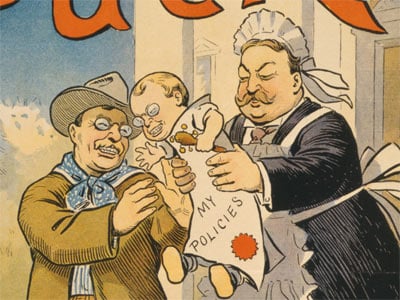

Teddy Roosevelt and Taft: The Odd Couple

Mini Teaser: Few American stories of personal fellowship are as poignant as the Roosevelt-Taft friendship—and its brutal disintegration.

Based on their experiences under Harrison, Taft would have appeared to be on the faster track. The president found his temperament much more to his liking than that of Roosevelt—who, the president complained, seemed to feel “that everything ought to be done before sundown.” Sensing the president’s disdain, Roosevelt complained to his sister that his fight against corruption in federal employment practices was conducted with “the little gray man in the White House looking on with cold and hesitating disapproval.” Goodwin writes that Harrison considered firing the underling but feared a backlash from the large numbers of people who appreciated his forceful anticorruption agitations. Conversely, Harrison took an immediate liking to Taft, inviting him to call at the White House “every evening if convenient.” Harrison eventually nominated the thirty-four-year-old Taft to a seat on the U.S. Circuit Court, the second highest in the federal judicial system. Roosevelt, meanwhile, returned to New York City as police commissioner.

THE NEXT Republican president, William McKinley, developed similar views of the two men. When he needed a judicious and calm figure to become governor-general of the Philippines, he chose Taft. But when Roosevelt’s friends sought to get him appointed assistant naval secretary, McKinley hesitated. He told one Roosevelt promoter, “I want peace, and. . . . I am afraid he is too pugnacious.” But eventually he relented and gave Roosevelt the job, to which the new assistant secretary brought a whirlwind of activity aimed at getting the navy ready for a war with Spain that he not only foresaw but also welcomed with a kind of romantic martial spirit.

When war came, Roosevelt embraced it not only philosophically but also physically, organizing his “Rough Rider” militia unit that distinguished itself in the campaign to capture the crucial city of Santiago in Cuba. Leading his famous charge up Kettle Hill on the San Juan Heights, he demonstrated a disregard for his personal safety that was courageous and foolhardy in equal measure. That single action cemented his place among his countrymen as the most stirring personality of his time. He already had become nationally known for his impetuous ways and reformist zeal; now he was a national hero.

Roosevelt promptly parlayed his new status into a successful run for New York governor. His budding progressivism ran headlong into the conservative doggedness of the state’s political bosses, particularly Senator Thomas Platt, who ran the New York Republican machine. Although Roosevelt sought to nurture a working association with Platt, he ran afoul of the senator when he pushed for a business franchise tax on corporations—streetcar firms, telephone networks, telegraph lines—that had been given lucrative business opportunities through state franchises. “You will make the mistake of your life if you allow that bill to become a law,” Platt warned, hinting at a suspicion that Roosevelt harbored Communist or socialist tendencies. Roosevelt countered: “I do not believe that it is wise or safe for us as a party to take refuge in mere negation and to say that there are no evils to be corrected.” He got the bill passed, though with some amendments designed to placate Platt if possible. The party boss sought to put a friendly face on the outcome, but the machine now considered Governor Roosevelt a marked man.

Undeterred, Roosevelt sent to the legislature a call for state actions to curtail the growth and power of corporate trusts, the increasingly monopolistic enterprises that sought to squeeze out competitors, often through corruption and dishonesty, and thus gain dominance over crucial burgeoning markets. Taking a cue from his friend Elihu Root, one of the country’s leading lawyers and war secretary in the McKinley administration, Roosevelt carefully crafted his language on the trusts to avoid any hint of radicalism. He stressed, “We do not wish to discourage enterprise; we do not desire to destroy corporations; we do desire to put them fully at the service of the State and the people.” Notwithstanding this measured approach, which was to become a hallmark in subsequent years, the antitrust effort never got off the ground. The reason, he concluded, was that the problem had not seeped sufficiently into the political consciousness of the people.

But Roosevelt’s apostasy was never forgotten by Boss Platt and his cronies. They sought to oust him from the governor’s chair and perhaps even deny him renomination at the next GOP convention. The solution came in the form of a movement to get Roosevelt on the McKinley ticket as vice president in the 1900 balloting. Roosevelt wasn’t sure he could handle being stuck in such a passive, backwater job, but the threat of being upended as governor proved a powerful incentive. As his friend Henry Cabot Lodge succinctly put it, “If you decline the nomination, you had better take a razor and cut your throat.”

Less than seven months after assuming the vice presidency, TR became president, to the consternation of his foes, following the assassination of McKinley in September 1901. The country’s new chief executive was just forty-two years old.

“I am President,” he declared with characteristic audacity, “and shall act in every word and deed precisely as if I and not McKinley had been the candidate for whom the electors cast the vote for President.” Roosevelt proved adept in working with the congressional opposition and in encasing his antitrust goals in descriptive language designed to be moderate, measured and balanced. Federal power over the trusts, he declared, must be “exercised with moderation and self-restraint.” And he argued that Democratic calls to eradicate all trusts would “destroy all our prosperity.” But he encountered an apathetic public on the issue, just as he had during his days as New York governor.

ENTER S.S. MCCLURE. He hit upon the idea of sending his talented young writer, Ida Tarbell, after a single trust, thus rendering the story vivid and understandable. She chose John D. Rockefeller’s Standard Oil, “the Mother of Trusts.” In a twelve-part series that later became a best-selling book, Tarbell documented, among other things, how Rockefeller induced corrupt railroad magnates to impose discriminatory freight rates upon his independent rivals, thus killing off competition and cornering the mushrooming oil market. The reaction was electric. Suddenly the trust problem became a matter of high concern to the nation.

This helped pave the way for Roosevelt’s progressive agenda, which he pressed with his usual urgency. He pushed through a reluctant legislature the Hepburn Act, which authorized the Interstate Commerce Commission to set the rates charged by railroads to their shipping customers—a direct reply to Tarbell’s famous Rockefeller series. He got Congress to create the Department of Commerce and Labor (later split into two separate departments), with regulatory powers over large corporations, and to pass legislation expediting prosecutions under the Sherman Antitrust Act. Responding to other “muckraking” journalism in McClure’s Magazine and elsewhere, he fostered passage of the Meat Inspection Act and the Pure Food and Drug Act. Roosevelt’s Justice Department filed suit against the Northern Securities Company under antitrust laws and brought the company down. It broke up Standard Oil and went after the beef trusts that had colluded to parcel out territories and fix prices, resulting in sharp cost increases for consumers of meat.

In addition, he personally—and adroitly—handled a coal-strike crisis that threatened the national economy. And he preserved some 230 million acres in public trust through creation of a multitude of national parks, forests and monuments. In foreign affairs, he set in motion the building of the Panama Canal by fomenting a successful Panamanian revolt against Colombia and then negotiating with the new Panamanian nation for rights to the swath of isthmus needed for the canal. He put himself forward as mediator to foster a negotiated end to the Russo-Japanese War, a bit of diplomacy that earned him a Nobel Peace Prize.

Roosevelt deployed federal power on behalf of national goals, far beyond anything seen since the Civil War. But two realities surrounding the Roosevelt presidency merit attention. First, the Rough Rider president, in bringing progressive precepts into the national government, stopped short of the kinds of redistributive economic policies favored by more radical progressives of the era. His aim was to level the playing field by outlawing practices and privileges that allowed favored groups to thrive at the expense of the mass of ordinary citizens. He didn’t embrace the goal of a graduated income tax, for example. And, although he despised the high tariff rates of the McKinley administration, he shied away from attacking those discriminatory levies because he wasn’t prepared to expend the kind of political capital that would have been required for such a fight against party bosses committed to protectionist policies.

Indeed, Roosevelt constantly expressed his preference for middle-ground approaches that raised the ire of both laissez-faire conservatives and more radical elements of the progressive movement. Even as New York governor, he confessed that he wasn’t sure which he regarded “with the most unaffected dread—the machine politician or the fool reformer.” He added that he was “emphatically not one of the ‘fool reformers.’” As president he declared that “there is no worse enemy of the wage-worker than the man who condones mob violence in any shape or who preaches class hatred.” He identified “the rock of class hatred” as “the greatest and most dangerous rock in the course of any republic.”

Pullquote: The country saw the GOP rupture based on atmospherics, brazenly inaccurate accusations, ideological fervor and personal whims writ large. It was the politics of temper tantrum.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review