World War III (Almost): China, Russia, South Korea and Japan Nearly Went to War

What stopped this disaster?

Aerial encounters between bombers and patrol planes and jet fighters are common, though sometimes tense occurrences as fighter pilots sometimes seek to intimidate the crews of bombers or spy planes with close, dangerous flybys. However, it’s rare today for probing bombers or spy planes to actually violate another country’s airspace—and even rarer for fighters to open fire during an intercept, even if only in warning.

The morning dawned peacefully enough on July 22 as Chinese and Russian warplanes soared towards a rendezvous point over the Sea of Japan for what was to be their first-ever joint patrol.

As Russia’s defense ministry put it, this was intended to deepen “Russian-Chinese relations within our all-encompassing partnership, of further increasing cooperation between our armed forces, and of perfecting their capabilities to carry out joint actions, and of strengthening global strategic security.”

Representing the PLA Air Force were two H-6K jet bombers which threaded their away through the international airspace of the Korean Strait to meet over the Eastern Sea with two modernized Russian Tu-95MS “Bear” bombers, each with four turboprop engines with noisy contra-rotating propellers.

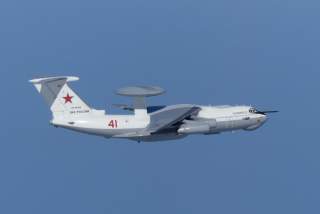

Accompanying the Bears was a Russian A-50 Mainstay airborne early warning plane with a huge rotating radar dish mounted on a dorsal pylon to helped coordinate the multinational elements.

These aircraft repeatedly entered and exited South Korea’s air-defense identification zone (ADIZ), so the South Korean air force dispatched eighteen domestically-built F-15K Slam Eagle and KF-16 jet fighters to intercept them.

Japan’s Air Self Defense Force also scrambled jet fighters which photographed the Russian A-50 plane.

Air defense identification zones often extend into international airspace (beyond twelve nautical miles from a country’s borders/shoreline) and their sanctity is not formally recognized under international law. As China, Japan and South Korea have overlapping ADIZs over the East China Sea, their “violation” is not intrinsically a grave matter. Russian and Chinese aircraft had entered Korea’s ADIZ more than three dozen times in the last seven months according to Korea’s Yonhap news agency.

But things changed when the A-50 radar plane veered sharply westward and overflew Korean airspace for three minutes over Dokdo islets 9:09 AM.

The islets are also claimed by Japan, which calls them the Takeshima islands. Washington designates them the “Liancourt Rocks” to avoid taking sides.

Earlier in December 2018, a Korean destroyer locked its fire-control radar onto a Japanese P-1 maritime patrol plane near the islands, resulting in a war of words between Seoul and Tokyo which has escalated into a deepening political rift and economic sanctions. Bear in mind the islets have a collective surface area of only forty-six acres and are populated by only fifty residents, though they do lie astride valuable fishing grounds and possible natural gas reserves.

As the A-50 cruised over the islets of contention, the South Korean jets shot eighty shells from their 20-millimeter cannons, and launched ten flares—aerial decoys ordinarily intended to divert heat-seeking missiles—to warn the unarmed radar plane to change course.

According to a Korean map, the A-50 eventually banked 90 degrees onto a southeastward trajectory—and then circled tightly around to reenter the airspace over the islets a second time on a north-eastern trajectory at 9:33 a.m. During the second, four-minute overflight, the Korean jet fighters fired 280-more cannon rounds and ten more flares.

Aerial encounters between bombers and patrol planes and jet fighters are common, though sometimes tense occurrences as fighter pilots sometimes seek to intimidate the crews of bombers or spy planes with close, dangerous flybys. However, it’s rare today for probing bombers or spy planes to actually violate another country’s airspace—and even rarer for fighters to open fire during an intercept, even if only in warning.

South Korea’s foreign ministry complained to Moscow. Not to be outdone, Tokyo then issued formal complaints to both Russia and South Korea.

Unfortunately, Korea and Russia’s own tragic history indicates that warning shots can be difficult to detect. In 1983, Korean Air Flight 007 fell wildly off course due to a combination of technical and pilot error, and found itself on a course which repeatedly violated Soviet airspace. A Soviet Su-15 interceptor finally caught up with the 747 airliner and fired two-hundred 23-millimeter cannon shells parallel to it—before the pilot acceded to orders to shoot down the Jumbo Jet with a missile, killing all 269 aboard. A Blackbox later recovered by the Soviet Union revealed the airliner’s crew were oblivious to the cannon shells sailing past them.

The July 2019 incident is also peculiar given that Seoul and Moscow have gotten along fairly well in the post-Cold War era. For example, Korea’s Ai-Missile Defense system is based in part on Russian missile technology. In 2018, Moon Jae-in became the first South Korean president to pay a state visit to Russia, and the countries’ air forces established a hotline intended to alleviate precisely such incidents as occurred this July.

Later that day, a South Korean spokesman reported that a Russian military attaché “expressed deep regret” for the incident, which he blamed on a technical glitch. But the following day, however, Russia insisted it had not made an “official apology,” while accusing two Korean KF-16 pilots of “hooliganism” performed “illegal and dangerous” maneuvers near its Tu-95 bombers. The A-50 which was reportedly shot at did not figure in the Russian statement.

On July 25, South Korean and Russian officials met in Seoul and agreed to exchange radar images and voice recordings to better ascertain what transpired on July 23.

What explains the alleged Russian airspace violation?

One possibility is a navigational error. However, it also seems distinctly possible the overflight was deliberately calculated to tweak South Korea and Japan by bringing the disputed islands back into the news.

David Cenicotti at The Aviationist also points out the A-50 is a capable radar- and electromagnetic surveillance platform, and that Russia may have been using it to study the reaction time and sensor signature of Japanese and South Korean jets.

The joint Russian-Chinese bomber patrol is also significant as a symbolic statement of shared purpose between Moscow and Beijing, though the two Asian powers remain far from being in a true military alliance. In a high-intensity conflict, H-6s and Tu-95s would be used to attempt to sink enemy warships and aircraft carriers. If such patrols become routine, that could eventually reshape the security environment in the western Pacific.

Recently, Chinese economic sanctions persuaded South Korea to promise not to deepen ties with the United States or Japan—particularly given Washington’s recent disinterest in maintaining its alliances. It remains to be seen whether incidents such as these may reverse that trend, or simply contribute to the deepening rift between South Korea and Japan.

Sébastien Roblin holds a master’s degree in conflict resolution from Georgetown University and served as a university instructor for the Peace Corps in China. He has also worked in education, editing, and refugee resettlement in France and the United States. He currently writes on security and military history for War Is Boring.

Image: Reuters.

This article first appeared in July 2019 and is being republished due to reader interest.