An 'Old' Battleship Actually Sank an Aircraft Carrier in 1940

This is what happenned.

At 4 p.m. on June 8, 1940, the aircraft carrier HMS Glorious was cruising west across the Norwegian Sea towards the British naval base of Scapa Flow when her lookout spotted two grey blips over a dozen miles away on the horizon.

The Glorious and her two escorting destroyers did not yet have radar, so Capt. D’Oyly-Hughes ordered the destroyer Ardent to turn about and visually investigate the sighting, while nonchalantly maintaining his westward course at cruising speed.

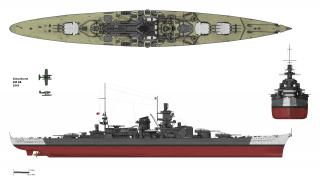

In a matter of minutes, the British sailors would discover to their horror that the innocuous little dots constituted the worst threat conceivable—the German battlecruisers Gneisenau and Scharnhorst. Only a few dozen would survive one of the most controversial naval battles of World War II—perhaps the only time battleships single handedly took out an aircraft carrier.

The prevailing narrative of naval warfare in World War II concerns how the carrier decisively unseated the battleship as the dominant naval weapon system. Yes, battleships mounted over a dozen guns that could pot huge shells at other vessels from over a dozen miles away. But a carrier could deploy over a hundred airplanes that could strike targets hundreds of miles away with torpedoes and bombs.

Just as importantly, in an era where radar technology was in its infancy, airplanes were the most effective tool for scouting out vast swathes of the ocean to locate enemy fleets.

These advantages meant that battleships and battlecruisers were repeatedly sunk by carrier-based aircraft, from Pearl Harbor to Taranto to the Battle of the Philippines Sea. In return, battleships almost never succeeded in closing into gun-range of carriers.

The Glorious was one of the first flat-top aircraft carriers ever built, converted from a speedy Courageous-class battlecruiser in 1924. Her pointed bow still poked from below a raised flight deck. Her class’s lead ship, the Courageous, had launched the first carrier-launched naval air strike in history near the end of World War I.

The 224-meter long vessel still could only carry a smaller air group of forty-eight aircraft compared to larger U.S. fleet carriers. In 1940, these included Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers, Gloster Sea Gladiator fighters, as well monoplane Blackburn Skua monoplane bomber/fighters.

The Glorious first saw action in World War II providing air cover for the Allied expeditionary force seeking to support Norway’s resistance to Nazi invasion in April 1940, her Sea Gladiators shooting down several German bombers. Her captain, Guy D’Oyly Hughes, a decorated submariner in World War I, also ordered her Swordfishes to launch raids on land targets, but air group leader J.B. Heath refused, arguing they lacked clear targets and that the pokey biplanes would be shot to pieces by flak. D’Oyly kicked Heath off the ship and departed on missions to ferry Royal Air Force Gladiators and Hurricanes to Norway.

However, in May 24, the Allies began evacuating forces in Norway due to Germany’s successful offensives into the Low Countries and France. The Glorious then was assigned to pick up the fighters she had just dropped off. The RAF Hurricanes of No.46 squadron were relatively fast and lacked arrestor hooks—but by tying on sandbags, the pilots managed to weigh their tails down and pull off short carrier landings. This feat accomplished, the Glorious was to sail back to the UK with fellow carrier Ark Royal for mutual protection.

However, on June 8 D’Oyly-Hughes received permission to depart independently for Scapa Flow escorted by just two destroyers. Officially, the Royal Navy maintains this was to save fuel. However, crew members have alleged D’Oyly-Hughes was in a hurry to attend Heath’s court martial.

In any event, none of the Glorious’ aircraft were airborne performing a Combat Air Patrol, nor were any readied on the flight deck—perhaps due to concerns of pilot fatigue. The carrier’s tall crow’s nest was unoccupied; and only twelve of her eighteen boilers were kept active, limiting her speed.

These decisions proved fatal, as that same day, the German Kriegsmarine dispatched surface forces including the battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau on Operation Juno, a sortie redirected to interdict Allied evacuation ships.

Earlier that day the battlecruisers sank an oil tanker and a trawler. At 3:45 p.m., crew on the German capital ships spotted the funnel smoke of the British warships and surged forward to close the distance. While the British sighted the ships fifteen minutes later, Captain D’Oyly didn’t call action stations and begin having Swordfish bombers lifted to the flight deck until 4:20 p.m..

Crucially, the German battlecruisers were fast—but Glorious could nearly match their speed at thirty knots, once her boilers built up enough steam.

Just seven minutes later, the Scharnhorst opened fire on the investigating Ardent, busting open a boiler. The much smaller vessel immediately laid a smoke screen which it used as cover to launch hit-and-run torpedo attacks. The destroyers’ 4.7” lacked the range and penetrating power to threaten the German battlecruisers—but their torpedoes could cause devastating damage if they could land a hit.

While her smaller 15-centimeter cannons exchanged shots with the Ardent, Scharnhorst’s big 11” turrets blazed away at the distant flat-top. Five minutes later, in one of the longest-range hits in naval history, the Scharnhorst’s third volley screamed over fifteen miles to slam straight into the Glorious’s flight deck, blasting open a huge hole that rendered it unusable and knocking two Swordfish bombers into the water. Splinters also pierced one of the carrier’s boilers, slowing her down.

By then Glorious had transmitted a distress message which was picked up by the heavy cruiser HMS Devonshire thirty to fifty miles away. Though the Royal Navy claimed the transmission was too garbled to be understood, her crew later testified to the contrary. In fact, the Northampton was secretly evacuating the Norweigian royal family to the UK, and commanding Vice Admiral John Cunningham had strict orders to maintain radio silence, and thus neither intervened nor relayed the message.

At 5 PM a shell slammed into the Glorious’s bridge, killing D’Oyly and most of the command crew. Ardent was finally caught darting out for another torpedo run and set ablaze by repeated hits. She managed to complete a seventh and final torpedo run before capsizing twenty-five minutes later. By then the crippled Glorious was listing and turning in circles while being relentlessly pounded by German guns.

Rather than disengage from the hopeless fight, the Acasta peeled off from the Glorious and valiantly charged the Gneisenau. The 1,300-ton ship sustained a multiple hits from the two 40,000-ton battlecruisers—but on her second run, one of her torpedoes slammed into the Scharnhorst, ripping a 12-meter wide hole into her hull that let in over two thousand tons of water, knocked her aft “Caesar” turret out of action, killed forty-eight crew, and disabled her starboard propeller shaft.

But the battlecruisers’ retaliatory fire was devastating, and the Acasta’s blazing wrecked dipped stern-first into the water after 6 p.m. By then, the starboard-listing Glorious had also sunk. A camera crew onboard the Scharnhorst filmed the engagement, and the Glorious’s sinking, which you can see here.

The German battlecruisers then hastily left the scene without picking up survivors. Scharnhorst limped home, listing at five degrees, and would spend the next six months in Trondheim, Norway undergoing repairs. The Royal Navy apparently remained unaware of the battle and made no rescue effort, only learning what happened after Germany announced the victory.

Only one crew member from the Ardent, two from the Acasta, and thirty-six from the Glorious survived to be picked up by Norwegian and German forces. 1,596 Royal Navy and Air Force personnel died, many freezing to death awaiting rescue.

Only extraordinary circumstances—particularly the lack of Combat Air Patrol—made the ambush of the Glorious possible by two large capital ships on a clear day. For decades, the Royal Navy offered a vaguely exculpatory account of the disaster, but in the 1980s historian Stephen Roskill published an article holding poor command culture by Captain D’Oylyy responsible for the tragedy. The unusual disaster continues to evoke controversy, and even questioning in Parliament, decades later.

Battleships accompanied by other surface warships did directly engage carriers one more time in World War II during the Battle of Samar, though this time the U.S. carriers’ air wings participated in the fight leading to a very different, though no less dramatic outcome.

Sébastien Roblin holds a master’s degree in conflict resolution from Georgetown University and served as a university instructor for the Peace Corps in China. He has also worked in education, editing, and refugee resettlement in France and the United States. He currently writes on security and military history for War Is Boring.

Image: Wikimedia Commons