How Middle Eastern Missiles Transformed Israel’s Security

By turning toward the use of missiles, Israel’s adversaries changed the balance of power in conflicts with Israel as well as their outcomes.

Since its establishment, Israel has relied on a security doctrine predicated on a major qualitative military edge and excellent intelligence capabilities, enabling it to wage fast and decisive wars outside its own territories. This strategy was displayed during the 1967 Arab-Israeli War, in which Israel inflicted a resounding defeat on Egypt, Syria, and Jordan. Ever since, Israel has managed to maintain a qualitative military edge and a favorable regional balance of power in its confrontation with its Arab neighbors.

Israel's old security doctrine was determined by a number of factors that accompanied stem from its establishment and history: Israel’s hostile environment and neighbors, its lack of strategic depth, and the Arab states’ significantly larger populations. Although these factors theoretically have not changed, and Israel continues to possess the main capabilities making this doctrine sustainable, Israel’s security doctrine—which defines its military strategy—has gradually changed.

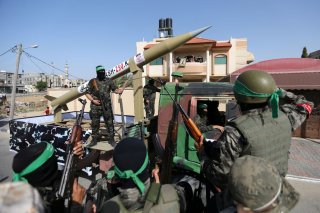

By turning toward the use of missiles, Israel’s adversaries changed the balance of power in conflicts with Israel as well as their outcomes. Despite their accuracy and destructive capabilities, missiles are relatively inexpensive, difficult of trace, and easy to obtain or manufacture. It has now become difficult to achieve a decisive win with a knockout blow, and Israel’s wars no longer take place far from its highly populated areas. The October War of 1973 between Israel and Egypt, which was the first war in which Israel faced a serious threat from an enemy’s missile arsenal, did not end with Israel achieving victory by a knockout as it had in the past.

Therefore, Israel had to develop new political and security strategies that adapted to the developments of the October War and aligned with its political doctrine that focused on managing the conflict with the Palestinians, Lebanese, and Syrians. Politically, Israel chose to neutralize the security threats posed by its neighbors after the 1973 war by either solving conflicts through peace agreements, in which Israel returned occupied lands, or by managing the conflicts through truces and negotiations where it continued to occupy territory.

After beginning a phased withdrawal from the Sinai Peninsula in 1974, Israel signed the Camp David Accords in 1978 and a peace treaty with Egypt six months later, thus neutralizing the threat posed by Egypt. Before that, in 1970, Israel froze hostilities with Jordan following King Hussein’s successful effort to push Palestinian forces from the country. Mutual security arrangements between Israel and Jordan provided Israel with security and stability on its western border and their relationship was solidified in an Israeli-Jordanian peace agreement signed in 1994. With Israel continuing to control much of the Golan Heights in the wake of the 1967 war, it succeeded, with U.S mediation, in signing a disengagement agreement with Syria in 1974. This arrangement has provided Israel with security on the Syrian front for many years.

In contrast to the relatively peaceful relationships that Israel now has with most of its neighbors, Israel’s two-decade-long occupation of southern Lebanon and the establishment of Hezbollah in the 1970s has kept the Lebanese front open until today. Although Israel signed the Oslo Accords with the Palestinian Liberation Organization in 1993, its strategy continues to be a cycle of conflict management as it expands settlements and neutralizes opposition in the West Bank. However, a new front opened in the Gaza Strip following the Israeli withdrawal in 2005 and Hamas’ subsequent takeover of the Strip in 2007. In addition, the Syrian front reopened after the outbreak of the Syrian revolution and Iran’s intervention aimed at supporting the Assad regime and countering the multifaceted international intervention in Syria.

By creating a long-term and wide-ranging threat to the Israeli domestic front, Hamas and Hezbollah’s missile arsenals have become an important deterrent weapon. Unaccustomed to such threats, Israel’s questionable ability to endure the threat posed by the missile arsenals has weakened deterrence. This explains the calculated state of escalation that Hamas and Hezbollah resort to as well as the restraint adopted by Israel. Since a ground war would be incredibly costly and airstrikes cannot fully eliminate these arsenals, Israel cannot achieve a decisive win by destroying Hamas and Hezbollah’s military infrastructure and missiles. In the light of the difficulties, dangers, and political costs of fighting a long-term war, a ground battle with either movement would in no way be a guaranteed success.

Having carried out negotiations with Hezbollah since 2013 and with Hamas following the 2009 and 2021 conflicts, Israel continues to rely on a strategy of compromises and armistices to guarantee temporary settlements with specific rules of engagement dictated by the existing circumstances. This balance has governed Israel's retaliatory and preemptive operations in Gaza and Lebanon. While Israeli operations typically avoid escalation into major conflicts, limited Israeli raids ended with the Second Lebanon War as well as large-scale conflicts in Gaza.

Israel has adopted a new security strategy in response to the reopening of the Syrian front. This strategy aims to use preemptive strikes to prevent Syria from establishing a strengthened military infrastructure while delaying any outbreak of large-scale wars. Following the reopening of the Syrian front in 2015, the Israeli army published an explanation of its new security doctrine, introducing the term “the campaign between wars,” which means preemptive strikes. Preemptive strikes are not new to the Israeli security doctrine, as they were used frequently against Palestinian targets under the pretext of Palestinian “intentions to launch an attack” against Israel. However, Israel now uses preemptive strikes to target Iran and its allies in the region, focusing on the Syrian front and targeting specific military objectives while attempting to avoid civilian targets.

Last August, the latest clash between Hezbollah and Israel on the Lebanese border came within the framework of Israel's attempts to change the rules of engagement with Hezbollah by taking advantage of the complex political and economic conditions in Lebanon. In response to the firing of missiles at Israel, Israel launched an air attack for the first time since 2013. However, Hezbollah undermined Israel's attempt by launching nineteen missiles at Israel and maintaining the balance of deterrence between the two sides on the Lebanese front. Reflecting the two sides' unwillingness to turn retaliatory operations into a wide war, both Israel and Hezbollah avoided inflicting massive human or material damage on the other.

Now we can understand Hassan Nasrallah’s, Hezbollah’s secretary-general, announcement that an Iranian fuel vessel was headed to Lebanon. After seeing Iran providing oil to Syria, Hezbollah aims to gain access to Iranian oil as well. This is not the first time that Hezbollah has tried to change the rules of engagement with Israel. Hezbollah attempted to change them in early September 2019, when it announced the destruction of an Israeli military vehicle on the opposite side of the Lebanese border in response to the killing of two of its members in a raid near Damascus. Hezbollah's response was not typical, as the party has not traditionally responded to Israeli attacks outside of Lebanon and away from the Lebanese front.

The limits of the rules of engagement between Israel and Hamas are determined in the context of the mutual attacks inside Gaza and the Gaza envelope. Hamas attempted to change those rules of engagement last May when it threatened to trigger a new round of conflict following an Israeli attack on the Al-Aqsa Mosque in Jerusalem. Israeli pressure on Hamas in the wake of the recent war, which is similar to that applied in the past, has not gone beyond this calculated framework. By imposing restrictions on Hamas within Gaza but also providing the group with access to international aid, Israel is attempting to gain the greatest possible benefits within the framework of the bargaining processes between Hamas and Egypt. On the other hand, and within the framework of the balance of deterrence, Hamas is making a calculated escalation to improve the terms of the truce after Egypt’s failed efforts to mediate an armistice that improves the conditions of life in Gaza. Although the Israeli and Palestinian sides affirmed their unwillingness to slip into a new round of war, another large-scale war remains very possible, particularly after the recent escape of Palestinian prisoners.

Dr. Sania El-Husseini is a Professor of Political Science and International Relations in Ramallah, Palestine.

Image: Reuters.