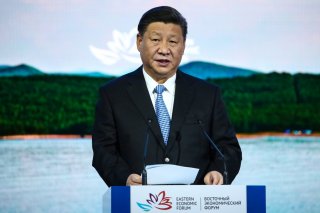

As Afghanistan Collapsed, China’s Xi Jinping Visited a Museum

Xi Jinping has created an intellectual superstructure that elevates history to the importance of ideology. History and ideology are interwoven to the point of near indistinction, and both are utilized in Chinese policymaking.

A crisis is good for many things—among them, illuminating the paradigms that guide decision-making. In the afterward of Niall Ferguson’s masterful Ascent of Money, he recounts how, in the worst days of the 2008 financial crisis, Ben Bernanke’s Federal Reserve decided to ditch its econometric models that had consistently minimized the threat of such an acute crisis and instead chose to apply its understanding of the history of America’s prior financial cataclysm, the Great Depression.

The collapse of Afghanistan, and the ensuing regional crisis, has inspired a similar occasion for historicizing in China. It has also provided a real-time look at how historical analogy qualifies as a core analytical activity in Xi Jinping’s China.

Despite the insistence of brash editors at China’s Global Times, the collapse of Afghanistan came as a shock and triggered alarm. It immediately ushered in “ferocious debates” in China about the direction of Beijing’s Afghan strategy—and inspired a multitude of prescriptions. Zhuo Bo, a retired People’s Liberation Army colonel, suggested in the New York Times that China should fill the United States’ void and adopt a more hands-on presence in Afghanistan. Mei Xinyu, a notable economist within China’s Ministry of Commerce, encouraged caution.

A range of recommended steps—from Zhou’s investment campaign to Mei’s entreaty to watch the forty-seven-mile Chinese-Afghan border carefully—followed. The common thread unifying these official and semi-official Chinese reactions to Afghanistan’s collapse was the encouragement to act urgently and decisively.

While elements of China’s policy apparatus drew up plans of action, Xi did something different. His response was to “ideate” the problem, to contextualize and intellectualize it. His focus was on the threat that the rise of a fundamentalist Islamic regime posed to China’s majority-minority provinces. It is no coincidence that Xi almost immediately convened the first central conference on ethnic affairs in seven years. What he did next was even more telling. He ventured from Beijing to nearby Chengde on an “inspection tour” of a historical exhibition about “Ethnic Unity in the Prosperous Qing Dynasty.”

When Afghanistan collapsed, strategists talked of occupation; Xi visited a museum.

The night of Xi’s visit to Chengde, a sixteen-minute report on CCTV, China’s national evening news, described what must have been an incongruous scene: “Entering the exhibition hall, Xi stopped to look at the development of ethnic relations in the Qing Dynasty” before holding forth on “measures to safeguard ethnic unity, border stability and national unity.” The message state TV took away from Xi’s visit to the museum was an erudite one—to “better summarize historical experience, reveal historical laws and grasp historical trends.” In other words, if the diagnosis was spillover unrest from Afghanistan, the prescription was a careful application of the history of early modern Chinese ethnic relations.

At first glance, the episode is bizarre. Often, it is moments of incongruence that most illuminate otherwise inscrutable policy actions. Anthropologists, for example, have persuasively argued that the best points of entry for grasping a foreign system can be the areas where it appears most opaque.

Xi’s immediate appeal to Chinese history in response to Afghan chaos matches a pattern I have noticed over my eighteen months tracking the historical analogies embedded in China’s key strategic documents. When a crisis hits—whether it be terrorism in Xinjiang, Donald Trump’s tariffs, or Afghanistan’s fall—Xi and his advisors turn to a historical memory bank populated by analogies like the Soviet Union’s experience or China’s own experience during the Century of Humiliation.

This summer, a remarkable, understudied Q&A series with Xi in the People’s Daily, the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) flagship newspaper, reinforced Xi’s directive to adhere to the lessons of history. The twenty serialized reports compiled Xi’s internal speeches—some dating internally to December 2013, nine months into Xi’s first term, while others are modifications of more recent material, previously published in Xi’s Governance of China.

Xi has linked the retention of history and a rejection of “historical nihilism” directly to the CCP’s survival. One particular piece in the Q&A series elaborates on Xi’s commitment to historical analogy. “General Secretary Xi Jinping has paid attention to grasping the laws of history and development trends from the prisms of history, reality and the future, thinking about the future destiny of the Chinese nation… demonstrating a political vision and historical thinking of ‘thinking a thousand years and seeing a thousand miles.’”

Talking about the Soviet Union is one way Xi emphasizes the importance of history in CCP policymaking. In the same Q&A series, Xi identifies the Soviet Union’s decision to “remove from its Constitution Article 6” as “one of the major reasons for the collapse of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union”; praises a short-lived and little-known regional Chinese Soviet Republic in Ruijin, during China’s twentieth-century republican period; cites an ancient Chinese proverb (“if you destroy the country of people, you must go to its history first”); and alludes to a thousand-year-old Tang dynasty poet—all in service of one central tragedy: “Once upon a time, how powerful was the Communist Party of the Soviet Union?... Now it has become a painful memory.”

No other leader of note would integrate the ancient Chinese past, ancient Chinese proverbs, and ancient Chinese poetry so thoroughly in the everyday policy work of crisis management. Xi’s method as an applied historian has been his relentless effort to make history an actionable, emergency management technique.

Christopher Vassallo is a former Schwarzman Scholar and researcher at the Asia Society Policy Institute and Harvard’s Belfer Center. He graduated magna cum laude from Harvard with a degree in history. His Twitter handle is @VassalloCMV.

Image: Reuters.