House post in the Republican Party. At the end of the decade he assumed the job of secretary of defense under President George H. W. Bush, in which capacity he was part of the team that planned and implemented the successful 1991 Gulf War, including the fateful decision to leave Saddam in power once allied forces had expelled him from Kuwait—a decision that Cheney stoutly defended, alleging that it would have been foolhardy to go all the way to Baghdad. Later he changed his mind. It was a career that gave Cheney unparalleled insight into the technology of inside-the-Beltway power.

But there was something else at work as well. Cheney’s experience in the 1970s, when the post-Watergate Congress was feverishly working to curtail presidential prerogatives wherever it could, left him with a markedly expansive view of executive power. In Cheney’s opinion (one he shared with Rumsfeld), the job of the president and his staff was to push back aggressively against any efforts to impinge upon presidential authority.

It was Cheney, indeed, who realized that the oft-derided office of the vice presidency was an ideal platform for anyone determined to mount an all-out defense of White House supremacy. The story of how Cheney ran Bush Jr.’s vice presidential selection committee, only to end up getting the job himself, has been often repeated. Baker’s version is cautious and nuanced, but still illuminating. “The official version is that Bush never gave up on the idea of having Cheney as his running mate and wore him down,” Baker writes. There is some evidence for this scenario—Cheney, for example, refused the job the first time Bush offered it to him. Yet Baker concedes that it’s hard to entirely dismiss the notion that Cheney, the maestro of plausible deniability, had skewed the whole process in his favor, a verdict that Barton Gellman’s impressive book Angler, which details the efforts of Cheney and his aide David Addington to obtain compromising material about other potential candidates during the vetting process, suggests. Baker observes:

Pullquote: There is no evidence that Cheney ever succeeded in persuading Bush to adopt positions that he wasn't already inclined to accept; there are, however, quite a few cases where Bush defied him.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review