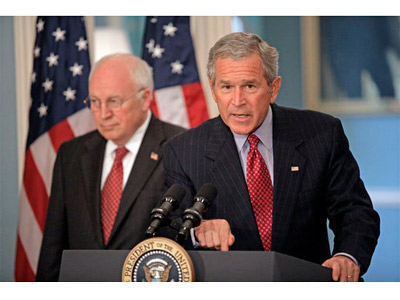

Misunderestimating Bush and Cheney

Mini Teaser: George W. was no puppet of his Vice President—and for better or worse, we're still living in the world he built.

Yet some losing candidates and even some Cheney friends were convinced it was all an elaborate orchestration. “Cheney engineered the whole vice president thing,” said one friend. “The brilliance of Cheney is he let the other alternatives just light themselves on fire, one after the other. It was perfect.” Cheney never said as much to this friend, but it says something that someone close to him would come to this conclusion.

If you’re a student of the science of power, you’ll relish the passages that describe Cheney’s maneuverings. From the very beginning of his vice presidency we see Cheney deftly recalibrating the bureaucratic machinery to his own ends (for example, by melding his high-powered staff with the president’s to an extent that no one else had ever dared to do before him).

One of the most intriguing accounts in the book involves Cheney’s effort, early in 2001, to gut U.S. approval of the Kyoto Protocol, which had been signed by Clinton. Cheney urged Bush to sign a letter that robustly denounced the Kyoto Protocol and rejected the notion of carbon caps (despite a campaign promise favoring carbon caps that actually enjoyed the support of some influential members of his team), then staged an extraordinary end run around the rest of the White House staff.

Cheney personally carried the letter to the Republican leadership in the Senate. Neither Christine Todd Whitman, Bush’s administrator of the Environmental Protection Agency, nor Secretary of State Colin Powell, nor National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice was informed ahead of time. Baker persuasively contends that this moment, months before 9/11, marked the real start of the Bush administration’s fateful penchant for unilateralism. The Kyoto letter “made only passing mention of working with other countries to find alternatives to the flawed pact, and no one had prepared the allies for what was coming, feeding the impression of a go-it-alone attitude on the part of the new president.”

The Kyoto episode is a great example of how that go-it-alone philosophy toward other countries mirrored a similar mind-set toward certain checks and balances within the government itself. The vice president’s determined refusal to provide details of his meetings with industry representatives during his deliberations on energy policy, for example, was grounded in the same philosophy of executive dominance. Watergate always loomed large for the old boy; he was determined to engage in his personal rollback campaign, bolstering the presidency by shedding congressional restraints imposed during the Ford administration. Cheney had an opening that was denied his predecessors, too. For obvious reasons, American wars have always tended to empower presidents, and the period following the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington merely affirmed this pattern.

BAKER’S ACCOUNT of 9/11 and its aftermath makes for a gripping read and goes a long way toward illuminating the motives of White House policy makers who had to confront the possibility that the attacks were merely a prelude to an even more apocalyptic assault on the United States:

But Bush saw one of the towers fall and thought to himself that no American president had ever seen so many of his people die all at once before. Three thousand had been killed in the deadliest sneak attack in American history, all on his watch. At the time, he thought it was even more.

He reminds us that Bush, whose presidency was floundering, initially had a rocky time responding to the crisis, but then rebounded to remarkable effect starting with his impromptu remarks at the still-smoking ruins at ground zero in New York. For a while, buoyed by a remarkable bipartisan urge to unity and revenge, his popularity ratings soared to the 90 percent mark.

As it happened, Cheney, as James Mann vividly reported in The Vulcans, was an alumnus of many continuity-of-government exercises during the Cold War era, and his concurrent sensitivity to threats tended to feed the general sense of vulnerability and paranoia. (It was the vice president, for example, who urged Bush to keep away from Washington for most of the day on 9/11 itself; though that may have been a smart move on security grounds, it ultimately exposed the president to criticism.) Baker does an excellent job of summoning up the febrile atmosphere of the fall of 2001, when proliferating false reports and a general state of jumpiness merged with the mysterious anthrax-by-mail attacks and accounts of Osama bin Laden’s meeting with renegade Pakistani nuclear scientists to keep a nation’s nerves on end. And then, in October, a biological-weapons sensor went off in the White House:

“Mr. President,” Cheney started soberly, “the White House biological detectors have registered the presence of botulinum toxin and there is no reliable antidote. Those of us who have been exposed to it could die.” Bush, taken aback, sought to understand what he had just heard. “What was that, Dick?” he asked. Colin Powell jumped in. “What is the exposure time?” he asked. Bush and Condoleezza Rice assumed he was calculating his last time in the White House, trying to figure out whether he had been exposed too. It turned out he had been there within the possible exposure window.

Needless to say, it turned out to be a false alarm. But it’s a vivid example of the not entirely unjustified fears that vexed decision makers at the time.

In contrast to the portraits painted by his enemies, though, the vice president’s actual power over Bush was limited. Cheney was an enabler, someone who smoothed the way, not a man who gave orders to his superior. Baker notes that there is no evidence that Cheney ever succeeded in persuading Bush to adopt positions that he wasn’t already inclined to accept; there are, however, quite a few cases where Bush defied him. Despite Cheney’s urgings, Bush refused to stage the invasion of Iraq in the spring of 2002. And Cheney also strongly opposed Bush’s effort to obtain UN authorization for the war when it finally took place a year later. (The U.S. draft resolution was withdrawn when it became clear that other members of the UN Security Council were prepared to veto it.)

As Baker tells the story, Cheney’s enormous influence over the president was not a figment of the conspiracy theorists’ imagination—but nor did it prove as permanent as they might have supposed. In Bush’s second term in office, eager to craft a positive legacy that would outlive the shame of the Iraq fiasco, the president shifted to the center, leaving Cheney’s neoconservative camarilla suddenly isolated. For years, the neocons had held sway, isolating the State Department in their machinations to enmesh Washington in a war of liberation in Iraq. They succeeded all too well. The disasters that ensued ended up creating shock, if not awe, in Bush’s mind. After the thumping of the 2006 midterm elections, Bush started to shift course. The neocons were out; the realists were in. At the Department of Defense, Rumsfeld eventually gave way to Robert Gates, a major moderating influence on foreign policy. (The shift also deprived Cheney of a crucial ally in interagency squabbles.) Condoleezza Rice assumed Powell’s old job as secretary of state, where she lobbied for a whole range of more moderate foreign-policy positions on fronts ranging from Iran to North Korea. Baker notes that her own bond with the president arguably contained a great deal more of genuine friendship and intimacy—fueled, at times, by a shared love of sports and exercise—than Bush’s relationship with Cheney. (At one point, as Baker recalls, Rice once inadvertently referred to her boss as “my husband” in the presence of journalists.) “By the latter half of his presidency,” Baker writes, Bush “had grown more confident in his own judgments and less dependent on his vice president.”

In one of the book’s most vivid scenes, Bush’s national-security aides convene to discuss the proper course of action against an illicit Syrian nuclear reactor being built with North Korean assistance. Should the United States assist an Israeli strike against the facility? Or simply let the Israelis go it alone? Cheney is the only one at the table to argue, forcefully, for a U.S. raid on the reactor. Bush asks for a show of hands: “Does anyone here agree with the vice president?” No one, as it turned out.

Just in case there’s any doubt about the extent of Cheney’s political isolation by the end of Bush’s second term, Baker frames his book with an account of Cheney’s abortive efforts to persuade Bush to grant a presidential pardon to I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, the Cheney aide convicted by a jury of perjury during a federal investigation to determine the culprit responsible for outing Valerie Plame as a CIA agent (apparently in retribution for an op-ed written by her ex-ambassador husband Joseph Wilson that undercut the administration’s case for war in Iraq). While Bush was willing to commute Libby’s sentence, he refused to overturn the verdict of the jury, opening a breach between him and his vice president that undermines the customary description of Cheney as a Darth Vader figure, capable of shifting an indecisive president through minor exertions of the Force. As Baker shows us in the book on many occasions, Bush was far from pliant.

Pullquote: There is no evidence that Cheney ever succeeded in persuading Bush to adopt positions that he wasn't already inclined to accept; there are, however, quite a few cases where Bush defied him.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review