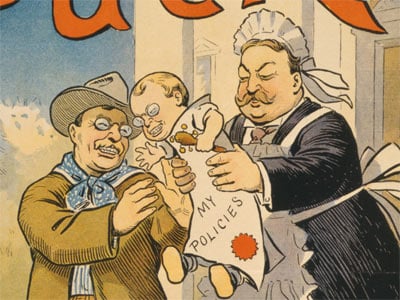

Teddy Roosevelt and Taft: The Odd Couple

Mini Teaser: Few American stories of personal fellowship are as poignant as the Roosevelt-Taft friendship—and its brutal disintegration.

Second, Roosevelt found that during the latter part of his seven-year presidency he no longer possessed the political clout to get his initiatives through Congress. He attributed this to the “lame duck” effect of his promise to the American people, when he ran for a second term, that he wouldn’t seek a third. Goodwin credits this rationale, and no doubt it contributed to his diminished political force as his White House tenure wound down. But another factor was that the country had absorbed about as much progressivism as it was prepared to handle at that time in its history, absent the kind of crisis that emerged a generation later with the Great Depression. Indeed, even Roosevelt’s distant cousin, Franklin Roosevelt, found his New Deal initiatives reaching their limit after he sought to exploit his landslide reelection victory of 1936 by “packing” the Supreme Court.

But Theodore Roosevelt, with his big domestic initiatives, had altered the political landscape of America and thus had emerged as a leader of destiny among American presidents. Accepting, based on his two-term commitment, that he must relinquish the presidency, he deftly fostered the election of Taft as his successor and then headed off to Africa for a year of big-game hunting, confident that his friend would carry on his policies. Upon his return, he thought otherwise.

THROUGHOUT THEIR friendship and intertwined careers, Roosevelt and Taft had been a powerful combination, complementing each other’s weaknesses and foibles. That was in part what each appreciated about the other. Roosevelt the impetuous, instinct-driven politician appreciated Taft’s measured, careful decision making. Taft admired Roosevelt’s ability to size up a political situation instantly and seize the initiative on it. Roosevelt wrote: “He has nothing to overcome when he meets people. I realize that I have always got to overcome a little something before I get to the heart of people. . . . I almost envy a man possessing a personality like Taft’s.” For his part, Taft often wished he could incorporate some of Roosevelt’s quick insightfulness and scintillating use of the language. “I wish I could make a good speech,” he confessed to his wife, adding that a recent performance in Michigan had left “a bad taste in my mouth.”

But once their paths diverged with Roosevelt’s trip to Africa, these differences in temperament took on an entirely new coloration. Progressives who expected Taft to carry on Roosevelt’s policies often seemed unmindful that even Roosevelt had failed to carry on his own policy preferences to the end of his presidency. Worse, the most ardent progressives seemed to want Taft to operate in TR fashion. That wasn’t possible. At one point, when President Taft shied away from taking a particular fight to the American people, as TR no doubt would have done, he said wistfully, “There is no use trying to be William Howard Taft with Roosevelt’s ways.”

Indeed, there was a halting quality to Taft’s leadership. But he pursued significant elements of the progressive agenda, ultimately with considerable success. While Roosevelt had avoided a tariff fight lest he drive a wedge through his party, Taft plunged into the fray and helped produce trade legislation that represented a significant party turnaround on the issue. Though he didn’t get as much as he wanted and radical reformers complained when he didn’t veto it, the legislation represented a significant political achievement. But then the president unwisely heralded the bill as “the best bill that the Republican party ever passed,” signaling that he had no intention of pursuing any future tariff reductions. Predictably, the radical reformers cried betrayal.

Despite such political lapses, Taft brought forth a new railroad bill that bolstered the power of the Interstate Commerce Commission to initiate action against rate hikes. He created a “special Commerce Court” to expedite judgments and brought telegraph and telephone companies under the authority of the Interstate Commerce Act. New reporting requirements for campaign contributions were enacted. Arizona and New Mexico joined the union as states. A new Bureau of Mines emerged to regulate worker safety in the mining industry. Taft also fostered the creation of a postal savings bank to provide people of limited means a safe haven for their savings. Much of this was possible because of Taft’s deft deal making during the arduous efforts to get his tariff bill through Congress, when he accepted amendments from old-guard conservatives in exchange for later support for his broader agenda.

In addition, Taft proposed legislation to enact a corporate income tax, which cleared Congress, and a constitutional amendment authorizing an individual income tax, which also cleared Congress and was sent to the states for ratification. (It was ratified in 1913.)

It’s impossible to know what drove Roosevelt to ignore all these achievements and go after his old friend, to destroy his presidency and deliver a powerful blow to his own party. But it’s difficult to escape the conclusion that the greatest factor was the former president’s outsized ego. A telling clue may be the report, mentioned by Goodwin, that Roosevelt told a friend he would cut his hand off at the wrist if he could retrieve his pledge not to run for a third term. Wisconsin senator Robert La Follette, a close Roosevelt observer, speculated that he left the White House with a prospective 1916 run for president firmly in mind. But, when he saw Taft’s weakness with GOP reform elements and tasted the nectar of his own lingering popularity, he “began to think of 1912 for himself. It was four years better than 1916.”

After all, it isn’t easy becoming an ex-president at age fifty, yielding to others the power and glory that once were so heady and thrilling in one’s own hands. For a man who wanted to be the bride at every wedding and the corpse at every funeral, it was particularly difficult to accept such a loss of position and power. In any event, while Roosevelt couldn’t win on an independent-party ticket, he could keep Taft from winning. And that paved the way for the presidency of Democrat Woodrow Wilson.

GOODWIN BELIEVES Taft’s political demise stemmed from his own limitations as president. “For all of [his] admirable qualities and intentions to codify and expand upon Roosevelt’s progressive legacy,” she writes, “he ultimately failed as a public leader, a failure that underscores the pivotal importance of the bully pulpit in presidential leadership.” Perhaps. But presidential leadership comes in many guises, and ultimately it’s about performance. Taft’s performance, based on the political sensibility he shared with Roosevelt, was exemplary. His largest burden was the split within the Republican Party spawned by Roosevelt’s own resolve to interject progressive concepts into national governance. This resolve, coupled with Roosevelt’s own increasingly rough-hewn manner of dealing with Congress, had absorbed his last stores of political capital long before the end of his presidency.

But Taft managed to wend his way through this political environment and keep the flame alive, to replenish the stores of political capital through his own deft deal making and good-natured compromising. His most dangerous adversaries turned out to be those people Roosevelt had called “fool reformers.” Then his old friend Teddy returned from Africa and joined the fool reformers. But suppose Roosevelt had taken a different tack. Suppose he had rushed to the defense of his old companion and heralded his middle-ground techniques as being firmly in the tradition of his own political ethos. Suppose that, in doing this, he had enabled Taft to arrive at a synthesis of politics that could have sustained a winning coalition and carried him through the coming election and into a second term. Then Roosevelt’s legacy would have remained secure under the Republican banner, and he would have been positioned to take ownership of the 1916 canvas, when he would have been a vigorous fifty-eight years old.

Instead, the country saw a party rupture based on atmospherics, brazenly inaccurate accusations, ideological fervor and personal whims writ large. It was the politics of temper tantrum, the product of a man whose most outrageous traits, though frequently charming, had always been potentially problematic but generally under control. Now they erupted onto the political scene with unchecked force, sweeping his old friend, his party and his country into the resulting vortex.

Robert W. Merry is the political editor of The National Interest and an author of books on American history and foreign policy.

Pullquote: The country saw the GOP rupture based on atmospherics, brazenly inaccurate accusations, ideological fervor and personal whims writ large. It was the politics of temper tantrum.Image: Essay Types: Book Review

Essay Types: Book Review