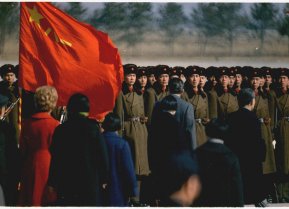

A Russian-Chinese Partnership Against America?

China and Russia consider themselves great powers, and there is agreement in both Beijing and Moscow on cooperating to limit or constrain America’s ability to dominate international relations and challenge their sovereignty.

CHINA AND Russia consider themselves great powers, and there is agreement in both Beijing and Moscow on cooperating to limit or constrain America’s ability to dominate international relations and challenge their sovereignty. Moscow and Beijing are committed to multipolarity and a spheres of interest approach, where each state can regulate its periphery without U.S. interference. This close partnership will likely continue as long as Xi Jinping and Vladimir Putin remain in office, and it is probably durable enough to survive if either or both of these leaders steps down or dies. Both have arranged for their rule to continue—indefinitely in the case of Xi, and to 2036 in the case of Putin, assuming he decides to stay in office that long. Each regime is acting as a pragmatic, nationalist great power, and each sees its interests as far more compatible with the other power than with the United States.

Russian and Chinese adherence to global rules is selective and cynical, though international law and institutions can be manipulated to frustrate American foreign policy goals. The two often vote together in the United Nations, for example, using their veto to counter U.S. and European Security Council resolutions on Syria. In 2018, Russian and Chinese diplomats discussed coordinating on the Middle East and agreed to maintain a dialogue on a range of issues in the region. The Middle East presents opportunities and security concerns for Russia and China as the United States disengages. Both opposed Donald Trump’s withdrawal from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action and have taken advantage of the situation by negotiating closer military and economic cooperation with Tehran. More broadly in the Middle East, China became the region’s largest investor in 2016, and in the following year established its first overseas base in Djibouti. Russia is engaged diplomatically across the region; is selling weapons to Egypt, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Libya, the UAE, and Turkey; and recently concluded a twenty-five-year agreement for a naval base in Sudan to complement its base at Tartus, in Syria.

In other regions, the two countries may not be cooperating openly, but their implied support for each other’s aggression narrows Washington’s policy options. Beijing has refrained from criticizing Moscow over the annexation of Crimea and violating Ukraine’s sovereignty, for example, while Moscow implicitly supports China’s growing presence in the South China Sea. China, with its large investments and trade interests, has far more leverage on the African continent than Russia, which is limited largely to providing weapons and mercenaries, the latter through Yevgeny Prigozhin’s Wagner group. Moscow and Beijing may not be actively strategizing together, yet the two are filling a vacuum resulting from American neglect. Similarly, in Latin America, each is pursuing a separate agenda, with Russia selling arms and concluding energy deals while China imports commodities, invests in infrastructure, and promotes cultural and educational exchanges. Both support independent-minded governments—in Venezuela, Cuba, and Nicaragua—and seek to erode American influence in the hemisphere.

Russia’s “return” to South Asia, especially the renewed emphasis on India and new developments with Pakistan, has the potential to increase tensions with Beijing. Moscow continues to promote the idea of a Russia-China-India triangle, the brainchild of former Foreign Minister Yevgeny Primakov—to counterbalance the United States and its alliances. To this effect, Russia attempted to broker an agreement between India and China over tensions along the Actual Line of Control on the sidelines of the 2020 Shanghai Cooperation Organization meeting in Moscow. Russia’s goal may be to enmesh China in a web of agreements and institutions that would constrain its efforts at establishing hegemony in South and Central Asia. However, Russia is contending with the United States and its Indo-Pacific strategy for influence in New Delhi and has been selling high-tech weaponry to India to strengthen the bilateral relationship. In addition, Russia is building political and trade ties with Southeast Asia, hedging against excessive reliance on China.

A rising China will likely challenge the United States for global hegemony, which could result in armed conflict. If this occurs, it is unlikely that Russia would back China militarily. It is even less likely that China would actively support Russia in the event of a conflict in Europe. Should conflict break out in one region, though, Washington would be hard-pressed to deal effectively with a crisis in the second. A key strength for the United States, however, is its network of alliances in Europe and the Pacific; neither Russia nor China can match the United States on this power dimension. If the United States continues to neglect or alienate its allies it will seriously degrade America’s ability to respond to challenges from Russia or China in their respective regions. In a clear departure from Trump’s America First approach, the Biden administration has announced plans to restore close relations with traditional American allies in Europe and Asia.

Under President Trump, U.S. leadership of the liberal international order eroded dramatically. China has benefited more from these postwar economic arrangements than has Russia, and Beijing seeks merely to modify such institutions as the IMF and World Bank to suit China’s long-term interests. By contrast, Russian leaders believe the current international order is used by Washington to keep Russia weak. Both countries reject the political dimension of the liberal international order that favors human rights, humanitarian intervention, and democracy promotion. Beijing seeks modification of the international order on its terms; Russia frequently engages in disruption to weaken the United States. While a Biden presidency may reinvigorate American support for liberal internationalism, the global rise of populism and nationalism indicates the zeitgeist may be slipping toward a more authoritarian and statist model of governance.

CHINA IS adept at economic statecraft, far more so than the United States, and is using its position as the leading economic power (measured in purchasing power parity) to undercut American influence globally. The massive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is central to this effort. Through BRI, Beijing can leverage trade, investment, and infrastructure development supplemented by modest increases in soft power to challenge America’s post-Cold War dominance. Russia plays a small but significant role in this strategy.

The Russian-Chinese economic relationship has expanded in recent years and will likely continue to grow modestly. In 2019, bilateral trade was over $110 billion, although trade declined in 2020 as a result of overall slowdowns from COVID-19 restrictions. There are distinct complementarities in the relationship: Russia exports oil, natural gas, other raw materials, and weapons to China, while China exports mostly finished goods to Russia. This trade structure is not likely to change much in the near future. And Russia is far more dependent economically on China than the reverse; in 2018 China accounted for 15.5 percent of Russia’s total trade turnover, while Russia accounted for just 0.8 percent of China’s.

The network of oil and gas pipelines constructed over the past decade will link the countries’ economies for the next thirty years, creating a web of interdependence. According to the Energy Information Administration, China’s demand for petroleum will continue to grow over the next five years, as will demand for less-polluting natural gas. The Power of Siberia natural gas pipeline, in operation since December 2019, and a planned second parallel line will more than double the capacity of Russian gas exports to China. However, the importance of the energy relationship should not be overstated. Chinese crude oil imports are fairly diversified—in 2019 only 15 percent of China’s oil imports came from Russia, second to Saudi Arabia (at 16 percent)—and China produces fully one-third of its petroleum needs domestically. Oil imports from Russia account for just under two percent of China’s total primary energy consumption, and China has eighty days of supply stored in its strategic petroleum reserve. Natural gas supplies are also quite diversified, with rising domestic production and a range of import partners.

Moscow hopes to benefit from China’s Belt and Road Initiative by serving as a transportation corridor or land bridge between Europe and Asia. In 2015, Putin and Xi agreed to a partnership between BRI and Russia’s Eurasian Economic Community, but little progress has been made to date. Chinese firms have declined almost all Russian proposals for cooperation on projects, and Moscow understands that BRI may not always serve Russian interests. But Moscow welcomes Chinese investment in Eurasia while pursuing a more diversified economic policy in the Asia-Pacific.

One key development will be the growth of Arctic trade as climate change facilitates greater use of the Northern Sea Route. China seeks to expand shipping routes through the Arctic, and Russia has the icebreakers to keep the sea lanes open for Chinese ships. But tensions exist—Moscow resents Chinese claims to be a “near Arctic” state and prefers to be the dominant power in the Arctic, which is seen as the main resource base for future economic growth. In the Russian Far East, the two countries have finalized their borders and are cooperating on major oil and gas projects, yet Chinese nationalists still resent the “unequal treaties” of the mid-nineteenth century that ceded “Outer Manchuria” to Russia, evident in the negative social media reaction to Vladivostok’s 160th-anniversary celebrations.

Beijing and Moscow are critical of U.S. dollar dominance in the global economy and are increasingly trading goods via barter arrangements or using national currencies. The U.S. dollar still accounts for 80 percent of all global transactions, but in 2019 only 51 percent of Sino-Russian trade was in U.S. dollars; this declined to 46 percent in the first quarter of 2020. Chinese trade and the renminbi are becoming increasingly important for Russian firms that since 2014 have sought to avoid U.S. sanctions and the possibility of being excluded from the swift financial messaging service.

Possible sources of tension in Russian-Chinese economic relations include China’s increasing presence in Central Asia, Russian arms sales to India, Chinese trade and investments in Belarus, and Beijing’s growing engagement with Mongolia through the China-Mongolia-Russia-Economic Corridor. For the past two years, Beijing has pressured Hanoi to shut down an offshore oil project between PetroVietnam and Rosneft, claiming at least one of Vietnam’s exploration blocks fell within China’s Nine-Dash Line. Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi reportedly asked Russian foreign minister Sergey Lavrov to lean on Rosneft to abandon the project, but his Russian counterpart declined. So far, however, the two countries have avoided clashing openly.

U.S. SANCTIONS and confrontational posturing have encouraged defense cooperation, including arms sales (China is the second-largest purchaser of Russian weapons), regular joint military exercises, and naval maneuvers. However, arms sales as a proportion of total bilateral trade have declined dramatically since the 1990s. Military exercises are an important component of the relationship but are more likely to signal support for each other’s sovereignty, security, and regional territorial disputes than serve as rehearsals for future joint operations. Moscow and Beijing jointly oppose U.S. anti-ballistic missile systems deployments in Eastern Europe and East Asia and are increasingly challenging America’s freedom of navigation (FON), with the result that the U.S. Navy dramatically ramped up its FON operations in 2019.

Russia and China understand and accept the need of the other to exercise regional hegemony in areas critical to their national security—for Russia, this is the post-Soviet space along its western and southern borders; for China, the western Pacific (especially Taiwan and Hong Kong). Both countries have security interests in Central Asia, and while Moscow and Beijing have worked together through the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, their interests are not fully harmonious in this region. Tensions could rise here as China augments its economic and military posture in the region.

Russia and China do not have a formal defense treaty, and it seems unlikely they will conclude one in the near future. Each wants to keep options open and not be dragged into a conflict that is not in their national interest. Still, at the 2020 Valdai Discussion Club, Putin stated that while Russia was satisfied with the current state of relations a formal military alliance with China could be imagined in the future. Even without a formal alliance, the two countries tout a close partnership that involves expanding trade, arms sales, regular military exercises, intelligence sharing, and sharing military technologies.

Russia does not have the military capability to challenge the United States in the Indo-Pacific, and the same can be said of China in Europe. However, each regards the United States as their chief competitor, and their relationship is described as a “strategic partnership” meant to balance American military power. This constrains U.S. operations in Eastern Europe and the Western Pacific, even if Moscow and Beijing do not formally coordinate their actions. As Hal Brands and Evan Montgomery point out, the United States is ill-prepared for opportunistic aggression—having to deal with regional challenges from both powers simultaneously. These conflicts could involve military force, but in the current environment, some form of hybrid action is more likely. The Sino-Russian partnership may not be a full-blown military alliance, but it is a de facto non-aggression pact that ensures China faces no land threat, and so is free to be more assertive along its periphery and at sea. Similarly, should a conflict break out between China and the United States in the South China Sea or over Taiwan, Russia might take advantage of the opportunity to destabilize Poland or the Baltic states. These scenarios may not be likely, but they are within the realm of possibility if we consider the relatively low costs of information or “hybrid” forms of aggression, coercive diplomacy, or obstructionism in the un Security Council.

AS IN trade, Russia and China have certain complementarities in technology. Key joint projects are planned in aviation and aerospace, nuclear reactors, drone technologies, communications, artificial intelligence, and supercomputers. Putin has revealed that Russia is helping China develop an anti-missile early warning system, while Lavrov has stated that in contrast to the United States, Russia will cooperate with China and Huawei to introduce 5G technology in Russia. Reportedly, Huawei is planning to quadruple research and development personnel in Russia over the next five years and anticipates working with Russian universities, research institutes, and the broader scientific community on artificial intelligence, information, and communication technologies. Huawei is also planning to invest up to $800 million in developing Russia’s digital infrastructure over the next five years. Many of these technologies are dual-use, with both civilian and military applications.

China’s technologies are cutting edge and cheaper than those developed in the West, making them attractive to Russian businesses and government agencies. U.S. and European “smart sanctions” that target Russian energy and military sectors provide additional incentives for Russian-Chinese cooperation in the high-tech field. However, the Kremlin has developed an ambitious domestic program for developing scientific research in mathematics, climate science, genomics, and robotics. Russia currently spends only 1 percent of its GDP on research and development, well behind other high-tech leaders like South Korea, Germany, Japan, and the United States, and only half of China’s allocation. Cooperation with China may help Russia improve its record in scientific research, but national pride—and strategic considerations—militate against excessive reliance on Chinese technology.

China and Russia agree on the need for cyber sovereignty and promote the concept within the United Nations; they reject the concept of internet freedom as promoted by the United States. The two authoritarian states are cooperating in developing technologies such as facial recognition software and internet blocking tools that improve the state’s ability to censor and control information, monitor dissidence, and repress individual freedom, and both supply surveillance gear to countries around the world. However, some tensions are apparent in technological cooperation. In August 2020, for example, a leading Russian Arctic scientist was charged with supplying classified information on submarine detection to Chinese intelligence services. Moreover, Russia and China appear willing to cooperate on cyber defense, but they do not appear to be coordinating their efforts offensively. In short, Russia and China will likely continue to cooperate on technology, but as with trade and economics, Russia occupies the junior position in the relationship.

SINGAPORE’S MASTER statesman Lee Kwan Yew once observed that as China rose, a stable balance of power in the Asia-Pacific would depend on America and Japan maintaining an isosceles triangle, where U.S.-Japanese ties remained closer than either Sino-Japanese or Sino-American relations. Today, a version of 1970s triangular diplomacy has returned; this time, Russia and China are far closer to each other than to the United States. This relationship, however, is not equilateral, but rather a “skinny” isosceles triangle with Russia as the very narrow base.

America no longer occupies the swing position in the power triangle as it did in the 1970s and 1980s. Moscow may eventually decide that it needs to align with the United States to balance a much stronger China, but that is not likely in the foreseeable future. Russia and China have many common interests, and the areas where their interests clash are few and manageable. The strategic partnership is not likely to weaken over the next few years, and may well strengthen, though it probably will not result in a full-blown military alliance. Russian-Chinese trade will likely increase over the next five years, albeit gradually, and we can expect China to ramp up investments in key areas. Energy will remain central but diminish as a share of bilateral trade. Neither Russia nor China is about to reverse course and fully buy into a liberal international order under U.S. leadership, assuming a post-Trump America attempts to reestablish global hegemony.

The Sino-Russian relationship is asymmetric, but for now, that does not appear to be a problem. Russian leaders understand their country’s junior position in the partnership, and they will strive to keep the relationship on an equal footing, though this may become increasingly difficult. For now, Beijing is careful to treat Russia with respect as a fully co-equal partner, but that could change as China becomes more confident of its global position.

The United States has benefited from having shaped the postwar international order, and its leading position has served the country well over the past seven decades. Abandoning globalization and major international institutions in favor of an isolationist position will merely put the United States at a further disadvantage vis-à-vis China and Russia. U.S. resources have been stretched thin by COVID-19, and the political dysfunction in Washington combined with deep divisions in America’s political culture have eroded the country’s post-Cold War hegemony.

Competing with Russia and China requires a careful evaluation of U.S. obligations around the world. Not all Russian or Chinese actions—in Africa or Latin America, or with the Belt and Road Initiative, for example—are harmful to U.S. interests. The argument that Washington needs to conduct a more restrained foreign policy in place of liberal interventionism should be accorded the serious attention it deserves.

The United States should cooperate with both countries where feasible, but any wedge strategy like that pursued during the Richard Nixon era is unlikely to succeed. Instead, Washington needs a more nuanced and subtle strategy of engaging bilaterally where possible, pursuing more effective diplomacy, cultivating allies, and prioritizing arenas of competition. The United States should push back against malign behavior, whether in the form of violating territorial sovereignty, cyberaggression, flouting international norms, or unfair trade practices. It may take some effort to find common ground, but there are serious global threats that demand collective action—dealing with pandemics, addressing climate change, securing reductions in nuclear arms, and combatting terrorism. We should also seek cooperative trade agreements with both Russia and China and avoid confrontational posturing that merely heightens tensions to no good end. Skilled diplomacy can reduce the risk of military conflict, yet the State Department lacks the resources it needs for effective bargaining. Finally, scientific and educational exchanges with Russia and China should be preserved and expanded.

Russia and China are convinced the United States is in decline. Admittedly America’s domestic politics are dysfunctional, its political culture deeply divided, and its economic system highly inegalitarian. The Trump administration’s America First policy undermined U.S. standing internationally by neglecting diplomacy and unnecessarily antagonizing allies and partners. The United States has more and better allies than either China or Russia, and this source of strength should be cultivated in both Europe and the Indo-Pacific. Washington also needs to restore American soft power damaged by a year of racial unrest, inept governance, partisan bickering, and domestic extremism. Russia and China are highly skilled at traditional diplomacy and disinformation but are fairly weak on most dimensions of genuine soft power. The United States may not be able to change Russian or Chinese behavior or undermine their strategic partnership, but restoring some degree of consensus and effective governance in Washington—in short, real leadership—will better position the country to deal with the Sino-Russian challenge.

Charles E. Ziegler is Professor of Political Science and University Scholar at the University of Louisville, and faculty director for the Grawemeyer Award for Ideas Improving World Order. He is the author or editor of five books and over 120 articles on various aspects of Russian and Eurasian politics and foreign policy. He has also served as the Executive Director of the Louisville Committee on Foreign Relations since 1990.